ASME Presidents and Globalization

ASME Presidents and Globalization

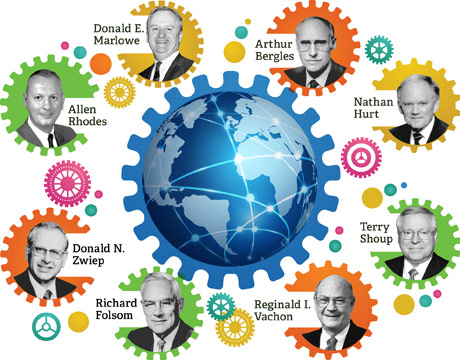

For the first 90 or so years of its existence, ASME concerned itself chiefly with engineering in the United States. But as the Society’s focus shifted outward in the last few decades of the twentieth century, ASME’s presidents played a pivotal role.

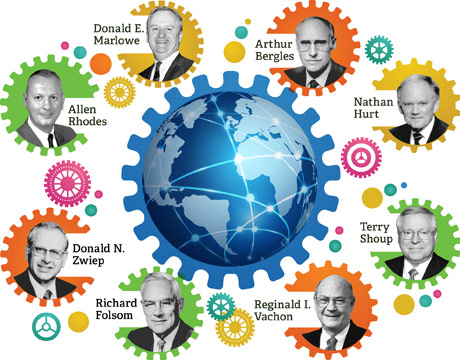

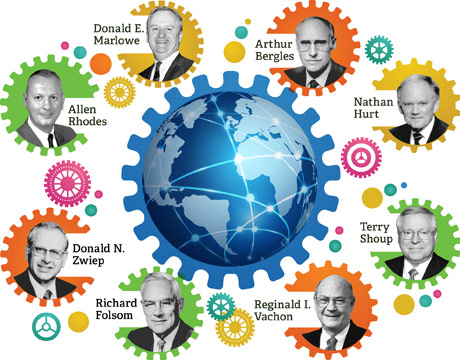

Since the 1970s, ASME presidents have increasingly traveled the globe to represent ASME as signatories to international agreements, to forge alliances and friendships among ASME’s international counterparts, and to serve as the face of an increasingly global society that understands engineering to be important not just in the U.S., but everywhere. As Richard Folsom (ASME President, 1972-73) said in an oral history interview: “We’ve got to look at engineering on an international basis, to have an influence and gain experience.”

ASME made the formal decision to expand into the international arena at a now-legendary 1970 Goals Conference known as “Arden House.” Donald E. Marlowe (ASME President, 1969-70) convened the historic conference to re-envision all of the Society’s activity for a new era. It was at Arden House that ASME declared that “strengthen[ing] the ties among engineers worldwide" would become one of the Society’s official goals for the future.

This declaration quickly confronted the governors with a consequential choice: Should they change ASME’s name to reflect its international aims? Or should ASME remain an “American Society” as it opened to the world? Happily, said Donald N. Zwiep (ASME President, 1979-80), Society leaders decided to keep the ASME name, remain the “American Society,” and embrace a globalizing future by establishing partnerships with sister organizations around the globe. ASME decided, said Zwiep, to “help the ME organizations in (other) countries … rather than amalgamate them as part of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.” In his own oral history, Allen Rhodes (ASME President, 1970-71) agreed with this approach; Rhodes thought it better “to work on the international scene as an American society” too.

Vickie Rockwell (ASME President, 2011-2012 ) at a UNESCO Signing ceremony in June 2012.

In the years following Arden House, ASME set about building those agreements of cooperation with its sister societies around the world. To make it happen, ASME presidents were called into service as the Society’s global ambassadors. Among them, Arthur Bergles (ASME President, 1990-91) was among the most traveled. “We celebrated the 20th year [of international partnership-building]” said Bergles, “by signing agreements of cooperation with engineering societies in France, Belgium, Italy, Norway, Yugoslavia, Argentina and Israel, bringing the total then to 28.”

Nathan Hurt (ASME President, 1991-92) spent much of his tenure traveling the globe on behalf of ASME as well. Hurt described leading international missions to formal summits with engineering societies in Australia, Colombia, France, Germany, Greece, Hong Kong, Israel and Singapore.

By that time, ASME’s presidents had come to expect extensive global travel for much of their terms – an enriching and surprisingly demanding new requirement of the job.

Beyond their ambassadorial work, many ASME leaders of recent decades also came to believe Society members must be ready for an increasingly international engineering marketplace. In his presidential term in 2003-04, Reggie Vachon advocated for a “Mobility of Engineering Credentials” working group for this reason. “With globalization,” said Vachon, “engineers are going to have to prepare themselves to be able to practice across geopolitical boundaries.” He believes strongly that “we're in a world where people have to interact, and the practice of engineering is across borders.”

ASME’s leaders had also come to see engineering itself as an international activity. “The earth's atmosphere, the ozone layers which are disappearing, this is an international problem,” said Folsom in his oral history interview.

ASME had evolved to see its responsibility as including but by no means limited to the scope of U.S. engineering. To Terry Shoup (ASME President, 2006-07), the continuing need for international focus was clear: “The fastest-growing segment of our membership population is from outside the United States. Our codes and standards are now in places where they weren't before. Our technical conferences are more global than they've ever been before,” said Shoup in his oral history interview. Shoup was pleased that ASME has “pushed globalization as an important priority for what we are doing and how we're doing it.”

View a video clip from ASME’s Oral History with Terry E. Shoup.

Thus a tradition begun in 1970 is still going strong today. When ASME first made the decision to reach out to the wider world, its presidents led the way as global ambassadors, policy advocates, and spokespeople for the engineering profession. They’re still doing so today.

© The copyright of this program is owned by ASME.