Measuring Mental Fatigue with an e-Tattoo

Measuring Mental Fatigue with an e-Tattoo

With U.S. employees reporting high rates of burnout, a new wireless e-tattoo system can help measure mental strain during onerous tasks.

The employee burnout epidemic is growing. In a recent Moodle survey, researchers found that more than 80 percent of younger employees are reporting symptoms of burnout, including persistent fatigue, lack of motivation, escalating stress levels, and increased irritability at work. While this epidemic is of concern in any industry, it could mean life or death for workers in air traffic control, surgery, emergency response, or other high-stress positions.

“We’ve seen in the news that air traffic controllers are incredibly understaffed right now. You may have one controller who has to do multiple people’s jobs,” said Nanshu Lu, Carol Cockrell Curran Chair in Engineering in the Department of Aerospace Engineering and Engineering Mechanics at the University of Texas at Austin. “This kind of job is hard on its own, but when you add more stress, it can increase the possibility of a big miscalculation.”

Because technology is at such a breakneck pace, Lu said, human workers are feeling the stress. Certainly, the Moodle survey bears that out: 24 percent of respondents said they have more work to complete than time to do it and 19 percent said they are forced to take on too much due to staffing shortages in their industry. But, if you could reliably measure mental strain, organizations could help predict who is at the highest risk of making a mistake, Lu said.

You Might Also Enjoy: A Mechanical Biomarker for Brain Health?

“It’s well known that the frontal lobe is responsible for reasoning, calculation, decision-making, and working memory—which are all important for occupational tasks,” Lu continued. “While you could use traditional electroencephalography [EEG] to make these kinds of measurements, and see increased activity with increased task demands, they are very time consuming to set up and also quite uncomfortable to wear.”

There is also the problem of eye movements contaminating the brain wave data. Eye movement generates much higher voltages than true EEG signals, Lu noted. Any less bulky device would have to find a way to filter out that noise or use it in some way to help with predictions of mental fatigue.

