To Build a Beehive

To Build a Beehive

Engineers want to believe that if you build a better mousetrap, the world will beat a path to your door. Thanks to the Internet, the world now brings cash to jumpstart your business.

That’s the experience of Stuart and Cedar Anderson, a father-and-son team from rural Australia. Via the crowd-funding site Indiegogo.com, they secured $12.5 million for a new type of beehive, one that enables beekeepers to extract honey through a tap without getting stung or upsetting the bees.

Stuart Anderson, a former social worker, started a back-to-the-earth community outside Byron Bay, a town best known for surfing. Cedar, a 35-year-old musician, grew up there without TV or even a normal electrical connection.

Both Andersons were beekeepers and backyard engineers. Stuart acted as the neighborhood’s handyman. Cedar pulled apart abandoned cars (they were that far into the hills) and made musical instruments from their horns. About 10 years ago, after his brother was badly stung, Cedar began looking for a better way to extract honey from a hive.

For the past 150 years, beekeepers had kept bees in boxes that held frames where the insects built their honeycombs. To remove honey, beekeepers donned protective suits, sedated the bees with smoke, and pulled out the frames. After cutting wax caps off the honeycombs, they put the frames in a spinner, extracted the honey, and returned the frame to the hive.

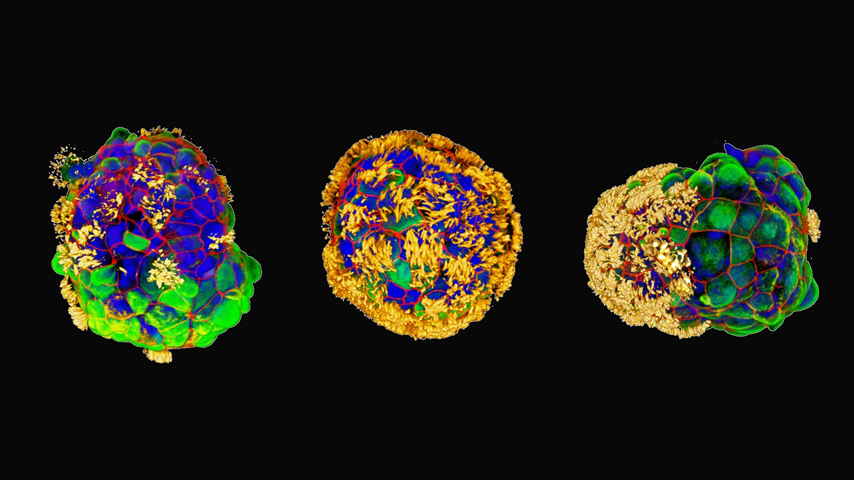

Cedar wanted to simplify the process, but was stuck for years trying to figure out how to remove honey from the frame’s hexagonal cells. He eventually hit upon the idea of shape-changing cells. In the Andersons’ Flow Hive, each frame consists of rows of plastic cells with gaps at the top and bottom of each hexagon. Bees complete the hexagon by patching those gaps with wax. They then fill the cells with honey.

When it comes time to harvest, the beekeeper inserts a crank. Turning it lifts one side of each row of hexagons. This cracks the beeswax used to complete the cell and turns the hexagons into a zigzag channel that runs from the top of the frame to the bottom.

Honey flows down the channel, into a trough, and out a tap at the bottom. Reversing the crank realigns the hexagons, allowing the bees to chew out the wax cap and begin depositing honey again.

Beekeepers do not open the hive, so they are less likely to get stung. The bees remain undisturbed, and may not even realize that the fruits of their labor are being siphoned away, Cedar said.

Of course, not everyone thought it was so easy. If social media made Flow Hive a success, it also brought a wave of criticism. Some beekeepers complained that its very simplicity might reduce beekeeping to a mechanical process and promote poor practices that create health issues for nearby hives. Others fretted that it would encourage people to exploit bees instead of living with them in harmony.

The Andersons reacted by listening. Their Facebook page encourages their more than 200,000 friends to join local beekeeping clubs and learn more about bee health and safety.

In the meantime, though, the father and son are as busy as bees trying to keep up with demand.

Beekeepers do not open the hive, so they are less likely to get stung. The bees remain undisturbed, and may not even realize that the fruits of their labor are being siphoned away.