5 Ballparks That Moved

5 Ballparks That Moved

Multipurpose stadiums transform to meet the needs of several sports. Discover some of the engineering behind these flexible ballparks.

Every spring, baseball fans return to the ballpark to cheer on their favorite teams. While all the top teams in U.S. or Japanese baseball have stadiums to call their own, there was a time when ballparks were expected to meet the needs of multiple sports, especially American football and soccer. Because of the differences in the fields needed for each sport, fitting them in the same ballpark required engineering stadiums that teams could reconfigure as needed.

Here's a look at five stadiums that used innovative methods to accommodate multiple sports in a single ballpark.

The Astrodome in Houston changed all that. Not only was it the first domed stadium, but it was one of the earliest examples of what was eventually called a “cookie cutter” stadium. The middle and upper decks of the seating were fixed in place, but the stands nearest the field rested on rollers. To convert the lower deck from the V-shaped baseball configuration to the parallel one needed for football, the decks rolled into place. In the 1960s and 1970s, many new baseball stadiums adopted the concept, involving either moveable or retractable stands.

Instead, engineers adapted a technology developed by NASA: Air flotation. Under each section was a series of doughnut-like diaphragms; when inflated, the diaphragms lifted the sections by an inch, and compressed air fed through the center of the doughnut bled out the bottom to enable the stands to float. Due to reduced friction, it took only 3,500 pounds of force to move each stand, which a single operator could complete in only 30 minutes.

In spite of this ingenious technology, Aloha Stadium could never attract a major-league baseball or football team.

During baseball season, when a minor-league team played, the eastern stands needed to move out of the way. That single-piece structure weighed 4,000 tons. Engineers developed a water-bearing system similar to the air bearings used at Aloha Stadium. Water pumped through the bearings created a film one-third of an inch thick. Then, hydraulic rams slowly moved the stadium section. It took about six hours to convert the stadium from football to baseball.

When the SkyDome was built in Toronto in the 1980s, engineers solved that problem by constructing a roof that could open. The roof is made up of three large moveable sections and one fixed section. Two sections extend telescopically out from over the fixed section to cover the middle part of the field and a third semicircular section rotates out to cover the far end. Each section moves by electric train motors running over rails. While the roof is huge—more than 345,000 square feet—it is relatively lightweight due to it being made of steel trusses covered with plastic film.

Ironically, because of fears the mechanical components might fail due to cold temperatures, the dome is opened only when the weather is fair and warm.

That conflict was resolved in Sapporo, Japan, by building a multipurpose domed stadium that featured two separate playing surfaces. When the Sapporo Dome hosts the Hokkaido Nippon-Ham Fighters baseball team, they play on artificial turf. To convert the stadium for professional soccer, a set of stands flips up and an enormous tray holding an entire grass soccer field slides in.

Jeffrey Winters is editor in chief of Mechanical Engineering magazine.

Here's a look at five stadiums that used innovative methods to accommodate multiple sports in a single ballpark.

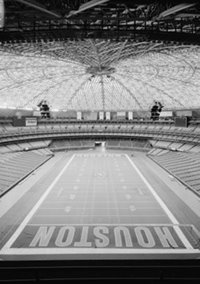

Astrodome

In the 1940s and 1950s, many professional football teams rented out baseball stadiums for their games. Because the rectangular football gridiron sits awkwardly in the fan-shaped baseball field, either the football game was held far away from the fans or temporary bleachers had to be erected before each game.The Astrodome in Houston changed all that. Not only was it the first domed stadium, but it was one of the earliest examples of what was eventually called a “cookie cutter” stadium. The middle and upper decks of the seating were fixed in place, but the stands nearest the field rested on rollers. To convert the lower deck from the V-shaped baseball configuration to the parallel one needed for football, the decks rolled into place. In the 1960s and 1970s, many new baseball stadiums adopted the concept, involving either moveable or retractable stands.

Aloha Stadium

The wheels under most moveable stands could support only relatively light weight, meaning only a small portion of a cookie-cutter stadium would move. The planners of Aloha Stadium in Hawaii wanted something more elaborate. The stadium was designed with four 1,600-ton sections that would swing back and forth like gates to convert the structure from a football to baseball configuration. The challenge was that the sections were too heavy to move on rails.Instead, engineers adapted a technology developed by NASA: Air flotation. Under each section was a series of doughnut-like diaphragms; when inflated, the diaphragms lifted the sections by an inch, and compressed air fed through the center of the doughnut bled out the bottom to enable the stands to float. Due to reduced friction, it took only 3,500 pounds of force to move each stand, which a single operator could complete in only 30 minutes.

In spite of this ingenious technology, Aloha Stadium could never attract a major-league baseball or football team.

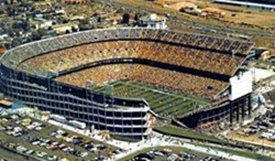

Mile High Stadium

Mile High Stadium in Denver was built for baseball, but while the city waited for its major-league team, the Broncos football team became a hot ticket. To better accommodate football fans, stadium owners built a large stand on the eastern side of the field to complete a horseshoe around the field.During baseball season, when a minor-league team played, the eastern stands needed to move out of the way. That single-piece structure weighed 4,000 tons. Engineers developed a water-bearing system similar to the air bearings used at Aloha Stadium. Water pumped through the bearings created a film one-third of an inch thick. Then, hydraulic rams slowly moved the stadium section. It took about six hours to convert the stadium from football to baseball.

SkyDome

It isn’t only the playing field that’s the difference between baseball and football. Playing conditions are different as well. While football can be played in the rain and snow, inclement weather can cancel a baseball game.When the SkyDome was built in Toronto in the 1980s, engineers solved that problem by constructing a roof that could open. The roof is made up of three large moveable sections and one fixed section. Two sections extend telescopically out from over the fixed section to cover the middle part of the field and a third semicircular section rotates out to cover the far end. Each section moves by electric train motors running over rails. While the roof is huge—more than 345,000 square feet—it is relatively lightweight due to it being made of steel trusses covered with plastic film.

Ironically, because of fears the mechanical components might fail due to cold temperatures, the dome is opened only when the weather is fair and warm.

Sapporo Dome

One point of conflict between baseball teams and the football and soccer teams they share facilities with is the condition of the field. A football game played in muddy conditions can leave a field scarred for weeks. And while baseball teams in Japan and the U.S. play on artificial turf, top-level soccer demands natural grass surfaces.That conflict was resolved in Sapporo, Japan, by building a multipurpose domed stadium that featured two separate playing surfaces. When the Sapporo Dome hosts the Hokkaido Nippon-Ham Fighters baseball team, they play on artificial turf. To convert the stadium for professional soccer, a set of stands flips up and an enormous tray holding an entire grass soccer field slides in.

Jeffrey Winters is editor in chief of Mechanical Engineering magazine.