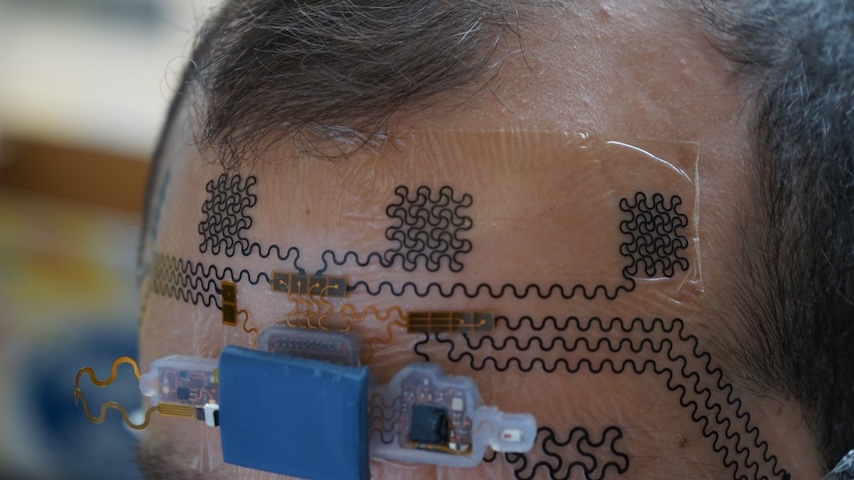

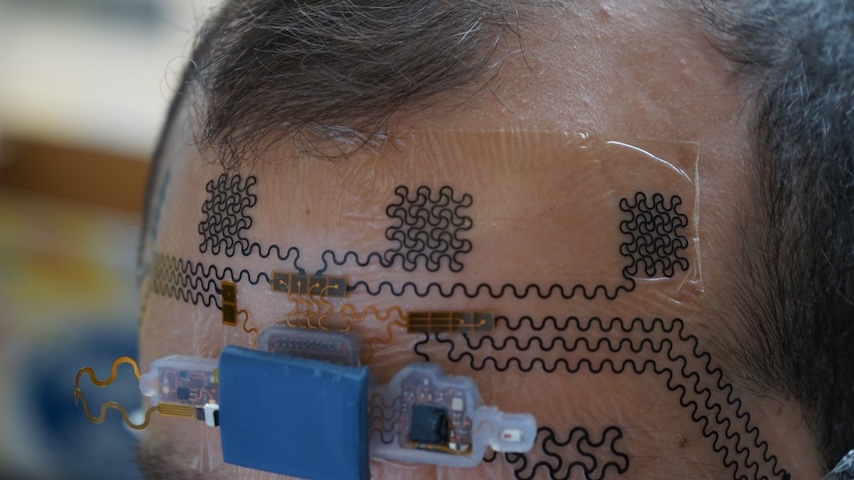

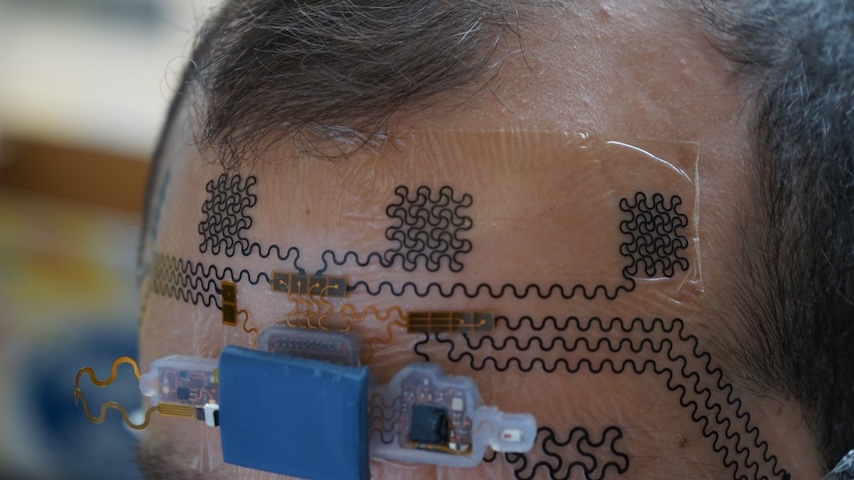

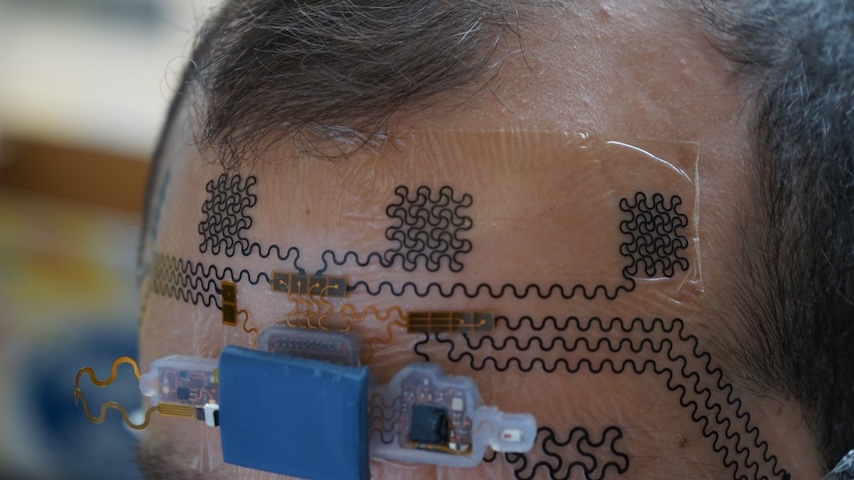

Lu’s lab is well known for its e-tattoo solutions: soft, wearable devices that adhere directly to the skin like a temporary tattoo. To measure cognitive workload in people, she and her colleagues have developed a new type of untethered e-tattoo device that can measure activity in the brain, as well as eye movements. This wireless device has paper-thin sensors that are coated with Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS) and applied to the forehead. The sensors are designed to be flexible, with loops and coils to clearly catch brain waves, as well as a small, lightweight battery pack to power the device.

“The PEDOT:PSS has both ionic and electrical conductivity and because this coating is also a little bit adhesive, it adheres the sensors very well to the forehead,” she said. “As a result, we can measure very high quality, very high-fidelity brain waves.”

The device also includes electrooculography (EOG) sensors, which can measure eye movements. Taken together, the e-tattoo can collect alpha, beta, theta, and delta brainwaves, as well as eye gaze changes, which are then fed into an algorithm to determine whether individuals are experiencing mental stress.

“When mental load goes up, you see changes in brain activity,” Lu said. “Our algorithm also uses EOG to subtract eye noise from the EEG signals to minimize eye movement contamination. But we also use EOG to analyze eye blinking frequency or eye fixation. And we found that information is marginally useful to helping to accurately decode an increase in mental workload.”

Discover the Benefits of ASME Membership

The researchers tested the e-tattoo device on a group of six study participants as they performed a well-validated cognitive challenge known as the dual N-back task. This exercise stresses working memory by presenting two streams of information, visual and auditory, and requires participants to recall the stimuli that was presented n (where n increases to increase difficulty) steps back in each sequence. It is a cognitively demanding task—and Lu found that the e-tattoo results correlated well with results from a paper metric called the NASA Task Load Index, a self-reported survey about the difficulty of a particular task. Lu was surprised at how well the e-tattoo could measure cognitive load, as well as predict when people were becoming mentally overwhelmed.

