Big Metal 3D Printing Startup Out of a Garage

Big Metal 3D Printing Startup Out of a Garage

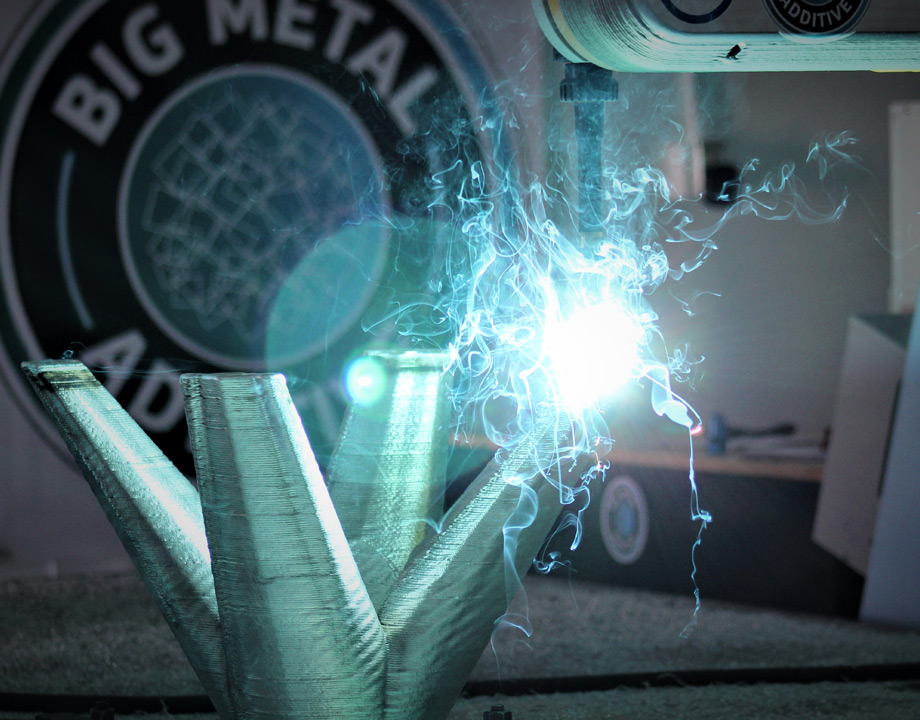

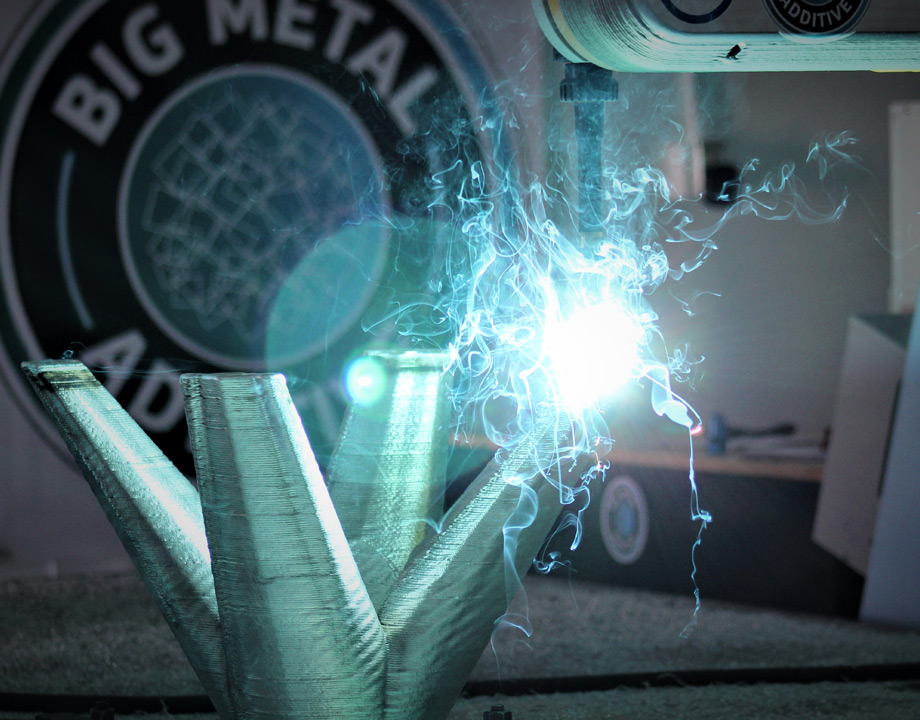

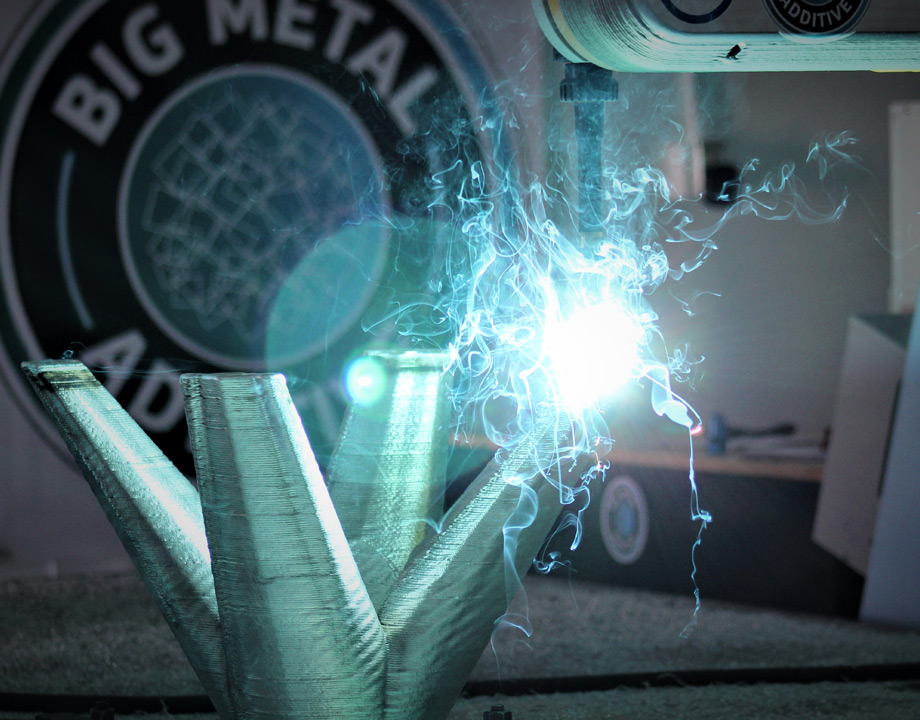

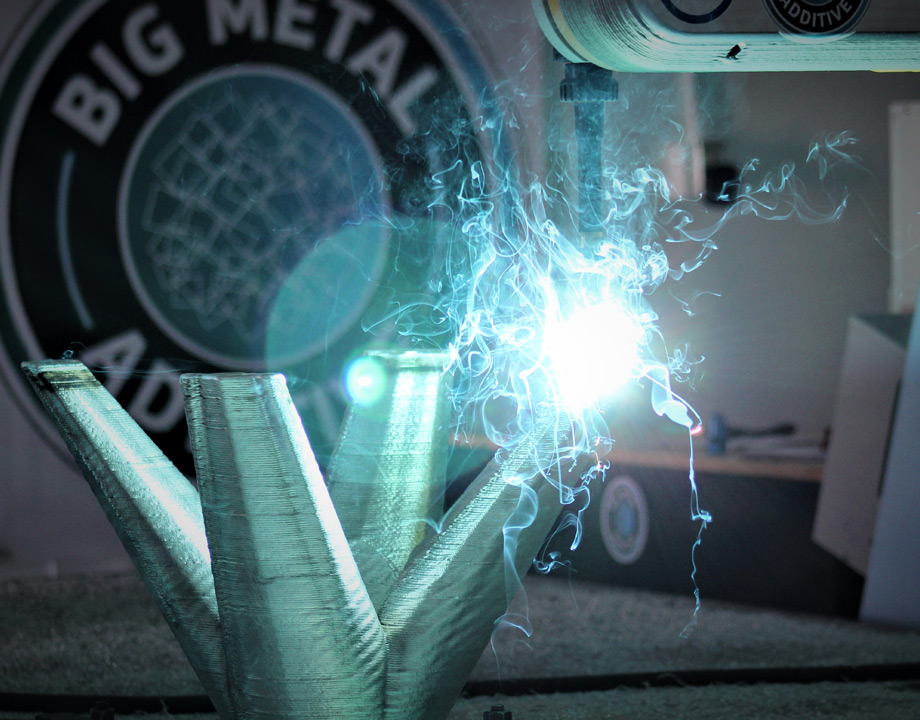

The self-financed factory-ready hybrid 3D printer can make large metal parts in the open air. Photo: Big Metal Additive

Garage engineering startups still exist, and Big Metal Additive is an ambitious example. The company’s self-financed hybrid 3D metal printer combines high-speed arc wire additive manufacturing with five-axis CNC machining. The resulting system is optimized to make trusses, auto chassis, enclosures, tooling and fixtures, beams, architectural elements, and other large parts.

