Stitching Together Coastal Defenses

Stitching Together Coastal Defenses

A network of connected biofriendly mats dubbed the Emerald Tutu may protect shorelines and restore marshlands.

Historically, the most common method of protecting coastal cities and towns from storm-charged waves is to build hardened structures, such as sea walls. But walls have some downsides.

When there’s a storm, a seawall or other hard infrastructure may protect the city from flooding,” said Julia Hopkins, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Northeastern University. “But outside of a storm, seawalls prevent people from accessing the water, and sometimes hard infrastructure can have significant ecological downsides by disrupting things like nutrient transport or sediment transport.”

What’s worse, large infrastructure projects for flood defense just don’t get built. More than a decade after Hurricane Sandy, few if any of the eastern cities and towns that were hit the worst have done much to counter the next one.

Hopkins is researching another ecologically friendly method that not only tames waves, leaves the sea view intact, and allows nutrients go where they must, while also helping restore wetland vegetation.

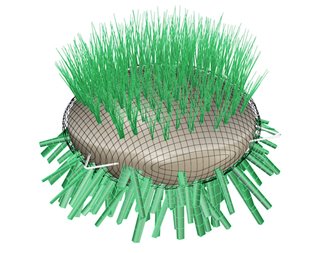

Her concept, called the Emerald Tutu, a play on the name of Boston’s Emerald Necklace park system, is a linked group of floating spherical mats. Each is roughly a meter in diameter, made of a mix of biomass, seeded with marsh grass, and surrounded by a net to hold it all together.

Become a Member: How to Join ASME

The mats are designed for seagrass to on top, and seaweed below. A linked anchor system is threaded through the mats to minimize the risk of any one unit taking the brunt of a wave and being snapped off. The connections between the mats can be designed with slack during calm periods, ideally enough to allow, say, a kayaker, to navigate safely between mats. The aquatic flora is meant to revitalize wetland life systems as well as help dampen wave energy.

Hopkins and her team have tested a linked group of these mats in a wave pool and discovered that the prototype tutu has the capacity to reduce the energy of small, short, waves by 90 percent. This wave reduction lessened as wavelengths got longer, but was still effective with waves up to eight meters in length. With the data from the pool experiments in hand, the team created a model to test multiple configurations of these mats against wave attenuation.

Once you have hundreds of those mats connected to each other, it's really the size and spacing of the network that determines what kind of waves you can dissipate,” Hopkins said.

More for You: Can Engineers Build Floating Cities to Save Island Nations?

That doesn’t mean the researchers are ready to decorate Boston Harbor with a network of biomass buoys. For one thing, they are currently testing a few mat variations—each seeded with different vegetation—to find out which does best through a full cycle of four seasons. Then, with replicas of the winner, they plan to put a 100-unit test network in the water in East Boston, toward the end of 2024. Expanding the system further will require another skill Hopkins has been forced to develop.

Testing things in a lab environment and numerical environment is relatively easy, because there's no permitting process, there's no red tape,” she said. “But to secure the site for our vegetation prototypes, we’ve had to learn how to communicate with municipal leaders and local officials who have concerns about the safety and health of the environment around a given space.”

The spirit of some of the environmental regulations that are in place often are in conflict with the letter of those rules. “The way they were written, they might also block beneficial development,” Hopkins said. “This is something that is actually really critical to fix to get some sort of headway on the climate crisis in general.”

Once Hopkins and her team have run their four-seasons experiment and have mastered the permitting process, the Emerald Tutu will be ready to help dissipate the force of waves and bring back marsh life. But it won’t protect us from big waves and rising seas all by itself.

In terms of coastal resilience, it’s going to have to be a marriage of a bunch of different solutions to tackle different aspects of the coastal problem,” Hopkins said.

Michael Abrams is a science and technology writer in Westfield, N.J.

When there’s a storm, a seawall or other hard infrastructure may protect the city from flooding,” said Julia Hopkins, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Northeastern University. “But outside of a storm, seawalls prevent people from accessing the water, and sometimes hard infrastructure can have significant ecological downsides by disrupting things like nutrient transport or sediment transport.”

What’s worse, large infrastructure projects for flood defense just don’t get built. More than a decade after Hurricane Sandy, few if any of the eastern cities and towns that were hit the worst have done much to counter the next one.

Hopkins is researching another ecologically friendly method that not only tames waves, leaves the sea view intact, and allows nutrients go where they must, while also helping restore wetland vegetation.

Her concept, called the Emerald Tutu, a play on the name of Boston’s Emerald Necklace park system, is a linked group of floating spherical mats. Each is roughly a meter in diameter, made of a mix of biomass, seeded with marsh grass, and surrounded by a net to hold it all together.

Become a Member: How to Join ASME

The mats are designed for seagrass to on top, and seaweed below. A linked anchor system is threaded through the mats to minimize the risk of any one unit taking the brunt of a wave and being snapped off. The connections between the mats can be designed with slack during calm periods, ideally enough to allow, say, a kayaker, to navigate safely between mats. The aquatic flora is meant to revitalize wetland life systems as well as help dampen wave energy.

Hopkins and her team have tested a linked group of these mats in a wave pool and discovered that the prototype tutu has the capacity to reduce the energy of small, short, waves by 90 percent. This wave reduction lessened as wavelengths got longer, but was still effective with waves up to eight meters in length. With the data from the pool experiments in hand, the team created a model to test multiple configurations of these mats against wave attenuation.

Once you have hundreds of those mats connected to each other, it's really the size and spacing of the network that determines what kind of waves you can dissipate,” Hopkins said.

More for You: Can Engineers Build Floating Cities to Save Island Nations?

That doesn’t mean the researchers are ready to decorate Boston Harbor with a network of biomass buoys. For one thing, they are currently testing a few mat variations—each seeded with different vegetation—to find out which does best through a full cycle of four seasons. Then, with replicas of the winner, they plan to put a 100-unit test network in the water in East Boston, toward the end of 2024. Expanding the system further will require another skill Hopkins has been forced to develop.

Testing things in a lab environment and numerical environment is relatively easy, because there's no permitting process, there's no red tape,” she said. “But to secure the site for our vegetation prototypes, we’ve had to learn how to communicate with municipal leaders and local officials who have concerns about the safety and health of the environment around a given space.”

The spirit of some of the environmental regulations that are in place often are in conflict with the letter of those rules. “The way they were written, they might also block beneficial development,” Hopkins said. “This is something that is actually really critical to fix to get some sort of headway on the climate crisis in general.”

Once Hopkins and her team have run their four-seasons experiment and have mastered the permitting process, the Emerald Tutu will be ready to help dissipate the force of waves and bring back marsh life. But it won’t protect us from big waves and rising seas all by itself.

In terms of coastal resilience, it’s going to have to be a marriage of a bunch of different solutions to tackle different aspects of the coastal problem,” Hopkins said.

Michael Abrams is a science and technology writer in Westfield, N.J.