Increasing the Magnitude of High-Pressure Steam

Increasing the Magnitude of High-Pressure Steam

Irving Edwin Moultrop guided his company and the electric utility industry toward, at that time, unheard of steam pressure ranges. Edgar Station reached 1,200 psi at a time when 300 psi was the norm.

When Edgar Station was fueled by coal, its yards held nearly 300,000 tons of the combustible black material. The days of the 12,000-ton colliers docking and unloading coal at the rate of 800 tons an hour may be gone, but what does remain is the story of the innovative thinking of Boston Edison engineers.

Reliable and efficient, Edgar Station used high-pressure steam to generate electricity. It not only managed to push the envelope of how we thought about how much pressure can be reached “safely” with conventional materials but also established a new record for economy by producing one kilowatt hour of electricity from each pound of coal.

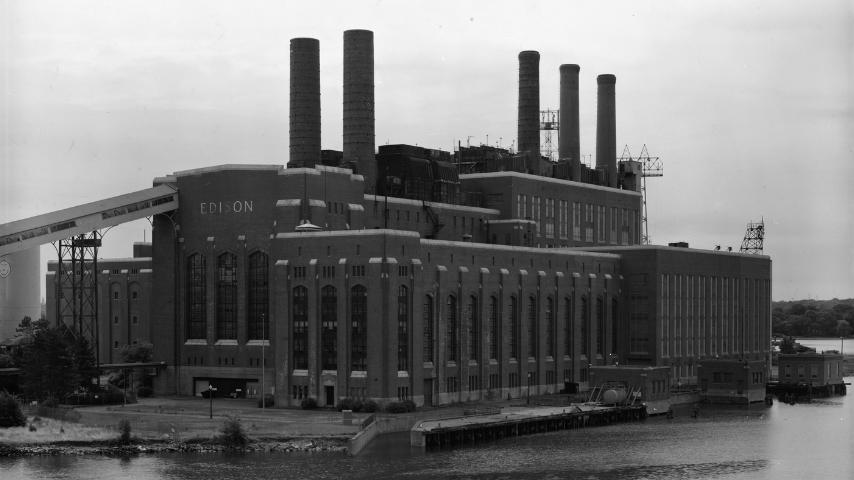

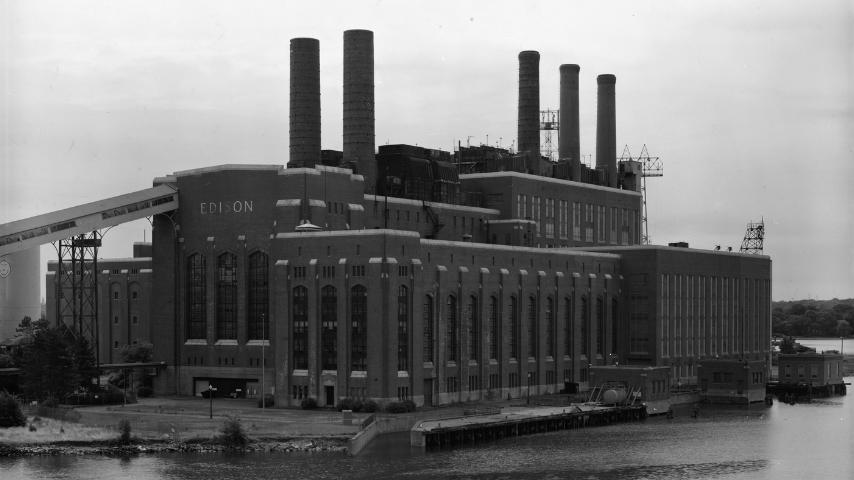

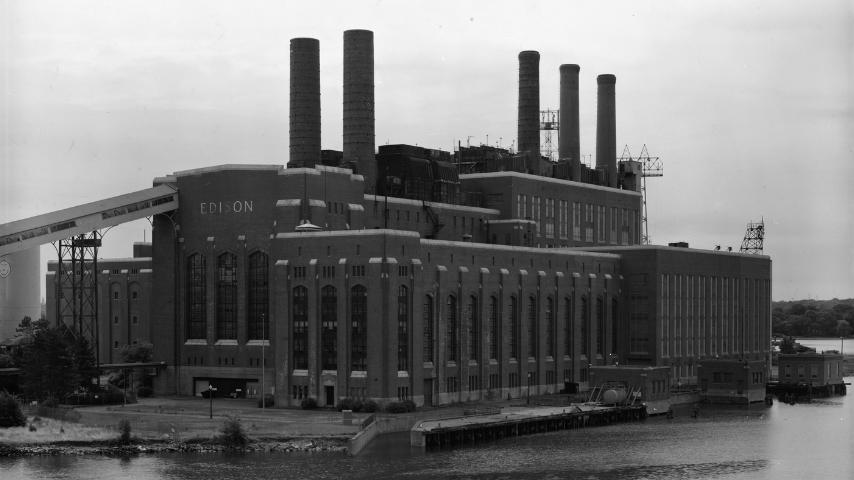

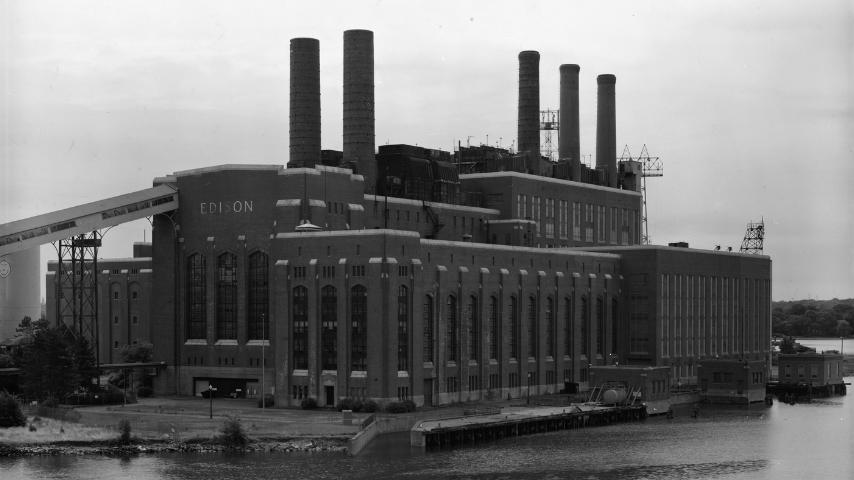

The story of the Edgar Station began in the early 1920s when the Boston Edison Company—then known as the Edison Electric Illuminating Company of Boston—acquired land on the banks of the Fore River in Weymouth, Mass. The property included a deep-water harbor that could handle large coal barges and also provide an inexhaustible supply of water for circulating through power plant condensers.

The high-pressure unit itself was the first one of its kind operating in the world and the station that housed it got its name from the president of Boston Edison, Charles L. Edgar, an electrical engineer who studied under Thomas Alva Edison. But at the center of the project was the assistant superintendent of the construction bureau of Edison Electric, Irving Edwin Moultrop.

At the time of this project Moultrop was in his early 50s and had already enjoyed a career in engineering that spanned decades beginning right after he graduated from Framingham High School and began working for the Whittier Machine Co. in Roxbury. The story of how this engineer, active in work of the ASME Boiler Code Committee, guided his company and the electric utility industry toward the higher-pressure range of 1,200 psi steam is historical.

At that time, steam pressures used to generate electricity ranged in the neighborhood of 300 psi, and the first plant for 500 psi was reportedly in early stages of design. Moreover, it would be some time before the development of molybdenum and, later, chrome-molybdenum alloys that would permit raising steam temperature appreciably.

But there were materials available then that could be used at higher pressures if someone would take the necessary initiative. It was Moultrop, leading the project completed by a team of engineers from the Boston firm Stone & Webster, which took a giant step forward and took the electric utility industry into the higher steam pressure range of 1,200 psi.

