Intercepting Water Plastic Pollution

Intercepting Water Plastic Pollution

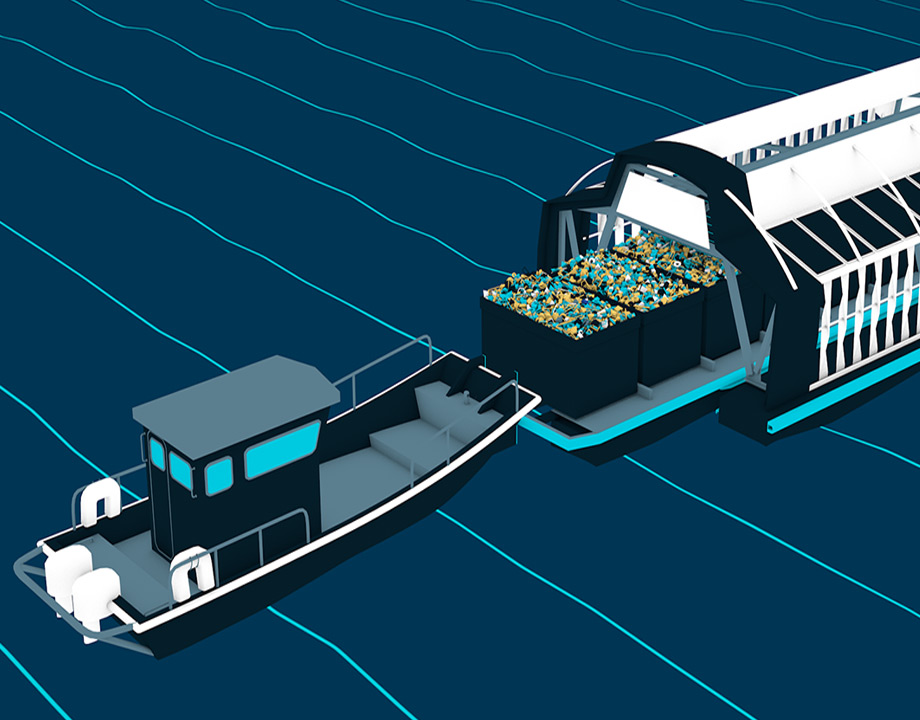

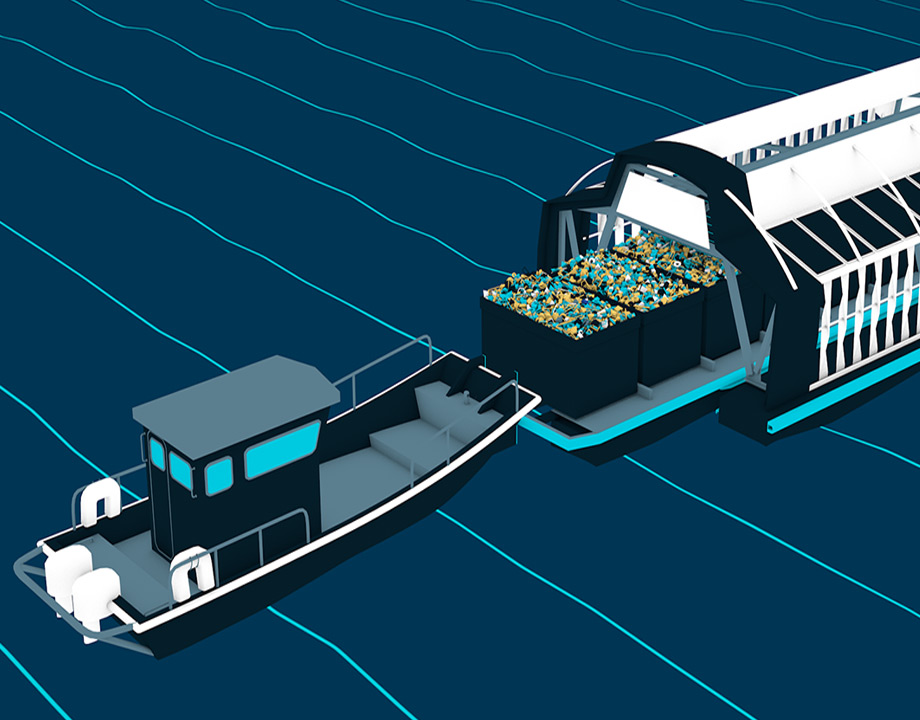

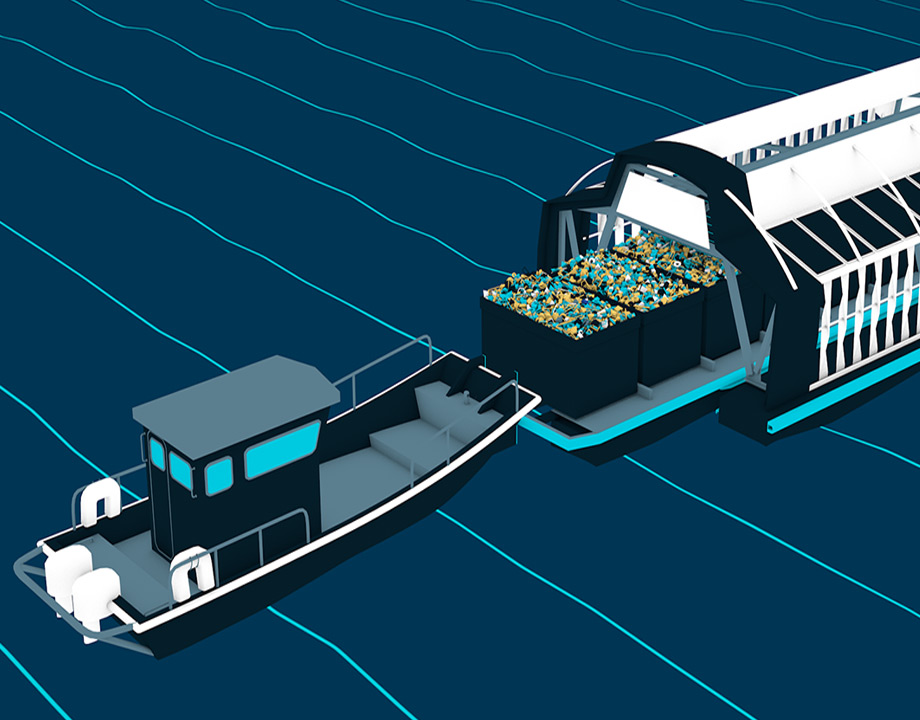

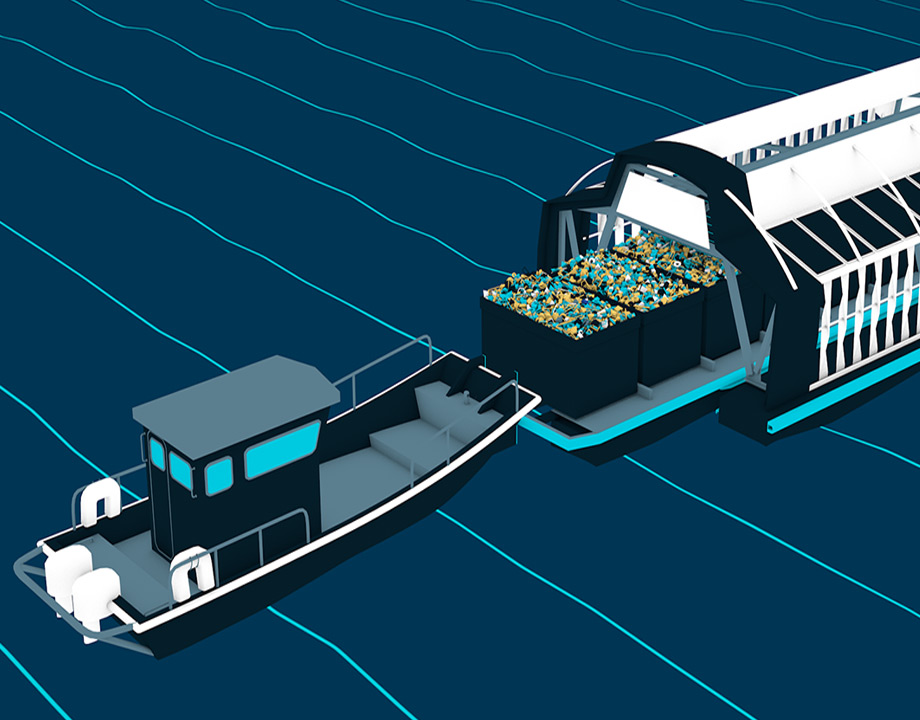

The Interceptor sits in a river, nabbing plastic trash before it hits the high seas. Photo: The Ocean Cleanup

The folks behind The Ocean Cleanup have begun the process of removing a small portion of the astonishing mass of garbage—mostly plastic—fouling our seas. Right now they are focused on the Great Pacific garbage patch (also known as the Pacific trash vortex), a 1.6 million square kilometer gyre of marine debris.

However successful the project winds up being, the job will never be complete as long as trash continues to flow into the oceans. About 80 percent of that flow comes from the 1,000 or so rivers that feed into the seas. So, to stop refuse at the source, the Delft, Netherlands-based Ocean Cleanup has turned to river cleanup.

“One of our foundational principles is that, in order to solve a problem, you must first understand it,” project engineer Matthias Van Middendorp said. “We quickly realized that to be truly effective in our mission to rid the oceans of plastic, we will need to significantly decrease the influx of plastics.”

To do that, they’ve developed Interceptor, a barge-shaped boat to sift river waters and catch trash before it reaches the sea.

The boat is essentially a catamaran with a conveyor belt in the middle. It sits near one river bank while a long boom extends upstream to the opposite bank. As plastic floats down the river, it hits the boom and runs along it till it meets the mouth of the boat. There, the permeable conveyor belt picks the waste out of the water and carries it to one of several bins on board, while letting the water fall back to the river.

Further Reading: Solar Desalination System Delivers High Energy Output

“This allows the debris to continue flowing up to the conveyor belt while not interrupting the path of the water,” said Sjoerd Drenkelford, the project’s installation officer.

