Blog: Hydropower’s Grid-Scale Storage and Generation Potential

Blog: Hydropower’s Grid-Scale Storage and Generation Potential

New research indicates closed-loop pumped storage hydropower systems have the lowest global warming impact compared to other energy storage methods.

One of the oldest forms of renewable energy, hydropower comprises a decent chunk of the United States’ green energy portfolio. According to the Energy Information Administration (EIA), in 2022, hydroelectricity made up about 6.2 percent of all U.S. utility-scale electricity generation, as well as 28.7 percent of total utility-scale renewable electricity generation. Thanks to increasing use of other types of renewable energy such as solar and wind, hydropower perhaps doesn’t get quite the same attention these days. The EIA notes that hydroelectricity's percentage share of total annual U.S. electricity generation in 2001 through 2022 averaged about 6.7 percent.

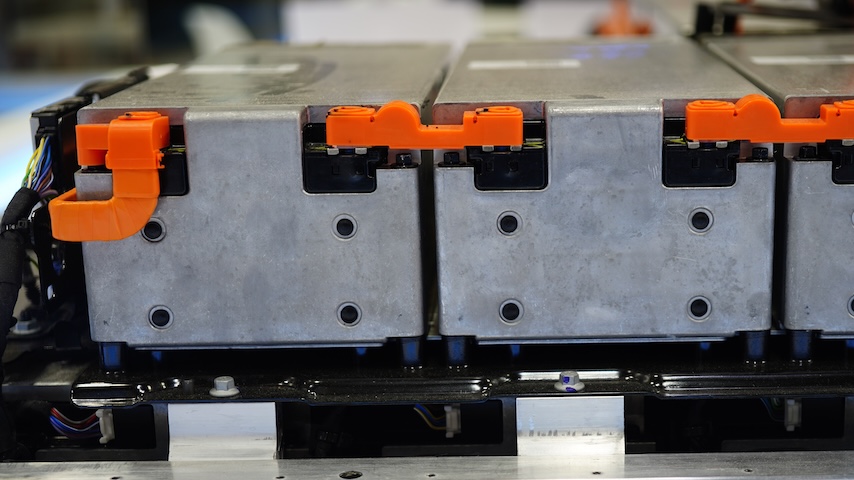

But new research out of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) indicates that closed-loop pumped storage hydropower (PSH) systems—which rely on water flowing between two reservoirs to generate and store power—actually have the lowest potential of contributing to global warming for energy storage, when accounting for the full impacts of materials and construction, compared to other energy storage methods.

Published in August in the Environmental Science and Technology, “Life Cycle Assessment of Closed-Loop Pumped Storage Hydropower in the United States” compares these closed-loop systems to other grid-scale storage technologies.

Researchers explain that since renewable sources like solar and wind don’t continuously generate power, they risk curtailment, a situation where excess electricity is made but not used. This is where storing excess power could play a role.

The study found that the global warming potential (GWP) of a closed-loop PSH ranges from 58 grams of carbon dioxide per kWh to 530 g CO2e kWh, while “the stored electricity grid mix [has] the largest impact, followed by concrete used in facility construction. Additionally, PSH site characteristics can have a substantive impact on GWP, with brownfield sites resulting in a 20 percent lower GWP compared to greenfield sites." That suggests closed-loop PSH offers climate benefits over other energy storage technologies, the researchers wrote.

Overall, hydropower offered the lowest GWP on a functional unit basis, followed by utility-scale lithium-ion batteries (LIBs), vanadium redox flow batteries (VRFBs), compressed-air energy storage (CAES), and utility-scale lead-acid (PbAc) batteries—the four other technologies against which researchers compared PSH.

According to NREL, PSH systems actually provide 93 percent of the United States’ grid-scale energy storage today. The agency explains that PSH’s ability produce energy on demand could make it a significant factor in a clean energy grid, as the energy storage it provides could integrate with other types of generation like solar and wind. But NREL also recognized that developing new PSH systems would take major investment and would also require certain types of geographic features to maximize energy storage with minimal environmental impacts.

It’s interesting to note these findings, in light of the Biden-Harris Administration announcing plans just this past March to invest more than $200 million in modernizing and expanding hydropower across the country.

Supported by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, this announcement saw the Department of Energy open applications for two hydroelectric incentives under the Hydroelectric Incentives Program, to focus on maintaining and enhancing hydroelectric facilities as well as improving dam safety and reducing environmental impacts.

But DOE noted that currently less than 3 percent of the more than 90,000 dams across the United States produce any power. If generation equipment were added to those sites, they could add up to 12 gigawatts of new hydropower capacity across the country.

Federal entities like the Bureau of Reclamation and Army Corps of Engineers own about 52 percent of hydropower generation, with the other 48 percent owned by private and public utilities. But federal entities operate 133 hydroelectric power plants, just 8 percent of U.S. hydroelectric facilities. The remaining 92 percent are non-federal facilities, totaling 1,623 hydropower facilities in every region of the U.S., 89 percent of which have capacities of less than 30 MW.

And it looks like changes are already in the works to perhaps embrace additional hydropower on existing infrastructure. On Sept. 1, for example, the Corps announced plans for public information sessions in mid-September about the role of hydropower at the Willamette Valley dams in Oregon.

It’s just one more piece of the growing renewable energy puzzle that could help reduce reliance on traditional energy resources.

Louise Poirier is senior editor.