The Robot Therapist Is Open for Business

The Robot Therapist Is Open for Business

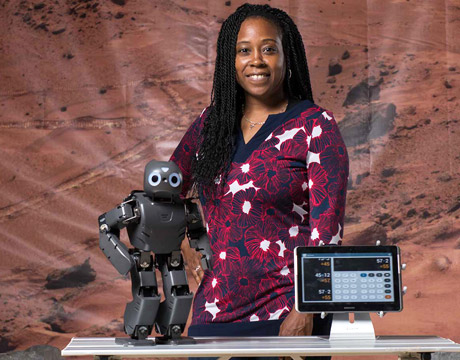

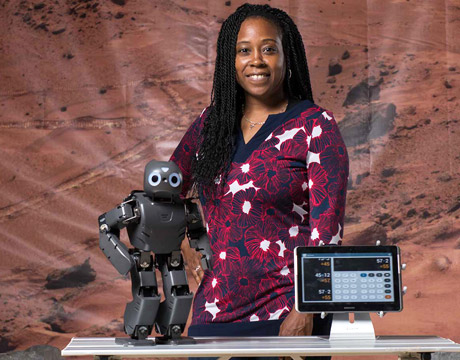

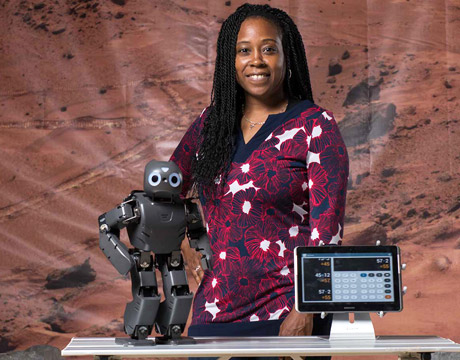

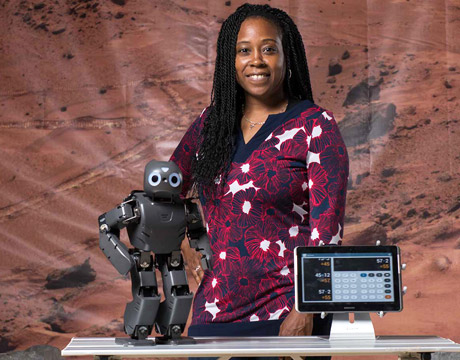

Professor-researcher-roboticist Ayanna Howard is living her dream—bringing together her fascination with robotics and her childhood desire to be involved in the medical field. In so doing, she is harnessing the power of robotics to captivate and serve a very special constituency: children with special needs.

Collaborating with clinicians, Howard, director of Georgia Tech’s Human-Automation Systems Lab, and her team are developing an innovative virtual reality system that will allow various types of patient-specific therapy to take place in the home without a therapist present.

The system of devices and software will replicate and replace the interactions that take place when a therapist is on site whether, for example, promoting physical movement for children with motor disabilities or behavioral responses for autistic children.

The hope is that widespread deployment is just three or so years away, dependent on whether one of several new robotics startups develop a platform that will meet her needs — something akin to downloading an app on a tablet — and bring down costs from the $8,000 robot currently being used for testing to about $1,500. The child will have the robot and customized software that will include games and other interactive modules, prescribed by the clinician based on what the child is to work on.

The first program tested was for children with cerebral palsy, who have difficulty with movement. The testing that started about 18 months ago for up to eight-week sessions took place with a therapist present. The child sits in front of a video screen to play a game called “Super Pop,” basically popping bubbles that move on the screen.

If, for example, the child needs to work on speed of movement, the robot, typically placed to the left of the child, will say, “Hey, let’s play a game. I want you to play.” The robot demonstrates playing the game, all the while communicating with the child. Then the child plays, and the robot provides feedback. A follow-up could be playing the same game faster or working on another skills besides speed.

One of the biggest challengesis developing the robotic system so that it functions as a human therapist in a clinical setting, providing feedback by monitoring the child’s performance, says Howard.

“It needs to not only provide motivation like ‘That’s a good job’ but also needs to recognize if the child is struggling. One typical outcome in moving faster is that another parameter gets weaker,” says Howard. One example would be “I might move faster but my arm isn’t straight,” she notes.

“An experienced therapist knows exactly what type of feedback to give a child to change that,” she says, and that’s how the system needs to operate as well.

Another challenge is creating a system that’s robust but easy for non-engineers to use. The team is also addressing questions like what happens if the robot, which also includes a camera providing a visual for the clinician, is not placed in exactly the right spot and is slightly off. “Maybe the robot can be trained to adapt itself to deal with an inexperienced environment,” she says.

Prior to widespread deployment, the system needs more games and more and larger clinical studies. “A really good clinical study would be about 25 to 30 kids at the same time for something over six months,” she says. The team has also just started a study for children with autism, focused on turn-taking and other activities in order to encourage appropriate behavior.

Despite Howard’s childhood desire to go to medical school, a plan she abandoned for robotics after realizing in biology class that dissecting frogs wasn’t her thing, she spent more than a decade at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratories, designing “smarter” robots using artificial intelligence for the next generation of the Mars rover. When NASA cut its research budget, she chose to join Georgia Tech to continue her research in robotics there.

During the summers, she ran robotics camps for children that included both mainstream kids and children with special needs, all interacting and learning how to program robots. One year, when a teenage camper had a visual impairment, Howard began thinking about accessibility. In doing some research, she learned that an “astounding” percentage of children had some sort of disability.

“Here [at camp] I’d been preaching that it’s all about diversity and inclusiveness,” she says.“I discovered there was this whole entire unmet need to [provide] children with special needs access to what we consider basic things such as education.”

Her first project was creating technology that would allow kids with disabilities to program robots. Then, as she came in contact with clinicians and therapists, they said it’s nice to get kids to program and open up their minds, but there were needs on the clinical side. That’s when, collaborating with clinicians, she started looking at how robotic systems could be used for therapy.

Nancy Giges is an independent writer.

Here I’d been preaching that it’s all about diversity and inclusiveness, and I discovered there was this whole entire unmet need to [provide] children with special needs access to basic things.Prof. Ayanna Howard, Georgia Tech