5 Fantastic Technologies That We Still Don’t Have

5 Fantastic Technologies That We Still Don’t Have

It isn’t just the flying car. Some longstanding tropes of 20th century science fiction are still on the launch pad.

These days, when people refer to the tech sector, they generally refer to consumer electronics and social media such as Facebook and Twitter/X. While that tech has its charms, for some, high tech used to mean the sort of machines once common in science fiction books and movies. The venture capitalist Peter Thiel famously decried the absence of that sort of futuristic technology in the modern world with a quip: “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.”

While the flying car makes a good shorthand for the vision of the future from a bygone era, there’s a whole suite of technologies that seemed inevitable in the 1960s and 1970s that have either never arrived or not lived up to their promises. Here’s a look at five of them.

Decades of effort have produced workable maglev technology, and there are seven lines in operation today, including four in China. But maglevs never achieved superiority over aircraft or even high-speed conventional trains. It turns out, however, the biggest limit on the speed of trains is not the friction of steel wheels against steel tracks, but wind resistance at high speed and the need to reduce speed in curves along the route to avoid strong lateral acceleration. The record speed for a maglev train (375 miles per hour) is only 17 mph faster than the record for a high-speed conventional train, not enough to make it worth the added expense of the needed infrastructure.

Needless to say, that has proven harder to achieve than originally thought. Over the years, there have been attempts to bring other 3D display technologies to the mass market, whether 3D televisions that required wearing special glasses or virtual-reality headsets (that were also a kind of “special glasses”), but none of them have met widespread success. And none have really achieved the glasses-free simplicity of holograms.

Unfortunately, flying cars as a common means of transportation never really made sense. Unlike land cars, which can break and roll to a stop, aircraft are dangerous if they don’t receive immaculate maintenance. And planes are much more fuel-hungry than automobiles. While a nascent air-taxi industry is working to apply new technology to the concept of small aircraft, with four-to-eight-passenger vehicles designed much like oversized multi-rotor drones, their ride-share business model is a far cry from the idea of flying cars for every household.

While fusion as a proposition is seductive, turning it into a workaday power plant has been fraught with difficulty and expense. ITER, the giant experimental reactor intended to demonstrate the viability of fusion, is years late and billions over budget. Dozens of smaller efforts are at work trying to make a viable fusion reactor by taking advantage of newer materials, more powerful computer models, and innovative designs, but the first commercial fusion power plant is still years away.