After studying the gains in efficiency to be had from higher steam pressures and temperatures, and confined by the limits of then available commercial equipment, it was decided to include in the original development at Weymouth only one 1,200 psi boiler and turbine unit, in conjunction with a 350 psi system (three 350 psi boilers supplying steam at 700 °F to a header feeding steam to two 350 psi turbines).

More for You: The Beauty and Genius of the Fairmount Water Works

The high-pressure steam at 1,200 psi and 700 °F expanded down to 375 psi and 500 °F in the General Electric high-pressure turbine, rated at 3,150 kw. Exhaust steam from this turbine returned to the boiler for reheat to 700 °F, then was discharged to the 350 psi header for supplying the "normal pressure" (350 psi) turbines for expansion to one inch Hg absolute. The two 350 psi turbines were each rated 32,000 kw.

The 1,200-psi steam boiler itself was a modification of the conventional Babcock & Wilcox cross drum type. Its heating surface consisted of two-inch tubes, 15 feet long, arranged in three passes. The drum, a solid steel forging 32 feet long, four feet in diameter, and with walls four inches thick, came from the gun works of the Midvale Steel Company.

After nearly two years of operation, it was reported that no difficulty had been experienced in handling the high-pressure unit. It was not surprising then that the first expansion of the station included two more high-pressure (1,400 psi) boilers with a 10,000-kw high-pressure turbine and a 65,000 kw "normal pressure" (350 psi) main generating unit.

Other electric utilities across the country watched the Weymouth operation with interest, and higher pressures eventually became the norm. In 1930 Edgar Station was the largest tidewater electric plant in the East and by 1970 it was closed. The station was named a National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark by ASME in 1976.

Moultrop was born in Marlborough, Mass., in July of 1865. This engineer led a normal if not, modern life. He married Zaidee Abbie Hopkin in at her parent’s home on Trenton Street in Melrose in 1888, vacationed in Glouster and golfed at local Bellevue Golf Club, explained Rebecca Blumenthal, a commissioner of the Melrose Historical Commission.

His early married life began in Melrose on Chester Street. He was an active member and officer of the Melrose Club, where he participated in bowling and billiard tournaments, Blumenthal explained. He lived in Melrose for at least a decade and began working for Edison Electric in 1892. By 1907 he was living in Dorchester, Mass.

All the cities Irving Moultrop lived in were “commuter suburbs,” Blumenthal explained. And getting to Boston was easy by train. According to Blumenthal, Moultrop worked with Boston Edison as chief draftsman, mechanical engineer, assistant superintendent of construction bureau, chief engineer of the company, and superintendent of construction bureau. He retired from Boston Edison in 1935 and continued consulting for the company in his retirement.

Notably, during World War II he served as a consultant to the Engineering Corps of the Army. He also worked on the construction of numerous smokeless powder plants and on the construction of the Pentagon Building. Honors and memberships include holding the office of vice president of ASME and was named a Fellow of the Society. He was honored with an honorary degree of mechanical engineering from Stevens Institute of Technology in 1931 and founded and served as president of the Engineers Club of Boston.

Cathy Cecere is membership content program manager.

Reliable and efficient, Edgar Station used high-pressure steam to generate electricity. It not only managed to push the envelope of how we thought about how much pressure can be reached “safely” with conventional materials but also established a new record for economy by producing one kilowatt hour of electricity from each pound of coal.

Improving electric generation

The story of the Edgar Station began in the early 1920s when the Boston Edison Company—then known as the Edison Electric Illuminating Company of Boston—acquired land on the banks of the Fore River in Weymouth, Mass. The property included a deep-water harbor that could handle large coal barges and also provide an inexhaustible supply of water for circulating through power plant condensers.

The high-pressure unit itself was the first one of its kind operating in the world and the station that housed it got its name from the president of Boston Edison, Charles L. Edgar, an electrical engineer who studied under Thomas Alva Edison. But at the center of the project was the assistant superintendent of the construction bureau of Edison Electric, Irving Edwin Moultrop.

