Taming Sodium Hydroxide for Energy Storage

Taming Sodium Hydroxide for Energy Storage

How do you keep the electricity flowing when the sun goes down? Part of the answer may be found in the stuff that unclogs your sink.

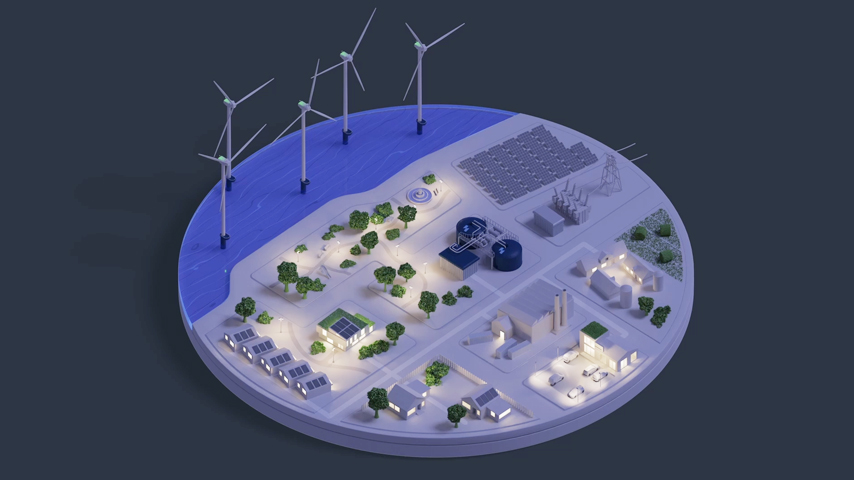

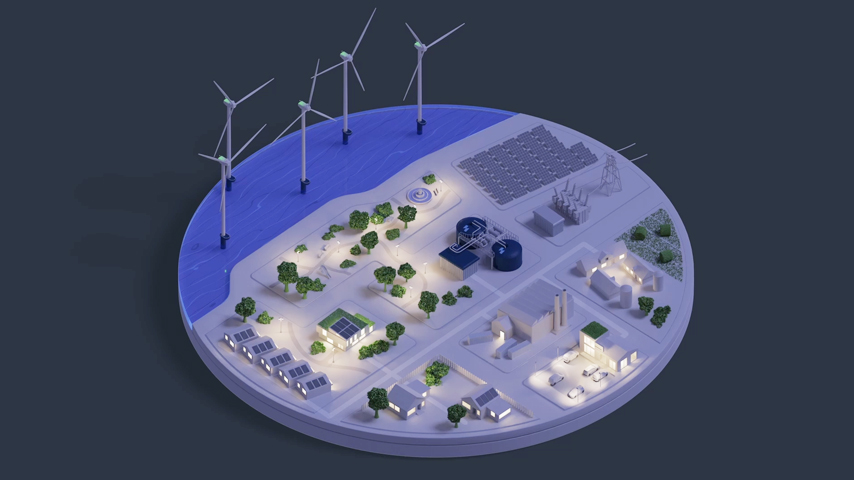

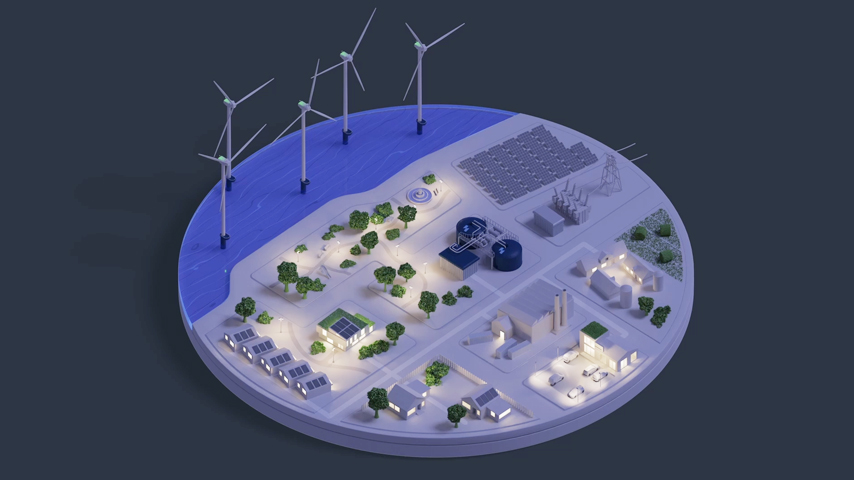

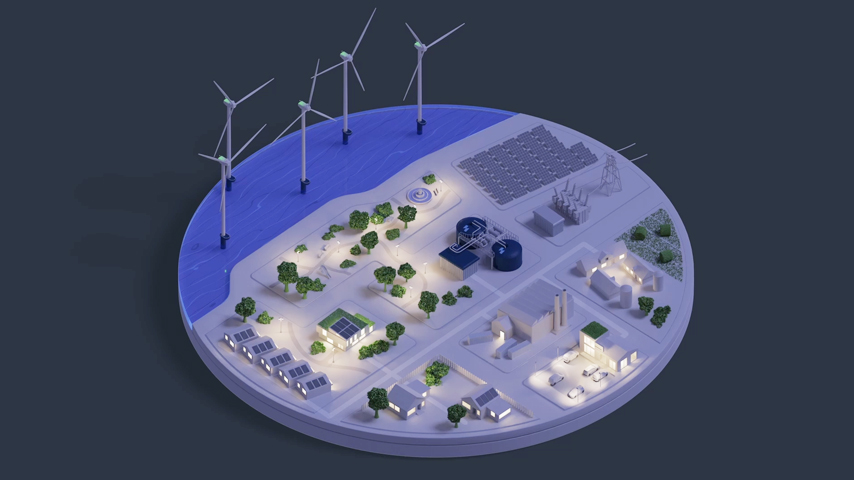

The hunt for the cheapest, greenest, most efficient way to store energy from solar and wind when the sun goes down and the winds are at a standstill continues apace. Potential storage systems in some stage of development abound: Giant batteries, underground vaults for compressed air, flywheels, and the hauling of heavy weights to high places, are all in the works to keep electricity flowing at night and when the air is still.

Molten salt is another option. The concept is simple enough: Heat up the salts when the energy is coming in and let that heat power a turbine when the sun and wind are no longer doing their thing. Molten salt is already in use for concentrated solar power systems, but currently it comes with a serious downside: The salts that have been used so far (the most common of which is sodium nitrate and potassium nitrate) don’t get hot enough. As a result, molten salt delivers electricity with about 70 percent efficiency.

However, a Danish company, Hyme Energy, has turned to a different salt, sodium hydroxide. They can heat this material to 1,292 °F, some 930-odd degrees hotter than other molten salt storage formulations. The higher temperatures, and lower cost of the salt, bring Hyme’s solution to a higher efficiency. Their solution can absorb large amounts of energy, store it, and dispatch it for up to 24 hours (compared to lithium-ion storage systems which charge up fast but discharge within eight hours).

When the heat from Hyme’s system is used to as heat, instead of just to power a turbine, it can reach efficiencies of over 90 percent. The company is targeting industry and consumers that need heat.

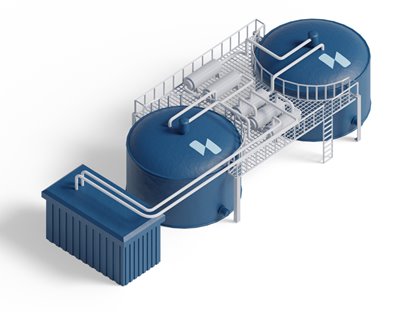

Demonstration system

