Tiny Robots Now Can Explore and Treat the Body

Tiny Robots Now Can Explore and Treat the Body

A McMaster roboticist is developing tiny magnetic robots that have the ability to deliver drugs, take biopsies, and explore hard to reach areas inside the human body.

While some roboticists spend their time building bodies for their bots, others build bots to go inside bodies.

That has been the single goal that Onaizah Onaizah has pursued as a roboticist in McMaster University’s Department of Computing and Software, where she runs the HeART lab. It’s there she develops millimeter-scale robots that are able to go inside the body to take samples, deliver drugs to specific targets, and explore cavities and caverns.

Long before Onaizah began working at this Fantastic Voyage stuff, she studied physics—first as an undergraduate and then earning a master’s in medical physics, for which she modeled blood flow through carotid arteries to see how altering it can lead to a stroke.

“One of the things that I very quickly realized was that I didn’t want to be a quantum physicist—I wanted to work in an application area,” she said. “Medical physics might seem very different, but the fundamentals were a lot of the same—a lot of it was fluid modeling. So just going from the big climate fluid modeling to modeling fluids inside of the body.”

While earning her Ph.D., she started working on safer microfluidic devices and that soon led to microrobots.

Minimally invasive surgery has been, for some time, the goal of researchers developing advanced surgical tools. But they end up working where it’s easiest for their tools to reach, like in the abdomen. “But it becomes a lot more challenging for procedures in the brain [and] in the lungs, where you have a lot more tortuous pathways, and the space is a lot smaller,” Onaizah said.

Now, with her own lab, she is continuing to develop tiny tools for medicine and surgery that can get to the hardest-to-access parts of the body. That research follows three (arguably less tortuous than the convolutions found in the body) pathways.

The first of these is a 3D printer for soft magnetic robots. If you want to send a robot into the body, it’s better if it’s soft—so it doesn’t bang things up too badly during its travels—and magnetic, so it can be guided from outside the body. But making such a thing is currently an incredibly painstaking process.

“You have to go to the clean room to make the mold, and then someone literally sits under a microscope and assembles these devices by hand using a pair of tweezers under a microscope. And it can take anywhere from two to four days, depending on how many devices you’re assembling,” Onaizah said. “What we wanted to do was really figure out if there is a way that we could automate this procedure.”

An undergraduate, Jackson Sholdice had seen Onaizah on the popular science-oriented YouTube channel Veritasium, and he wanted to help her create a way to 3D print soft magnetic robots. His solution was to abandon the usually rigid polymers used in 3D printing and instead mix magnetic particles into a UV resin. Then the printer could be programmed to determine the orientation of the particles. “That allows us to create functional devices in whatever shape and magnetization profile that we want,” Onaizah said.

The ability to do just that has helped her and her team with the other two primary research goals of the lab. One of those is a probe that can navigate the sinuses. The ones that are used now are rigid, uncomfortable for the patient, and too inflexible to reach some of the smaller sinus passages. And surgeons often must drill through bone just to see what’s going on in a specific area.

“Navigating the complex nasal passages—and also facial surgery—can be very traumatizing,” Onaizah said. “If we can design flexible probes that can actually navigate some of those anatomical curvatures in our sinuses, and access locations where they don’t have to cut someone’s face open, would be huge in the world of healthcare.”

“Navigating the complex nasal passages—and also facial surgery—can be very traumatizing,” Onaizah said. “If we can design flexible probes that can actually navigate some of those anatomical curvatures in our sinuses, and access locations where they don’t have to cut someone’s face open, would be huge in the world of healthcare.”

The robotic probe that she and her team are working on would be able to remove fluid, deliver drugs, and possibly even perform laser ablation of any detected polyps—as well as provide both pre- and post-op visualization.

Their current version is soft all over, has a diameter of two millimeters, and can bend in any direction. It’s also equipped with lasers, cameras, and suctioning and drug delivery tools. And, of course, it’s moved by magnets at its tip and along its length. Once it’s inserted, the probe is controlled entirely by magnetic field. The team is currently working on making a magnetic actuation system that is under the table, clear of the surgeon’s workspace.

But there are other places in the body more opaque and less accessible than the sinuses. “One of the challenges that we have in the human body is—obviously—as soon as you put something inside, you can’t see it anymore,” Onaizah said. “In robotics, we love doing vision and tracking using cameras, but you lose that as soon as something goes inside the human body, which is actually a great challenge.”

The PillCam, now owned by Medtronic, which has been on the market for nearly a quarter of a century, did something to illuminate, literally, the small intestine. But its movements are dictated by the whims of the GI tract. “If you actually see a problem area, there’s no way for you to navigate to that target location and image or biopsy it more closely, because everything is passive,” Onaizah said.

The answer—perhaps obviously, coming from Onaizah’s lab—is magnets. They will allow her capsule to be steered to a target area, for the purposes of visualization and drug delivery. And, as McMaster has its own nuclear reactor on campus, Onaizah’s team may soon be able to use radioisotopes to track the capsule as well as deliver radio pharmaceuticals. Little doors at one end of the capsules, also controlled by a magnetic field outside the body, can open at one end to release those or any other pharmaceuticals.