At the time of this project Moultrop was in his early 50s and had already enjoyed a career in engineering that spanned decades beginning right after he graduated from Framingham High School and began working for the Whittier Machine Co. in Roxbury. The story of how this engineer, active in work of the ASME Boiler Code Committee, guided his company and the electric utility industry toward the higher-pressure range of 1,200 psi steam is historical.

At that time, steam pressures used to generate electricity ranged in the neighborhood of 300 psi, and the first plant for 500 psi was reportedly in early stages of design. Moreover, it would be some time before the development of molybdenum and, later, chrome-molybdenum alloys that would permit raising steam temperature appreciably.

But there were materials available then that could be used at higher pressures if someone would take the necessary initiative. It was Moultrop, leading the project completed by a team of engineers from the Boston firm Stone & Webster, which took a giant step forward and took the electric utility industry into the higher steam pressure range of 1,200 psi.

After studying the gains in efficiency to be had from higher steam pressures and temperatures, and confined by the limits of then available commercial equipment, it was decided to include in the original development at Weymouth only one 1,200 psi boiler and turbine unit, in conjunction with a 350 psi system (three 350 psi boilers supplying steam at 700 °F to a header feeding steam to two 350 psi turbines).

More for You: The Beauty and Genius of the Fairmount Water Works

The high-pressure steam at 1,200 psi and 700 °F expanded down to 375 psi and 500 °F in the General Electric high-pressure turbine, rated at 3,150 kw. Exhaust steam from this turbine returned to the boiler for reheat to 700 °F, then was discharged to the 350 psi header for supplying the "normal pressure" (350 psi) turbines for expansion to one inch Hg absolute. The two 350 psi turbines were each rated 32,000 kw.

The 1,200-psi steam boiler itself was a modification of the conventional Babcock & Wilcox cross drum type. Its heating surface consisted of two-inch tubes, 15 feet long, arranged in three passes. The drum, a solid steel forging 32 feet long, four feet in diameter, and with walls four inches thick, came from the gun works of the Midvale Steel Company.

After nearly two years of operation, it was reported that no difficulty had been experienced in handling the high-pressure unit. It was not surprising then that the first expansion of the station included two more high-pressure (1,400 psi) boilers with a 10,000-kw high-pressure turbine and a 65,000 kw "normal pressure" (350 psi) main generating unit.

Other electric utilities across the country watched the Weymouth operation with interest, and higher pressures eventually became the norm. In 1930 Edgar Station was the largest tidewater electric plant in the East and by 1970 it was closed. The station was named a National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark by ASME in 1976.

Modern engineer story

Moultrop was born in Marlborough, Mass., in July of 1865. This engineer led a normal if not, modern life. He married Zaidee Abbie Hopkin in at her parent’s home on Trenton Street in Melrose in 1888, vacationed in Glouster and golfed at local Bellevue Golf Club, explained Rebecca Blumenthal, a commissioner of the Melrose Historical Commission.

His early married life began in Melrose on Chester Street. He was an active member and officer of the Melrose Club, where he participated in bowling and billiard tournaments, Blumenthal explained. He lived in Melrose for at least a decade and began working for Edison Electric in 1892. By 1907 he was living in Dorchester, Mass.

All the cities Irving Moultrop lived in were “commuter suburbs,” Blumenthal explained. And getting to Boston was easy by train. According to Blumenthal, Moultrop worked with Boston Edison as chief draftsman, mechanical engineer, assistant superintendent of construction bureau, chief engineer of the company, and superintendent of construction bureau. He retired from Boston Edison in 1935 and continued consulting for the company in his retirement.

Notably, during World War II he served as a consultant to the Engineering Corps of the Army. He also worked on the construction of numerous smokeless powder plants and on the construction of the Pentagon Building. Honors and memberships include holding the office of vice president of ASME and was named a Fellow of the Society. He was honored with an honorary degree of mechanical engineering from Stevens Institute of Technology in 1931 and founded and served as president of the Engineers Club of Boston.

Cathy Cecere is membership content program manager.