The Intersection of Art and Engineering

The Intersection of Art and Engineering

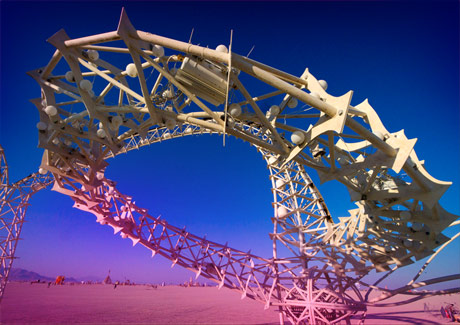

Photo courtesy of Michael Prados.

If you’ve ever tried designing and building a model of the inner ear the size of an airplane hanger and capable of firing off bursts of propane in 56 places, then you know that, whatever the source of inspiration, such a project requires considerably more engineering than art.

Take it from Mike Prados, who helped build just such a structure for this year's "Burning Man," the annual week-long party in Nevada's Black Rock Desert that took place August 29-September 5 this year, and which celebrates wildly diverse forms of self-expression.

"The most substantial parts of the piece are these canals that are depicted as very large curved trusses," says Prados. Assembled, the sculpture's foot print is about 80x 40 feet, with a total weight of between 20,000-25,000 pounds. "It's substantial," says Prados.

Prados is one of forty-odd "Flaming Lotus Girls"—a loose-knit troupe of artists, engineers, and anyone else, who have, for the past 11 years, conceived of, designed, and built massive-scale, fire-breathing works that come to life at the annual party in the desert. By day, he's the director of hardware engineering at Earthmine, a company that makes the tools to produce the "Street View" on Google Maps.

Prados and his compatriots are "Girls" rather than "People" because they are a "female-positive group," he says. "We try to emphasize having women in leadership positions." The goal can often be difficult to achieve, given the lopsided ratio of men to women in the engineering field. "The group has made an effort to educate itself, even if we bring in a few experts who are male."

Regardless of the gender of the people at work on it, a piece as large, complex, and twisted as "Tympani Lambada," as the work is called, requires a certain kind of determination and a certain kind of expertise. Specifically, a large, gangly structure needs both a structural engineer and one of the mechanical sort.

"For these big weird organic forms, mechanical tools are sometimes better," explains Prados. "The bread and butter of most structural engineers is big, boxy buildings like what you and I are sitting in right now."

Starting with the simple concept of reproducing the inner ear in gargantuan proportions, a form "dictated by nature," the group went through dozens of ideas of how to go about it before settling on that most efficient of structures, the truss.

To give the structure its particular form, the Lotus Girls linked the trusses with 140 joints they call "space pigeons" (thanks to their shape that resembles the common bird in astronaut garb; "Someone was up too late," elucidates Prados).

The trusses that the space pigeons hold are propane-carrying pipes. There are 56 fire effects and 28 accumulator tanks. Solenoid valves release propane into what the group calls "poofer boxes," because they, in turn, release giant poofs of propane. "Over the course of an event we go through thousands of gallons of propane—a pretty serious amount of fuel." Poofers, pigeons, and everything between were fabricated by the Lotus Girls.

To translate the project from conception to reality (and make sure it wouldn't fall down), Prados used many of the same tools he uses at his day job. Most of the geometry was constructed in solid works, then exported into a structural analysis program. "Certainly the laws of physics are the same," says Prados

What's different is the shift from the technical to the tactile. "In a world where manufacturing infrastructure is falling apart or moving elsewhere, people find it therapeutic to come in and do things in a manual way—to go into this big messy shop and grab an angle grinder," says Prados.

"I was surprised that anyone could do a project of this scale on a volunteer basis," he says. "I was very pleasantly surprised at how effective it can be. I hope there are lessons here for the larger world."

Michael Abrams is an independent writer.

If you’ve ever tried designing, and building, a model of the inner ear the size of an airplane hanger and capable of firing off bursts of propane in 56 places, then you know that, whatever the source of inspiration, such a project requires considerably more engineering than art.

.png?width=854&height=480&ext=.png)