Self-Driving Boat for the Win

Self-Driving Boat for the Win

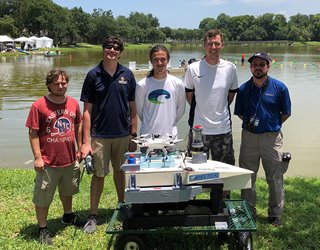

Unmanned boats participating in the RoboBoat competition have to be fully autonomous. Photo: John F. Williams

Unmanned boats have crossed the Atlantic and navigated around Antarctica, but they are very difficult to make fully autonomous.

Undergraduates from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach, Fla., can testify to such. They placed second out of 13 teams in this year’s international RoboBoat competition with an autonomous boat they built from scratch.

“Last year’s team really dropped off the face of the earth,” said Andrew Wood, this year’s team lead. “I volunteered, even though I had not worked on it at all or had any experience in aquatic robotics.”

Wood, the only senior on the team, spent the first weeks of the fall recruiting. “I grabbed as many freshman as I could,” he said. “We really just needed people.”

Once he had gathered a team of ten students, they spent the rest of the first semester learning about aquatic robotics and designing a boat; then, they spent the spring building.

Further Reading: Self-Sailing Boats in the Atlantic

To go from no boat to winning the silver medal, Wood and team looked to the school’s previous participating team’s boat (which placed fourth in 2018) to learn what made it successful. “Things that worked: The big platform on back for landing a quadcopter—a good way for accessing the back of the boat,” Wood said.

Made of foam, however, it was over-buoyant and leaned to one side. Additionally, the thrusters were not efficient.

Embry-Riddle team based its design on combat ships—trimarans, with a main hull and two outriggers. The team built with wood, and corrected other flaws, too. Instead of thrusters at the boat’s stern, students had one at the stern and one in the middle, providing it with power to turn quickly.

Because of the thruster arrangement, the Embry-Riddle boat won the speed challenge at the RoboBoat competition, hands down.

Further Reading: A Robot Crab to Clean the Ocean

The self-driving boat performed well in other events, too, including a “find the path” challenge, where boats must thread through a group of buoys surrounding a pole, do a lap around it and return; a “raise the flag” challenge, in which boats’ quadcopters fly over an island—located in the center of a pond—to read a number only visible from above to communicate that number so the boat can dock at a specific station, and then land back on the boat (no team has successfully landed correctly yet); and an autonomous docking challenge, that has boats following a detectable underwater noise that guides them to dock at a precise station (which Embry-Riddle did not attempt this year).

All of these tasks must be accomplished by the boats, autonomously. “From the very beginning of the competition, it is all autonomous. We hit the ‘go’ button, and have to sit back and watch,” Wood said. “The boat has to know when to go into the field, when to launch the quadcopter, and the quadcopter has to take off autonomously.”

Wood is confident that the ingenuity demanded by the competition is not just for sport. Applications exist for any kind of water craft, especially for large ships docking. “Giant shipping vessels coming into port are just massive; the captain can’t see over the edge of the boat. So they rely on tugboats,” Wood said. “If they had quadcopters that could go take a look for them, they wouldn’t need the tugboats. It might be more efficient than using multiple boats that are using fuel.”

Further Reading: Sailing Toward Autonomy: Future of Self-Driving Cargo Ships

The winning team this year came from Indonesia’s Sepuluh Nopember Institute of Technology. Wood believes their boat cost less than the Embry-Riddle, with less advanced sensors, too. Their advantage, however, was a team that had spent years on the boat. With design finished early in the process, they could be more efficient, programming and testing.

Wood has faith that the team he has put together will rise to the top next year. “The plan from the beginning was always to build a four-year team,” he said. “When I grabbed these freshman, I told them this was a project they could own for the next four years. Next year, there will be a much bigger focus on software and sensing. As much as we were able to accomplish this year, no one is starting over. That was our goal this year and I believe we accomplished it.”

Michael Abrams is a technology writer based in Westfield, New Jersey.

Undergraduates from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach, Fla., can testify to such. They placed second out of 13 teams in this year’s international RoboBoat competition with an autonomous boat they built from scratch.

“Last year’s team really dropped off the face of the earth,” said Andrew Wood, this year’s team lead. “I volunteered, even though I had not worked on it at all or had any experience in aquatic robotics.”

Wood, the only senior on the team, spent the first weeks of the fall recruiting. “I grabbed as many freshman as I could,” he said. “We really just needed people.”

Once he had gathered a team of ten students, they spent the rest of the first semester learning about aquatic robotics and designing a boat; then, they spent the spring building.

Further Reading: Self-Sailing Boats in the Atlantic

To go from no boat to winning the silver medal, Wood and team looked to the school’s previous participating team’s boat (which placed fourth in 2018) to learn what made it successful. “Things that worked: The big platform on back for landing a quadcopter—a good way for accessing the back of the boat,” Wood said.

Made of foam, however, it was over-buoyant and leaned to one side. Additionally, the thrusters were not efficient.

Embry-Riddle team based its design on combat ships—trimarans, with a main hull and two outriggers. The team built with wood, and corrected other flaws, too. Instead of thrusters at the boat’s stern, students had one at the stern and one in the middle, providing it with power to turn quickly.

Because of the thruster arrangement, the Embry-Riddle boat won the speed challenge at the RoboBoat competition, hands down.

Further Reading: A Robot Crab to Clean the Ocean

The self-driving boat performed well in other events, too, including a “find the path” challenge, where boats must thread through a group of buoys surrounding a pole, do a lap around it and return; a “raise the flag” challenge, in which boats’ quadcopters fly over an island—located in the center of a pond—to read a number only visible from above to communicate that number so the boat can dock at a specific station, and then land back on the boat (no team has successfully landed correctly yet); and an autonomous docking challenge, that has boats following a detectable underwater noise that guides them to dock at a precise station (which Embry-Riddle did not attempt this year).

All of these tasks must be accomplished by the boats, autonomously. “From the very beginning of the competition, it is all autonomous. We hit the ‘go’ button, and have to sit back and watch,” Wood said. “The boat has to know when to go into the field, when to launch the quadcopter, and the quadcopter has to take off autonomously.”

Wood is confident that the ingenuity demanded by the competition is not just for sport. Applications exist for any kind of water craft, especially for large ships docking. “Giant shipping vessels coming into port are just massive; the captain can’t see over the edge of the boat. So they rely on tugboats,” Wood said. “If they had quadcopters that could go take a look for them, they wouldn’t need the tugboats. It might be more efficient than using multiple boats that are using fuel.”

Further Reading: Sailing Toward Autonomy: Future of Self-Driving Cargo Ships

The winning team this year came from Indonesia’s Sepuluh Nopember Institute of Technology. Wood believes their boat cost less than the Embry-Riddle, with less advanced sensors, too. Their advantage, however, was a team that had spent years on the boat. With design finished early in the process, they could be more efficient, programming and testing.

Wood has faith that the team he has put together will rise to the top next year. “The plan from the beginning was always to build a four-year team,” he said. “When I grabbed these freshman, I told them this was a project they could own for the next four years. Next year, there will be a much bigger focus on software and sensing. As much as we were able to accomplish this year, no one is starting over. That was our goal this year and I believe we accomplished it.”

Michael Abrams is a technology writer based in Westfield, New Jersey.