There’s one other ability the capsule has that gives it the potential to revolutionize not only diagnosis, but also our general knowledge of the gut. The little doors that can deliver drugs may also be able to close and, with tiny blades and needles, gather tissue samples. This will allow doctors to take a biopsy from inside the stomach or intestines.

It will also allow us to finally learn exactly what’s living inside us. Right now, what we know of the gut microbiome of any individual comes only from stool samples. “There’s actually no way of figuring out what bacteria lives there and what is the good bacteria and bad bacteria,” Onaizah said. “So, a capsule that can collect a sample from different regions of the GI tract would be really advantageous.”

As of now, that capsule, though 3D printed, requires hand assembly—it initially took four days to finish. They’ve worked on cutting that down and it now takes 20 minutes to put together one capsule. But Onaizah is hoping to reduce that further. Regardless of how long it takes to make, the capsule is almost ready for in vitro testing, first with pigs. But before that happens, it will have to be tweaked to survive porcine munching. “As a human, you’re very much willing to swallow a capsule, but you can’t actually get pigs to do it,” she said. “They end up just chewing on the capsule and sort of breaking it down.” So, she’s looking to use more flexible materials that could survive mastication.

Once the pigs pave the way—which Onaizah says could happen in five years or so—we may soon be swallowing robots to keep ourselves alive.

Michael Abrams is a technology writer in Westfield, N.J.

That has been the single goal that Onaizah Onaizah has pursued as a roboticist in McMaster University’s Department of Computing and Software, where she runs the HeART lab. It’s there she develops millimeter-scale robots that are able to go inside the body to take samples, deliver drugs to specific targets, and explore cavities and caverns.

Monitoring inside the body

Long before Onaizah began working at this Fantastic Voyage stuff, she studied physics—first as an undergraduate and then earning a master’s in medical physics, for which she modeled blood flow through carotid arteries to see how altering it can lead to a stroke.“One of the things that I very quickly realized was that I didn’t want to be a quantum physicist—I wanted to work in an application area,” she said. “Medical physics might seem very different, but the fundamentals were a lot of the same—a lot of it was fluid modeling. So just going from the big climate fluid modeling to modeling fluids inside of the body.”

While earning her Ph.D., she started working on safer microfluidic devices and that soon led to microrobots.

Minimally invasive surgery has been, for some time, the goal of researchers developing advanced surgical tools. But they end up working where it’s easiest for their tools to reach, like in the abdomen. “But it becomes a lot more challenging for procedures in the brain [and] in the lungs, where you have a lot more tortuous pathways, and the space is a lot smaller,” Onaizah said.

Tiny tools

Now, with her own lab, she is continuing to develop tiny tools for medicine and surgery that can get to the hardest-to-access parts of the body. That research follows three (arguably less tortuous than the convolutions found in the body) pathways.The first of these is a 3D printer for soft magnetic robots. If you want to send a robot into the body, it’s better if it’s soft—so it doesn’t bang things up too badly during its travels—and magnetic, so it can be guided from outside the body. But making such a thing is currently an incredibly painstaking process.

“You have to go to the clean room to make the mold, and then someone literally sits under a microscope and assembles these devices by hand using a pair of tweezers under a microscope. And it can take anywhere from two to four days, depending on how many devices you’re assembling,” Onaizah said. “What we wanted to do was really figure out if there is a way that we could automate this procedure.”

An undergraduate, Jackson Sholdice had seen Onaizah on the popular science-oriented YouTube channel Veritasium, and he wanted to help her create a way to 3D print soft magnetic robots. His solution was to abandon the usually rigid polymers used in 3D printing and instead mix magnetic particles into a UV resin. Then the printer could be programmed to determine the orientation of the particles. “That allows us to create functional devices in whatever shape and magnetization profile that we want,” Onaizah said.

The ability to do just that has helped her and her team with the other two primary research goals of the lab. One of those is a probe that can navigate the sinuses. The ones that are used now are rigid, uncomfortable for the patient, and too inflexible to reach some of the smaller sinus passages. And surgeons often must drill through bone just to see what’s going on in a specific area.

