Human-Powered Submarines Compete

Human-Powered Submarines Compete

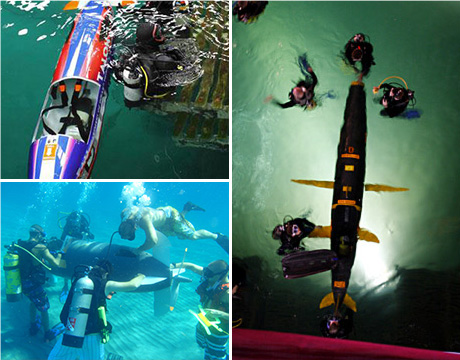

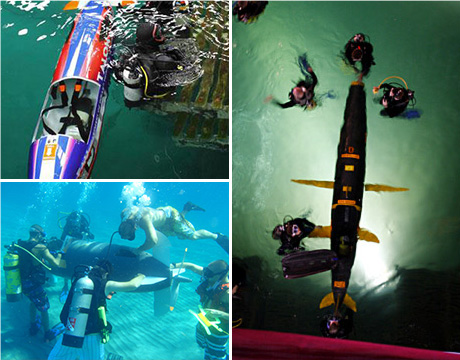

Images: Top & bottom left, HPS, Florida Atlantic University. Right image, ISR.

"Building a submarine is not an everyday thing with easy-to-find answers," says Chris Nunes, in an understatement. But building a human-powered sub is exactly what the Florida Atlantic University ocean engineering major is doing as head mechanical engineer of the university's human-powered submarine club.

He will be a key team member when the sub enters the 12th International Submarine Races (ISR), a biennial competition, scheduled to start June 24 at the Naval Surface Warfare Center's Carderock Division facility in West Bethesda, MD. The ISR program is a competition for engineering students from around the world that involves designing, building, and racing a human-powered submarine.

Team members wear scuba gear and compete in one- and two-person submarines that run submerged along a 100-meter course in the Carderock basin. The ISR began in Florida in 1989 and has been held in Maryland since 1995. Prizes are awarded in a number of categories, including speed, design, best use of composite materials, and innovation.

Nunes, 22, a fourth-year junior scheduled to graduate in 2014, is already a veteran of two competitions and a pilot in both. Describing the last ISR experience as "amazing," he says, "All the teams had very interesting solutions to unique problems. The biggest downfall of the whole race is that the water is freezing cold, a harsh contrast from our normal beach testing n Florida. We came in fastest overall, fastest in our class, second place overall, and got the smooth operator award for our teamwork and reliability."

His second race in England last summer on a u-turn and slalom course was much different from the conventional drag race at ISR. "I did crash while piloting the sub, which led to testing the durability of our fins. It turns out that pourable plastic is stronger than the half-inch aluminum rod that I bent," he explains. "We were able to fix that and come in first in agility and second overall."

Mechanical Challenges

Nunes says the two major mechanical challenges the team faces are corrosion and durability. To overcome these, the team normally uses aluminum, plastic, stainless steel hardware and composite material. If any steel parts, such as the drive gears, are incorporated in the sub design due to cost or for any reason, they are sealed in an air- or oil-filled housing to separate them from the harsh testing environment in the ocean.

Corrosion affects his team more than others because the race is in fresh water, and most teams test in fresh water. Since the university is just minutes from the beach, "We use the space and fight the corrosion," he said. Durability is approached by extensive planning and testing. "Having an ongoing project [means] that if something breaks or is not how we like it, a lot of focus can go into fixing that one system and making the whole product more reliable for the upcoming competition."

For this year's event, the team is not only overhauling its one man sub, called Talon 1, but is also building a new two-man sub.

Applying Skills

Dr. Edgar An, the team's advisor and a professor in the Department of Ocean and Mechanical Engineering, says the team is "incorporating electronics to control the diving electronically." They have to figure out how that works, write the software, and determine what kind of sensors and electronics are needed, he adds. "They have to think of every single aspect."

From his perspective, the most important and difficult tasks are designing a propeller and analyzing system performance.

The Florida Atlantic team is also focused on winning back its title as Guinness World Record holder, a designation that it lost a decade ago.

Even though for core team members, the project takes up more of their time than their actual classroom work, they say it's well worth it. "It's very rewarding to know that I am getting more out of my college tuition than just a degree," Nunes said.

He added, "I have learned everything from 3-D CAD modeling to team skills, [including] fluid dynamics, mechanical intuition, hardware specification, working with fiberglass, coordinating building efforts, communicating more effectively, working within a budget, general problem solving, and mainly the exposure to actually getting things done instead of just doing the math and speculating."

Dr. An says it also gives students an advantage in applying for internships and jobs after graduation.

Aside from all of that, Nunes describes the experience as like nothing else when he is "anxiously floating in the sub at the starting line, waiting to hear the buzzer and the announcer call over the hydrophone, 'Talon 1: Go, go, go.' At that point, you just have to give it all you got and hope all of your hard work holds true until you cross the finish line."

Nancy S. Giges is an independent writer.

Two major mechanical challenges the team faces are corrosion and durability.