The gap between Interceptor and the near bank enables other vessels to pass unobstructed. In cases where garbage might also escape through this opening—when the boat is downstream from a bend in the river, for example—a second boom can be placed upstream to direct the trash to the collecting boom.

The design of Interceptor has changed significantly since its first inception. The boat and conveyor belt are larger than they were in initial designs, and the boat is more buoyant.

“From a technical perspective, the main challenge we encountered was the storage medium,” Van Middendorp said. “Initially we were using big bags, which turned out to be a poor fit for all types of debris, such as bigger branches.”

Further Reading: A Robot Crab to Clean the Ocean

The bags also required a worker to remove them. Now the boat—powered by solar panels on its roof—can work autonomously for much longer, as debris is automatically distributed across six dumpsters. Interceptor can store as much as 50 cubic meters of trash; when the bins are full, they can be removed and sent to local recycling facilities.

The Ocean Cleanup has produced four Interceptor-class boats, and two of them are already cleaning rivers in Indonesia and Malaysia. One is destined for Vietnam and another is soon to be put to work in the Dominican Republic.

With the boats now in the water, the engineers who designed the river sifters have learned a few lessons.

“From a project point of view, there is more attention for the actual site where Interceptors will be deployed to ensure the quay is according to our specs and the tools are working; now we are sorting these things out beforehand with local partners prior to sending an Interceptor to the country,” Drenkelford said. “We have learned that it is not just the system, but the system around the system as well. Everything needs to work properly, or none of it can work at all.”

There are some 31,000 rivers in the world. Though the project is certainly scalable, Drenkelford and Van Middendorp are the first to admit that it’s only one part of the solution toward the ultimate goal: The Interceptor not only cleans polluted waters, it draws attention to the problem and the need to stop the flow of plastic.

Said, Van Middendorp: “We want to put ourselves out of business.”

Michael Abrams is a technology writer based in Westfield, N.J.

However successful the project winds up being, the job will never be complete as long as trash continues to flow into the oceans. About 80 percent of that flow comes from the 1,000 or so rivers that feed into the seas. So, to stop refuse at the source, the Delft, Netherlands-based Ocean Cleanup has turned to river cleanup.

“One of our foundational principles is that, in order to solve a problem, you must first understand it,” project engineer Matthias Van Middendorp said. “We quickly realized that to be truly effective in our mission to rid the oceans of plastic, we will need to significantly decrease the influx of plastics.”

To do that, they’ve developed Interceptor, a barge-shaped boat to sift river waters and catch trash before it reaches the sea.

The boat is essentially a catamaran with a conveyor belt in the middle. It sits near one river bank while a long boom extends upstream to the opposite bank. As plastic floats down the river, it hits the boom and runs along it till it meets the mouth of the boat. There, the permeable conveyor belt picks the waste out of the water and carries it to one of several bins on board, while letting the water fall back to the river.

Further Reading: Solar Desalination System Delivers High Energy Output

“This allows the debris to continue flowing up to the conveyor belt while not interrupting the path of the water,” said Sjoerd Drenkelford, the project’s installation officer.

The gap between Interceptor and the near bank enables other vessels to pass unobstructed. In cases where garbage might also escape through this opening—when the boat is downstream from a bend in the river, for example—a second boom can be placed upstream to direct the trash to the collecting boom.

The design of Interceptor has changed significantly since its first inception. The boat and conveyor belt are larger than they were in initial designs, and the boat is more buoyant.

“From a technical perspective, the main challenge we encountered was the storage medium,” Van Middendorp said. “Initially we were using big bags, which turned out to be a poor fit for all types of debris, such as bigger branches.”

Further Reading: A Robot Crab to Clean the Ocean

The bags also required a worker to remove them. Now the boat—powered by solar panels on its roof—can work autonomously for much longer, as debris is automatically distributed across six dumpsters. Interceptor can store as much as 50 cubic meters of trash; when the bins are full, they can be removed and sent to local recycling facilities.

The Ocean Cleanup has produced four Interceptor-class boats, and two of them are already cleaning rivers in Indonesia and Malaysia. One is destined for Vietnam and another is soon to be put to work in the Dominican Republic.

With the boats now in the water, the engineers who designed the river sifters have learned a few lessons.

“From a project point of view, there is more attention for the actual site where Interceptors will be deployed to ensure the quay is according to our specs and the tools are working; now we are sorting these things out beforehand with local partners prior to sending an Interceptor to the country,” Drenkelford said. “We have learned that it is not just the system, but the system around the system as well. Everything needs to work properly, or none of it can work at all.”

There are some 31,000 rivers in the world. Though the project is certainly scalable, Drenkelford and Van Middendorp are the first to admit that it’s only one part of the solution toward the ultimate goal: The Interceptor not only cleans polluted waters, it draws attention to the problem and the need to stop the flow of plastic.

Said, Van Middendorp: “We want to put ourselves out of business.”

Michael Abrams is a technology writer based in Westfield, N.J.

.png?width=854&height=480&ext=.png)