Big Metal’s current workspace measures 6 by 12 by 4 feet with deposition rates of up to 5 pound per hour. It could achieve even faster deposition speeds and unlimited build volumes by adding more print heads, company founder and president Slade Gardner said.

The printer is built to work alongside other factory equipment, Gardner added. It operates in open spaces without vacuums or inert environments, and yields finished parts with true anisotropic properties. It also uses conventional industrial control systems and workflows, so experienced machinists can treat it just like any other industrial machine.

Gardner founded the company after a career on the edge of 3D printing as a leader in Lockheed-Martin’s effort to print titanium fuel tanks for rockets and satellite structures.

“I’ve been doing metal additive manufacturing since the early 2000s,” he said. “I studied all the processes and knew arc wire would be the best.”

Arc wire works by melting an alloy wire with an electrode to form tiny droplets. Everything takes place in the open, using only a stream of gas to shield the workpiece from contamination. It was developed for welding, but several companies have adapted it for additive manufacturing. Big Metal is now one of them.

While arc wire is known for its speed, it has other advantages, too.

“It delivers metal to point of deposition with a precisely known mass and delivery rate,” Gardner said. “Wire is the most efficient form factor to minimize surface area, which in turn minimizes surface contaminants, oxidation, and debris.”

Further Reading: Laser Printer Evolves to 3D Printing

Most metal additive printers work only with specialized alloys that melt and consolidate easily. Big Metal uses eight commercial aluminum arc welding alloys, which are a lot less costly. Gardner expects to add stainless and tool steels, superalloys, and titanium in the future.

The system uses its five-axis CNC machine to improve deposition quality by machining each deposited layer so it is perfectly flat. This removes surface oxidation, contaminants, and debris and leaves an ideal surface on which to build the next layer.

“We have a consistent, known layer height for every layer,” Gardner said. “That manifests as better dimensional tolerance in the final part."

Adding a CNC machine lets workers re-machine parts if any layers drift out of spec. It also addresses some of the problems Gardner dealt with when he tried to print thicker metal walls at Lockheed-Martin.

“Single wall wire-fed builds were kind of straightforward,” he said. “But when we got into thicker walls—two or three beads wide—we wound up with a rippled surface. That has always been a problem because troughs invited defects. I always wanted a way to eliminate those troughs.”

Of course, the CNC machine can do more than flatten the work surface. Equipped with a tool changer with ten different cutting tools, it can also do surfacing, chamfering, profiling, and a wide range of other operations.

Further Reading: New 3D Printer Extruder Takes Manufacturing to Next Level

“You could finish the part as you make it, so it’s ready to use when done,” Gardner said.

Because Gardner wanted factories to think of his 3D printer as just another tool, he took an unusual approach to control.

“Our machine runs on an industrial grade numerical controller, the type used in CNC machines,” Gardner said. “It runs just like a numerical controller on a lathe, mill, or turning center. There is a very large, skilled workforce who already know how to use that controller. Workers can step up to the pedestal and they already know how to operate our machine.”

Just like conventional machinery, users can turn off a Big Metal printer in mid-operation and resume the build the next day or the next week.

“We had a blizzard that knocked out power to our building,” Gardner recalled. “When it came on a week later, we milled off one half-built layer and resumed processing. Others would have had to scrap the part.”

Big Metal’s system also uses industrial software that uses computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) to convert solid CAD models to path instructions for the hybrid additive machine. No one has to use conventional 3D STL slicing algorithms to build the part.

“The big benefit of this is that if you’re a manufacturing engineer, you already know how to plan for our machine,” Gardner said. “You don’t have to learn anything new."

The resulting system builds on proven low-cost technologies (wire arc, CNC machining) and materials (wire alloys) and existing workforce skills. This may give potential users a price advantage in the marketplace.

Further Reading: Chain Reaction

Big Metal thinks the market is big enough to price aggressively. It plans to sell a 3-axis hybrid machine with a 2 by 2 by 2 feet build space for less than $300,000. This is much lower than any other metal additive machine on the market, Gardner said.

“We want the process we’ve designed to become widespread,” he explained. “We want it everywhere, from hot rod shops to maintenance to prototype design shops. It is very competitive for manufacturing prototypes, production runs of tens or hundreds of parts, and applications where you consolidate many parts into a single article.”

It sounds ambitious, but well within the range of what many other garage engineering startups have accomplished.