“Before, many people suggested you have to measure many channels across the head to decode mental workload,” she said. “We prove that it is possible to get these signals just from the forehead.”

To further test the device, Lu and colleagues plan to move the device out of the lab and try to collect more real-life working environment data so these e-tattoos could one day be used to identify workers at risk of burnout or errors.

“Because our device is so mobile, easy to use, and not obstructive to helmets or doctor’s hats, we could look at the transportation workforce or surgeons in the operating room,” she said. “We are currently looking at opportunities to do this so we can better measure and track mental strain in these important jobs.”

Kayt Sukel is a technology writer and author in Houston.

“We’ve seen in the news that air traffic controllers are incredibly understaffed right now. You may have one controller who has to do multiple people’s jobs,” said Nanshu Lu, Carol Cockrell Curran Chair in Engineering in the Department of Aerospace Engineering and Engineering Mechanics at the University of Texas at Austin. “This kind of job is hard on its own, but when you add more stress, it can increase the possibility of a big miscalculation.”

Because technology is at such a breakneck pace, Lu said, human workers are feeling the stress. Certainly, the Moodle survey bears that out: 24 percent of respondents said they have more work to complete than time to do it and 19 percent said they are forced to take on too much due to staffing shortages in their industry. But, if you could reliably measure mental strain, organizations could help predict who is at the highest risk of making a mistake, Lu said.

You Might Also Enjoy: A Mechanical Biomarker for Brain Health?

“It’s well known that the frontal lobe is responsible for reasoning, calculation, decision-making, and working memory—which are all important for occupational tasks,” Lu continued. “While you could use traditional electroencephalography [EEG] to make these kinds of measurements, and see increased activity with increased task demands, they are very time consuming to set up and also quite uncomfortable to wear.”

There is also the problem of eye movements contaminating the brain wave data. Eye movement generates much higher voltages than true EEG signals, Lu noted. Any less bulky device would have to find a way to filter out that noise or use it in some way to help with predictions of mental fatigue.

Lu’s lab is well known for its e-tattoo solutions: soft, wearable devices that adhere directly to the skin like a temporary tattoo. To measure cognitive workload in people, she and her colleagues have developed a new type of untethered e-tattoo device that can measure activity in the brain, as well as eye movements. This wireless device has paper-thin sensors that are coated with Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS) and applied to the forehead. The sensors are designed to be flexible, with loops and coils to clearly catch brain waves, as well as a small, lightweight battery pack to power the device.

“The PEDOT:PSS has both ionic and electrical conductivity and because this coating is also a little bit adhesive, it adheres the sensors very well to the forehead,” she said. “As a result, we can measure very high quality, very high-fidelity brain waves.”

The device also includes electrooculography (EOG) sensors, which can measure eye movements. Taken together, the e-tattoo can collect alpha, beta, theta, and delta brainwaves, as well as eye gaze changes, which are then fed into an algorithm to determine whether individuals are experiencing mental stress.

“When mental load goes up, you see changes in brain activity,” Lu said. “Our algorithm also uses EOG to subtract eye noise from the EEG signals to minimize eye movement contamination. But we also use EOG to analyze eye blinking frequency or eye fixation. And we found that information is marginally useful to helping to accurately decode an increase in mental workload.”

Discover the Benefits of ASME Membership

The researchers tested the e-tattoo device on a group of six study participants as they performed a well-validated cognitive challenge known as the dual N-back task. This exercise stresses working memory by presenting two streams of information, visual and auditory, and requires participants to recall the stimuli that was presented n (where n increases to increase difficulty) steps back in each sequence. It is a cognitively demanding task—and Lu found that the e-tattoo results correlated well with results from a paper metric called the NASA Task Load Index, a self-reported survey about the difficulty of a particular task. Lu was surprised at how well the e-tattoo could measure cognitive load, as well as predict when people were becoming mentally overwhelmed.

“Before, many people suggested you have to measure many channels across the head to decode mental workload,” she said. “We prove that it is possible to get these signals just from the forehead.”

To further test the device, Lu and colleagues plan to move the device out of the lab and try to collect more real-life working environment data so these e-tattoos could one day be used to identify workers at risk of burnout or errors.

“Because our device is so mobile, easy to use, and not obstructive to helmets or doctor’s hats, we could look at the transportation workforce or surgeons in the operating room,” she said. “We are currently looking at opportunities to do this so we can better measure and track mental strain in these important jobs.”

Kayt Sukel is a technology writer and author in Houston.