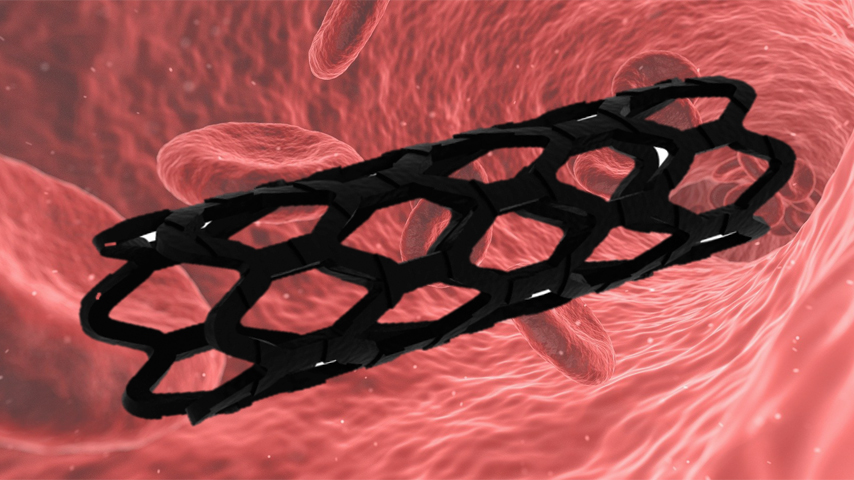

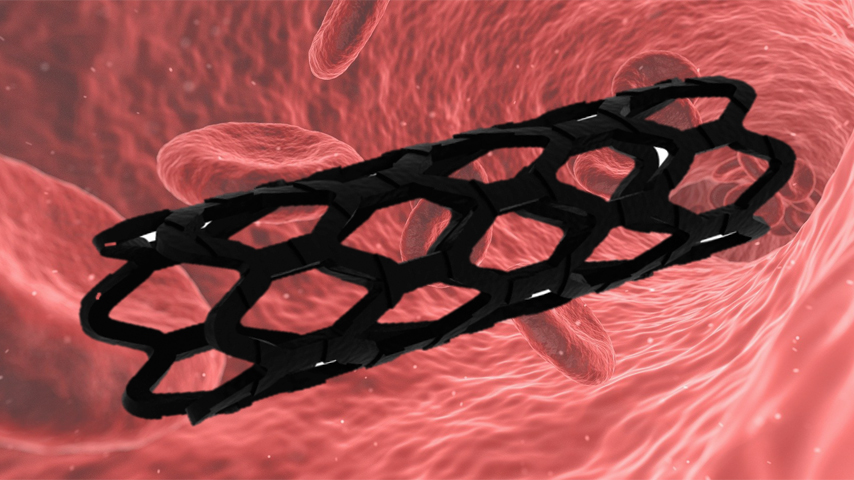

Miniature Robots to Navigate Blood Vessel Networks

Newly developed magnetically actuated soft robots can reach and treat hard-to-reach areas inside the body.

The robotic probe that she and her team are working on would be able to remove fluid, deliver drugs, and possibly even perform laser ablation of any detected polyps—as well as provide both pre- and post-op visualization.

Their current version is soft all over, has a diameter of two millimeters, and can bend in any direction. It’s also equipped with lasers, cameras, and suctioning and drug delivery tools. And, of course, it’s moved by magnets at its tip and along its length. Once it’s inserted, the probe is controlled entirely by magnetic field. The team is currently working on making a magnetic actuation system that is under the table, clear of the surgeon’s workspace.

But there are other places in the body more opaque and less accessible than the sinuses. “One of the challenges that we have in the human body is—obviously—as soon as you put something inside, you can’t see it anymore,” Onaizah said. “In robotics, we love doing vision and tracking using cameras, but you lose that as soon as something goes inside the human body, which is actually a great challenge.”

The PillCam, now owned by Medtronic, which has been on the market for nearly a quarter of a century, did something to illuminate, literally, the small intestine. But its movements are dictated by the whims of the GI tract. “If you actually see a problem area, there’s no way for you to navigate to that target location and image or biopsy it more closely, because everything is passive,” Onaizah said.

Future direction

The answer—perhaps obviously, coming from Onaizah’s lab—is magnets. They will allow her capsule to be steered to a target area, for the purposes of visualization and drug delivery. And, as McMaster has its own nuclear reactor on campus, Onaizah’s team may soon be able to use radioisotopes to track the capsule as well as deliver radio pharmaceuticals. Little doors at one end of the capsules, also controlled by a magnetic field outside the body, can open at one end to release those or any other pharmaceuticals.There’s one other ability the capsule has that gives it the potential to revolutionize not only diagnosis, but also our general knowledge of the gut. The little doors that can deliver drugs may also be able to close and, with tiny blades and needles, gather tissue samples. This will allow doctors to take a biopsy from inside the stomach or intestines.

It will also allow us to finally learn exactly what’s living inside us. Right now, what we know of the gut microbiome of any individual comes only from stool samples. “There’s actually no way of figuring out what bacteria lives there and what is the good bacteria and bad bacteria,” Onaizah said. “So, a capsule that can collect a sample from different regions of the GI tract would be really advantageous.”

As of now, that capsule, though 3D printed, requires hand assembly—it initially took four days to finish. They’ve worked on cutting that down and it now takes 20 minutes to put together one capsule. But Onaizah is hoping to reduce that further. Regardless of how long it takes to make, the capsule is almost ready for in vitro testing, first with pigs. But before that happens, it will have to be tweaked to survive porcine munching. “As a human, you’re very much willing to swallow a capsule, but you can’t actually get pigs to do it,” she said. “They end up just chewing on the capsule and sort of breaking it down.” So, she’s looking to use more flexible materials that could survive mastication.

Once the pigs pave the way—which Onaizah says could happen in five years or so—we may soon be swallowing robots to keep ourselves alive.

Michael Abrams is a technology writer in Westfield, N.J.