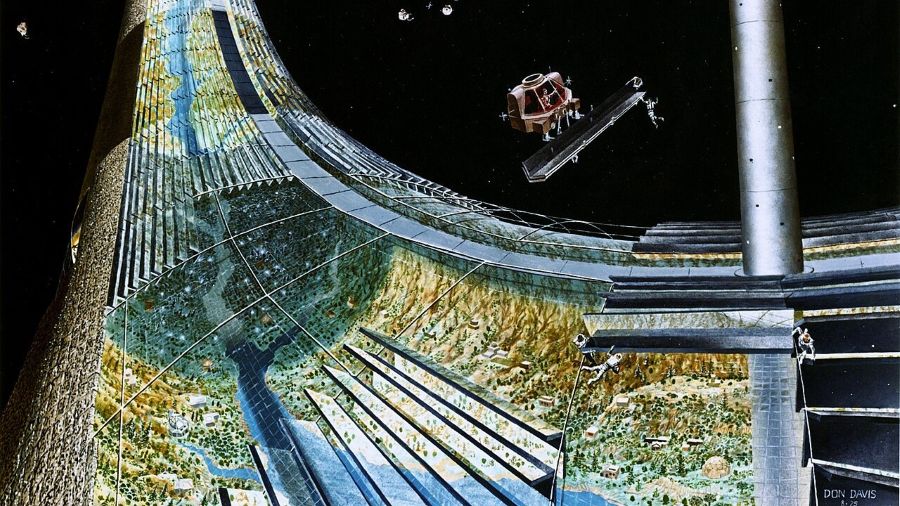

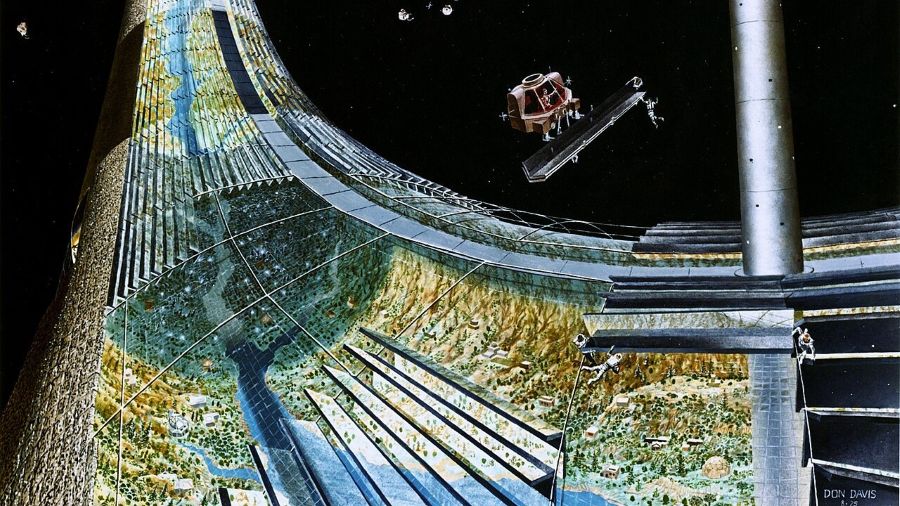

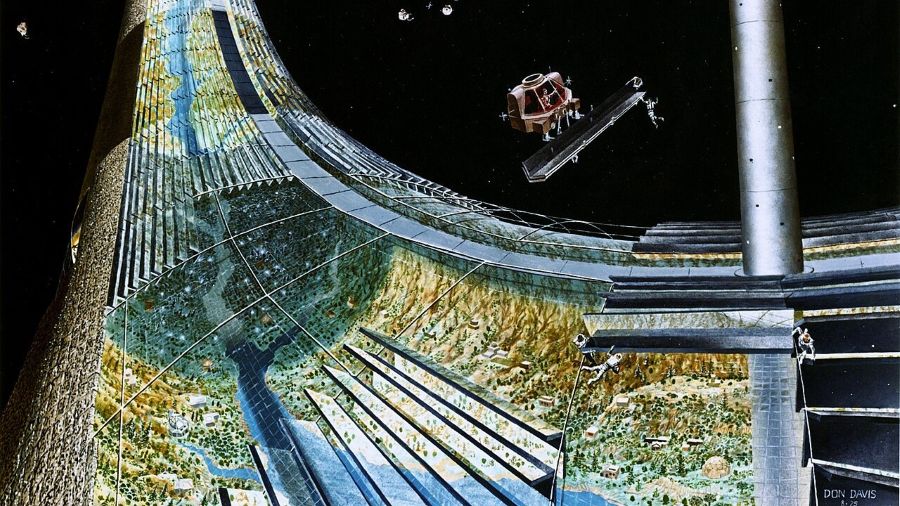

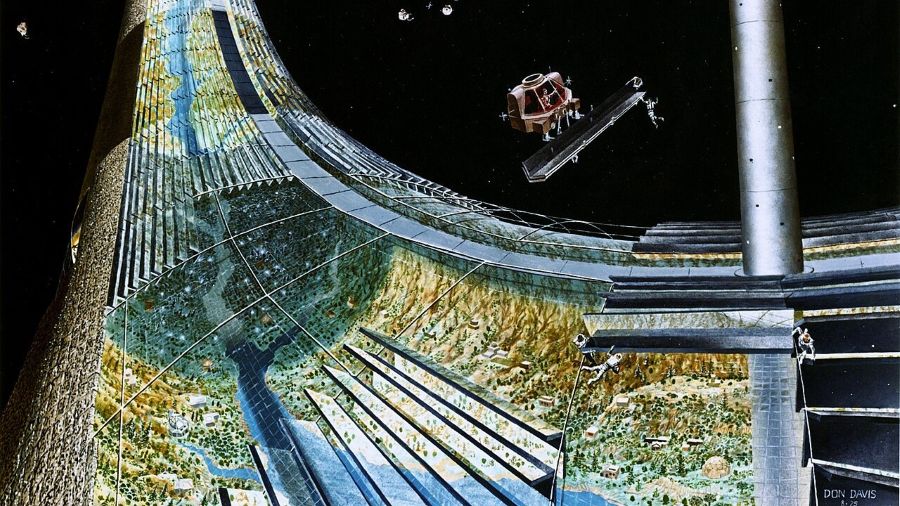

It’s “’25” now and humanity is as far from space settlements as it has ever been. Some of that is due to the slow pace of improvements in spacefaring technologies. But the way the energy industry has transformed in the past 50 years, with whipsaws in the supply and price of oil and the unexpected affordability of terrestrial solar power, undercut the economic imperative for people living in space. It might be neat to live in a 20-mile-long O’Neill cylinder, but no one will pay to build one until they have to.

