Glowing Worms Detect Foul Air

Glowing Worms Detect Foul Air

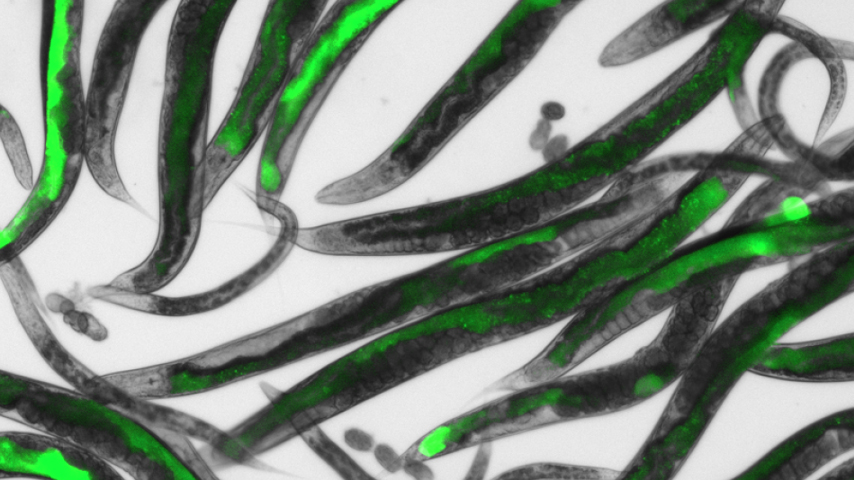

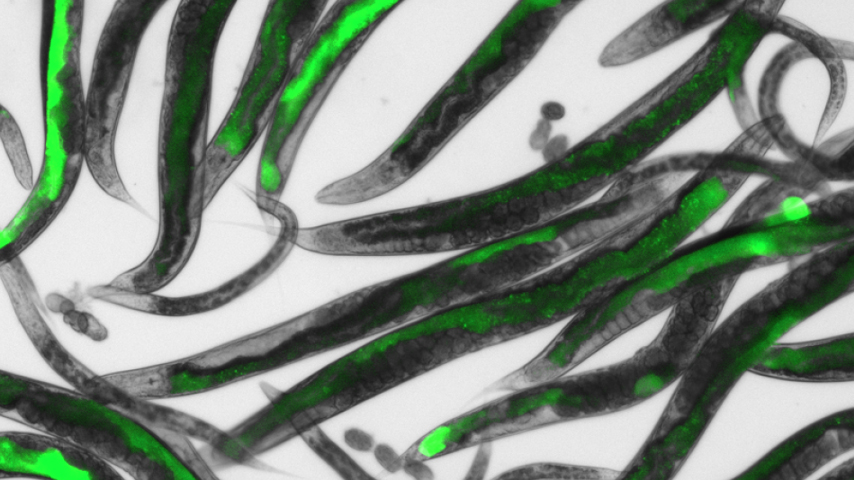

Genetically tweaked nematodes may make a viable sensor for air quality.

“First to fall over when the atmosphere is less than perfect,” sang The Police in the song "Canary in a Coal Mine," back in 1980. The liveliness, or lack thereof, of canaries taken to underground mines was a pretty good indicator of methane and carbon monoxide levels. But for other contaminants that might make the atmosphere less than perfect, above or below ground, there could be of need another kind of sensor, from another kind of life form.

Now, researchers at Finland’s University of Turku have found another living sensor to tell us when air has been befouled: The nematode.

For years, Päivi Koskinen, a lecturer of molecular and cell biology at the university, used the tiny worms in a course she taught on toxicology. The particular strains she was using were transgenic—the wrigglers had a bit of genetic code added to them so that, under certain conditions they glow a fluorescent green. Those conditions, as Koskinen demonstrated in her classes, included exposure to heavy metals and other harmful environmental agents.

To test this discovery more thoroughly, Koskinen and her colleagues placed the nematodes on one side of two-sided plates. In the other compartment they put material that might waft over and bother the nematodes.

“Then they could smell if there was something bad coming from the other side,” said Koskinen. She also used spectrometry to quantitate the amount of fluorescence produced by the exposed animals as compared to an untreated control group.

Become a Member: How to Join ASME

When exposed to toxic fungi, surfactants found in cleaning products, and dangerous compounds produced by degrading phthalates, the nematodes shined bright green.

The transgenic nematodes Koskinen used have long been available to researchers. They produce fluorescence when generally stressed: That is, they have not been engineered to respond to specific compounds. While it would certainly be possible to tweak the genetic code of the worms so they respond to single molecules, it’s not part of Koskinen’s goal.

“What we want to measure is the overall toxicity, because for a person who is in an unhealthy building, it doesn't really matter, what is the thing in the air,” she said. “After you've gotten that initial alarm, you can go in with another tool and try to figure out what it is.”

The next step for Koskinen is to find out how best to get the nematodes out of the lab and working in the real world. A device that monitored the brightness as well as activity of the worms (dead or immobile nematodes are also a sign something’s wrong with the air) could help to determine just when to alert a buildings manager that there’s a problem. She’s already had several companies contact her to help make that happen.

Watch Our Video: Engineering Indoor Air Quality

A nematode pollutant detector is not likely to be monitoring the air in the United States any time soon. Any kind of reporting on the glowing strength of the nematode used by Koskinen, Caenorhabditis elegans, has been patented in Finland.

If the worms are going to be used, they will have to be cultivated. Though that makes the sensor harder to maintain than a smoke detector, it’s simpler than breeding canaries. “They are so easy to grow,” said Koskinen. “So it’s no problem getting thousands of them at the same time.”

Michael Abrams is a science and technology writer in Westfield, N.J.