Alan S. Brown is senior editor.

Big Metal’s current workspace measures 6 by 12 by 4 feet with deposition rates of up to 5 pound per hour. It could achieve even faster deposition speeds and unlimited build volumes by adding more print heads, company founder and president Slade Gardner said.

The printer is built to work alongside other factory equipment, Gardner added. It operates in open spaces without vacuums or inert environments, and yields finished parts with true anisotropic properties. It also uses conventional industrial control systems and workflows, so experienced machinists can treat it just like any other industrial machine.

Hybrid Production

Gardner founded the company after a career on the edge of 3D printing as a leader in Lockheed-Martin’s effort to print titanium fuel tanks for rockets and satellite structures.

“I’ve been doing metal additive manufacturing since the early 2000s,” he said. “I studied all the processes and knew arc wire would be the best.”

Arc wire works by melting an alloy wire with an electrode to form tiny droplets. Everything takes place in the open, using only a stream of gas to shield the workpiece from contamination. It was developed for welding, but several companies have adapted it for additive manufacturing. Big Metal is now one of them.

While arc wire is known for its speed, it has other advantages, too.

“It delivers metal to point of deposition with a precisely known mass and delivery rate,” Gardner said. “Wire is the most efficient form factor to minimize surface area, which in turn minimizes surface contaminants, oxidation, and debris.”

Further Reading: Laser Printer Evolves to 3D Printing

Most metal additive printers work only with specialized alloys that melt and consolidate easily. Big Metal uses eight commercial aluminum arc welding alloys, which are a lot less costly. Gardner expects to add stainless and tool steels, superalloys, and titanium in the future.

The system uses its five-axis CNC machine to improve deposition quality by machining each deposited layer so it is perfectly flat. This removes surface oxidation, contaminants, and debris and leaves an ideal surface on which to build the next layer.

“We have a consistent, known layer height for every layer,” Gardner said. “That manifests as better dimensional tolerance in the final part."

Adding a CNC machine lets workers re-machine parts if any layers drift out of spec. It also addresses some of the problems Gardner dealt with when he tried to print thicker metal walls at Lockheed-Martin.

“Single wall wire-fed builds were kind of straightforward,” he said. “But when we got into thicker walls—two or three beads wide—we wound up with a rippled surface. That has always been a problem because troughs invited defects. I always wanted a way to eliminate those troughs.”

Of course, the CNC machine can do more than flatten the work surface. Equipped with a tool changer with ten different cutting tools, it can also do surfacing, chamfering, profiling, and a wide range of other operations.

Further Reading: New 3D Printer Extruder Takes Manufacturing to Next Level

“You could finish the part as you make it, so it’s ready to use when done,” Gardner said.

Because Gardner wanted factories to think of his 3D printer as just another tool, he took an unusual approach to control.

Factory Ready

“Our machine runs on an industrial grade numerical controller, the type used in CNC machines,” Gardner said. “It runs just like a numerical controller on a lathe, mill, or turning center. There is a very large, skilled workforce who already know how to use that controller. Workers can step up to the pedestal and they already know how to operate our machine.”

Just like conventional machinery, users can turn off a Big Metal printer in mid-operation and resume the build the next day or the next week.

“We had a blizzard that knocked out power to our building,” Gardner recalled. “When it came on a week later, we milled off one half-built layer and resumed processing. Others would have had to scrap the part.”

Big Metal’s system also uses industrial software that uses computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) to convert solid CAD models to path instructions for the hybrid additive machine. No one has to use conventional 3D STL slicing algorithms to build the part.

“The big benefit of this is that if you’re a manufacturing engineer, you already know how to plan for our machine,” Gardner said. “You don’t have to learn anything new."

The resulting system builds on proven low-cost technologies (wire arc, CNC machining) and materials (wire alloys) and existing workforce skills. This may give potential users a price advantage in the marketplace.

Further Reading: Chain Reaction

Big Metal thinks the market is big enough to price aggressively. It plans to sell a 3-axis hybrid machine with a 2 by 2 by 2 feet build space for less than $300,000. This is much lower than any other metal additive machine on the market, Gardner said.

“We want the process we’ve designed to become widespread,” he explained. “We want it everywhere, from hot rod shops to maintenance to prototype design shops. It is very competitive for manufacturing prototypes, production runs of tens or hundreds of parts, and applications where you consolidate many parts into a single article.”

It sounds ambitious, but well within the range of what many other garage engineering startups have accomplished.

Alan S. Brown is senior editor.