Hyme now has two demonstration facilities in the works. The first is a pilot project in collaboration with a utility company in the seaport town of Esbjerg and two component suppliers, Alfa Laval and Sulzer, for a 1.5-MW storage unit. It will be commissioned this year. “The first project will basically be an integration project to test components and system integration,” said Reuben Munnee, Hyme’s head of engineering. “But it will be connected and dispatch heat to the district heating network.” They also have plans to build a 15-MWh to 20-MWh hour storage facility on Denmark’s energy island, Bornholm, in 2024.

Become a Member: How to Join ASME

The Hyme system is essentially just two storage tanks, one for heated salt, the other for cooled salt—down at 572 °F—after its heat has been sent out of the system as steam for heat or to power a turbine. It’s small enough to fit into existing power plants and put the turbines already there to use. In fact, the Bornholm storage system will be installed in a cogeneration plant. The Hyme storage unit will replace an oil boiler in the power plant and provide steam, power, and heat for the district. It’s one part of the utility company’s efforts to decommission their fossil-based assets.

Hyme owes the viability of its system to the salt they’re using. Not only does sodium hydroxide hold more heat, but it is also a mere tenth of the cost of other salts. It can easily be pulled out of ocean water and is a byproduct of chlorine production.

Corrosive material

But there’s a big reason sodium hydroxide hasn’t been used before—it’s highly corrosive. With a pH of 14, it is more caustic than lye. It’s the key ingredient in drain cleaners.

Similar Reading: Solar Storage When the Sun Goes Down

Hyme’s sister company, Seaborg Technologies, had been trying to find ways of handling the stuff for use in small modular nuclear reactors. The company eventually developed a patented corrosion control system that allows the salt to sit in its tanks without melting them. Since Hyme doesn’t have to jump through the regulatory hoops necessary to put a nuclear reactor in operation, they are likely to use the corrosion control system long before Seaborg does.

Depending on their success in Esbjerg and Bornholm, molten salt may soon help reduce fossil fuel dependency while keeping the electricity flowing when the air is calm and the sun is down.

Michael Abrams is a technology writer in Westfield, N.J.