Power to the People

Power to the People

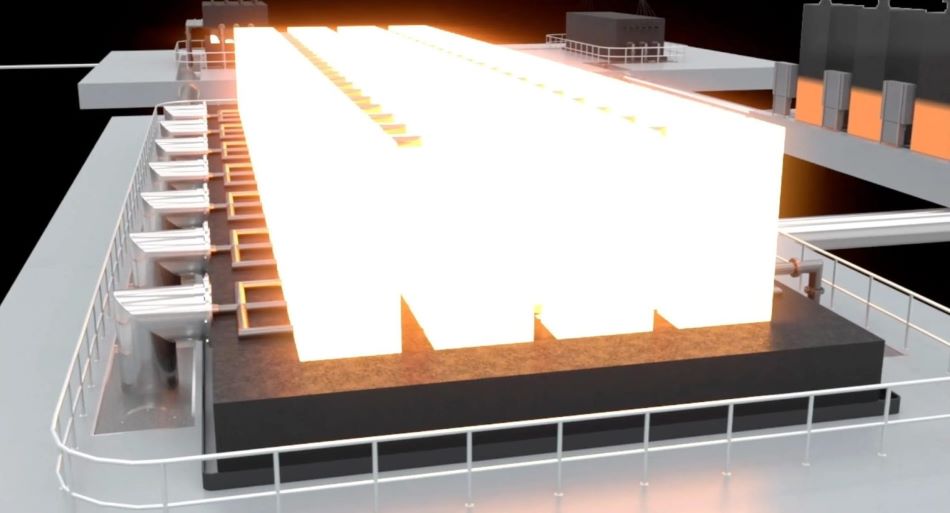

The Rural Electrification Administration (REA) erects power lines in rural areas. Image: U.S. Department of Agriculture / Wikimedia Commons

The 1933-34 Chicago World’s Fair kicked off with an exotic lighting display powered by actual star light. Organizers set up a remote network of photoelectric cells which converted rays from the star Arcturus into electricity and transmitted it to the exposition site. Because that light had taken about 100 years to reach Earth, the gimmick fit the fair’s “Century of Progress” theme to a tee. But only miles outside of Chicago and across vast swaths of America’s isolated rural areas, millions of families were still living as their forebears had 100 years before – in the dark. It would take one rich and powerful man’s astronomical electric bill and one engineer’s unwavering vision to help rural America see the light at last.

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the Rural Electrification Act (REA) and the resulting ambitious and once-controversial federal lending agency launched in May 1936 to extend the benefits of electric power to all Americans. Championed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt as a component of his New Deal policies, the REA provided low-interest five-year loans to locally owned non-profit electric cooperatives to build power lines reaching farms and small communities the large power companies would not go near.

In the mid-1930s, 90% of rural homes were without electricity. Nearly every major population center had been enjoying the utility and the labor-saving machines and appliances that came with it for decades. Electricity brought instantaneous news and entertainment into the homes of a coast-to-coast urban audience, and Hollywood – then at the peak of its golden age – was cranking out new classics every week, further fueling a cultural sophistication gap between Americans with access to these conveniences and those without it. Down on the farm, cows were still milked by hand, water was still fetched from wells, and trips to the outhouse were still part of the routine. If electric companies had the know-how to get power from a star all the way to Chicago, why then couldn’t they also light up rural America?

One answer is money. According to author Felix Rohatyn in his 2009 book Bold Endeavors, the power industry’s focus on profit over people fueled its emphatic resistance to rural electrification. Industry estimates of a $2,000-per-mile investment to extend power lines into a typical rural area, with perhaps as few as one or two homes per mile, would never pencil out. The handful of large utility companies that monopolized the industry simply wrote off millions of people, in Rohatyn’s view.

A Bill Inspired by a Bill

The federal government had been studying the growing urban-rural divide since the administration of the first President Roosevelt, Teddy, whose 1908 Country Life Study sought ways “to make country life as effective and satisfying as big city life.” Electrification was part of that equation, and the study inspired Pennsylvania Governor Gifford Pinchot, who had served Roosevelt as the first head of the U.S. Forestry Bureau, to explore rural electrification in his state. His pick to run the project was Lehigh University-trained mechanical engineer Morris Cooke, who proposed construction of power plants near coal mines and a rural network of public transmission lines. The plan was rejected, but it caught the attention of the governor of neighboring New York state, Franklin Roosevelt.

Years earlier, FDR got a first-hand taste of rural America’s electric-power woes. His remote but beloved Warm Springs, Georgia, cottage had been equipped with electricity. Yet to his shock and despite his wealth, the future president faced electric bills for the resort home more than four times higher than the cost of electrifying his huge estate in upstate New York. So began his “long study of public utility for electric current and the whole subject of getting electricity into farm homes.” As president, he enlisted Cooke as his close advisor on matters of power and conservation, specifically tasking him with rural electrification projects in the Mississippi River valley and elsewhere. Cooke’s zealous belief in the moral and economic virtues of rural access to electricity give rise to the federal legislation that, after much industry pushback and political compromise, was ratified and signed into law in 1936.

"When we mark the 80th anniversary of the REA, we celebrate the success of a partnership between rural communities and the federal government. Rural electrification changed people's lives and boosted the rural economy. The partnership remains robust today," said Jeffrey Connor, interim CEO of the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association.

Powerful Impact

Within REA’s first two years, 350 new cooperatives brought power to 1.5 million farms in 45 states. By the 1950s, REA reached more than 90% of U.S. farms. The availability of electricity gave rise to 100 new types of machines to automate traditional farm chores and create new efficiencies. Lighting was the most pervasive innovation, and electrical pumps, heaters, chillers and motors give rise to new practices like irrigation, milk collection and processing, egg incubation, and livestock watering. The arrival of electricity in remote homes made domestic life easier for hardworking farming, fishing, logging and mining families. Refrigeration and electrically pumped water gave rise to indoor plumbing and long-term food storage, which had a positive effect on human health. Country families now could tune into the same radio broadcasts their big-city brethren enjoyed. The cultural divide gave way to a melting pot effect as rural traditions such as country music and dance caught on in urban areas.

“It was pretty exciting,” recalled Lionel Youst, 82, a Pacific Northwest historian and author whose boyhood home in the rugged forestlands near Coos Bay, Oregon, was the last house on a rural power line completed in 1940. “It was thefirst house I ever lived in that had electricity. By sticking wires and chains and other objects into the lightsockets I learned very quickly that electricity was nothing to fool around with.” Years later, Youst bought that very house and still lives there today. “I moved back here with the family in 1975 and the same circuit breaker box, black from overheat, was still in use. Why the house didn't burn down nobody will ever know.”

Today, 99 percent of all farms have electric service from co-ops originally kickstarted with REA loans. The program continues today as the Rural Utilities Service within the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“Investments in electric infrastructure have greatlyimproved the quality of life for rural residents and increased farm productivity, making America the breadbasket to the world,” said RUS administrator Brandon McBride. “Since 2009, USDA Rural Development has invested $31.3 billion in 963 electric projects that have financed more than 185,000 miles of transmission and distribution lines serving 4.6 million rural residents.”

Michael MacRae is an independent writer.

Learn about the latest trends in energy solutions at ASME’s Power & Energy Conference and Exhibition.

Rural electrification changed people's lives and boosted the rural economy. The partnership remains robust today.Jeffrey Connor, Interim CEO, NRECA