Jeffrey Winters is a writer in Brooklyn, N.Y.

While the flying car makes a good shorthand for the vision of the future from a bygone era, there’s a whole suite of technologies that seemed inevitable in the 1960s and 1970s that have either never arrived or not lived up to their promises. Here’s a look at five of them.

Maglev trains

At the start of the 20th century, trains were the fastest way to travel. Soon, however, aircraft soared past, largely unencumbered by friction and leaving trains behind on their tracks. Over the course of the century engineers and scientists developed schemes for increasing the speed of trains by eliminating their friction by lifting them from their tracks via magnets. In theory, magnetically levitated trains (maglevs) could travel almost as fast as aircraft and use stations built in city centers rather than remote airports.Decades of effort have produced workable maglev technology, and there are seven lines in operation today, including four in China. But maglevs never achieved superiority over aircraft or even high-speed conventional trains. It turns out, however, the biggest limit on the speed of trains is not the friction of steel wheels against steel tracks, but wind resistance at high speed and the need to reduce speed in curves along the route to avoid strong lateral acceleration. The record speed for a maglev train (375 miles per hour) is only 17 mph faster than the record for a high-speed conventional train, not enough to make it worth the added expense of the needed infrastructure.

Holographic screens

When audio-only radio evolved into flat-picture television in the late 1940s, it seemed like the next logical evolution would be for the images to become three-dimensional. The 3D movie craze of the 1950s were crude attempts at realizing that concept, but in the 1960s advances in holographic technology—which records an interference pattern using laser light so that an image possessing depth and parallax can be recreated later—led many to believe that moving holographic images could be the next step forward in broadcast media.Needless to say, that has proven harder to achieve than originally thought. Over the years, there have been attempts to bring other 3D display technologies to the mass market, whether 3D televisions that required wearing special glasses or virtual-reality headsets (that were also a kind of “special glasses”), but none of them have met widespread success. And none have really achieved the glasses-free simplicity of holograms.

Flying cars

When aircraft first took to the skies in the early 20th century, they weren’t that much more complicated than the automobiles of the era. So it made sense to project that they would follow the same path as cars, and become simple enough, reliable enough, and cheap enough to wind up in every suburban garage. By the 1960s, the futuristic Jetson family on TV had a bubbletop flying car that didn’t look that much different from the land yachts of that era.Unfortunately, flying cars as a common means of transportation never really made sense. Unlike land cars, which can break and roll to a stop, aircraft are dangerous if they don’t receive immaculate maintenance. And planes are much more fuel-hungry than automobiles. While a nascent air-taxi industry is working to apply new technology to the concept of small aircraft, with four-to-eight-passenger vehicles designed much like oversized multi-rotor drones, their ride-share business model is a far cry from the idea of flying cars for every household.

Nuclear fusion

The promise of fusion power is obvious: Fusion reactors could turn a component of ordinary seawater into pollution-free power. Not only is the fuel readily available, but there’s enough on tap to run human civilization for tens of billions of years. That vision has led generations of physicists and engineers to pursue the dream of fusion and build increasingly powerful experimental reactors to perfect it.While fusion as a proposition is seductive, turning it into a workaday power plant has been fraught with difficulty and expense. ITER, the giant experimental reactor intended to demonstrate the viability of fusion, is years late and billions over budget. Dozens of smaller efforts are at work trying to make a viable fusion reactor by taking advantage of newer materials, more powerful computer models, and innovative designs, but the first commercial fusion power plant is still years away.

Orbiting cities

When the afterglow of the Apollo moon landings was still bright, scientists and engineers proposed an entire scheme for permanent human settlements in orbit. The thinking was that human workers in space could build vast solar power collectors that would beam electricity (in the form of microwaves) to earth; at night, they would return to miles-wide space stations that would rotate to produce artificial gravity. The slogan, which combined the orbital position of the proposed settlements with the bravado of 1970s futurists, was “L5 by ’95.”It’s “’25” now and humanity is as far from space settlements as it has ever been. Some of that is due to the slow pace of improvements in spacefaring technologies. But the way the energy industry has transformed in the past 50 years, with whipsaws in the supply and price of oil and the unexpected affordability of terrestrial solar power, undercut the economic imperative for people living in space. It might be neat to live in a 20-mile-long O’Neill cylinder, but no one will pay to build one until they have to.

Jeffrey Winters is a writer in Brooklyn, N.Y.