Ancient Awl Rewrites History

Ancient Awl Rewrites History

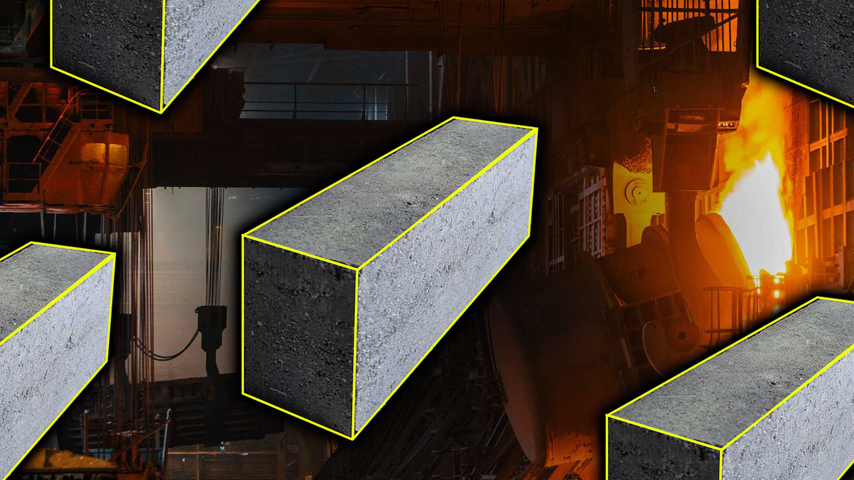

A 7,000-year-old copper artifact discovered in Israel sheds new light on the birth of metallurgy. Image: University of Haifa

A corroded scrap of copper has rewritten the history of technology in the Middle East. It also sheds light on very early trade practices.

According to a recent paper, the artifact is a copper awl, and it was found in a grave at Tel Tsaf in the Jordan Valley of Israel, about 25 miles south of the Sea of Galilee. Calibrated carbon dating places the grave in the late sixth millennium or early fifth millennium B.C.E.

The awl came to light in 2007 during an excavation conducted by Yosef Garfinkel of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The published results were co-authored by Garfinkel, Danny Rosenberg, the head of the Laboratory for Ground-stone Tools Research in the University of Haifa’s Zinman Institute of Archaeology, Florian Klimscha of the German Archaeological Institute in Berlin, which is conducting the renewed project at Tel Tsaf, and Sariel Shalev of the Department of Archaeology at the University of Haifa, who conducted the chemical analysis of the awl.

The corroded item was analyzed by PXRF, a technique for chemical compositional measurement in which X-rays of a known energy are directed towards a target or sample, causing the atoms within the material to emit “fluorescent” X-rays at energies characteristic of its elemental composition.

Rosenberg said that “until this unique find was discovered, the oldest evidence of metallurgy in the region was several centuries younger, dating from the last quarter of the fifth millennium B.C.E and thus we have a unique opportunity to study the very early roots of this advanced technology and how it was introduced to this area.”

Chemical examination of the metal suggests it may have come from the Caucasus, more than 600 miles away. According to Rosenberg and Klimscha, “While the long-distance commercial ties maintained by village communities in our region were already known from even earlier periods, the import of a new technology combined with the processing of a new raw material coming from such a distant location is unique to Tel Tsaf and provides additional evidence of the importance of this site in the ancient world.”

According to the paper, “The Beginning of Metallurgy in the Southern Levant,” published in the journal, PLOS One, Tel Tsaf was an extremely wealthy community for its time. The site has the remains of complexes and buildings, and the scale of its grain silos was unprecedented in the ancient Middle East.

According to the authors, it is possible that metallurgy was first diffused to the southern Levant through exchange networks and only centuries later involved local production. This copper awl, the earliest metal artifact found in the southern Levant, indicates that later metallurgy in the region developed from a more ancient tradition.

It seems possible that the Tel Tsaf copper awl was the result of smelting and melting, but the poor preservation and heavy corrosion of the object make the chemical analysis difficult to interpret.

The copper awl was found among other grave goods that make the grave a very elaborate burial. The grave contained the skeleton of a woman about 40 years old. The burial included a necklace of 1,668 beads made of ostrich egg shell. It is “the most elaborate burial of its period in the entire Levant,” the paper says, and the authors take that as a sign of the prestige value of metal objects at the time.

View the current and past issues of Mechanical Engineering.

Thus we have a unique opportunity to study the very early roots of this advanced technology and how it was introduced to this area.Danny Rosenberg, Zinman Institute of Archaeology, University of Haifa