How Mechanical Engineers Raise Venture Capital

How Mechanical Engineers Raise Venture Capital

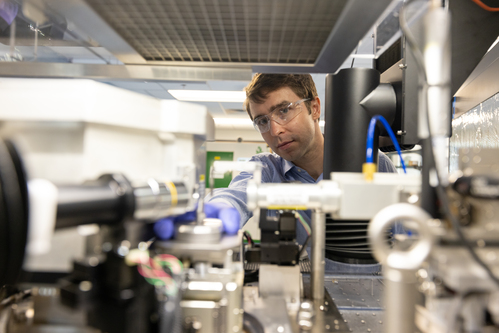

To fund its “rocktoon” balloon-based rocket launch system to send minisatellites into orbit, Leo Aerospace turned to family, friends, contests, and crowdsourcing. Image: Leo Aerospace Corp.

A rocket launched from a high-altitude balloon. A robotic welder for small factories. A zero-emissions electric bus. A machine that thins out weak plants.

Mechanical engineers invented all these devices, but they needed to raise venture capital to turn them into tangible products.

It is not an easy path, even in a market where VC investments recently broke $100 billion for the first time since the height of the dot-com boom in 2000. Yet most funding went toward pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, software, and healthcare services and systems.

Mechanical innovations are way down on that list. In fact, most of the engineers interviewed for this story said VCs were reluctant to fund hardware companies. A 2013 MIT study, Production in the Innovation Economy, agreed. It found investors were often daunted by the time and capital it took to develop and manufacture hardware products.

Still, mechanical engineers should take heart. Venture capitalists are softening their stance on hardware.

One reason, according to a 2018 report from the National Venture Capital Association, is that investors want to fund startups that are applying machine learning, computer vision, robotics, and other emerging technologies to manufacturing. In fact, one of 2018’s largest first-round (Series A) deals was for $179 million for Bright Machines, a software automation company that does exactly that.

Surprisingly, 3D printing has also helped, said Sven Strohband, a partner with Khosla Ventures, a Silicon Valley VC firm founded by Vinod Khosla, co-founder of Sun Microsystems and former mechanical engineer.

“We can make things that look very close to the end product relatively rapidly for not quite a lot of money,” he said. “So, we can push products or samples into the market way earlier now than before.”

Still, it takes a special engineer to score with VCs.

Many of the co-founders we spoke with met at universities with strong entrepreneurship programs. There, they discovered and tested their ideas, and some even met their first investors.

They did not just show up at VC offices. First, they raised money from research grants, business competitions, government contracts—as well as friends, family, and even potential customers. This enabled them to build prototypes that made their ideas seem less risky to potential investors.

They were also flexible. One company started off with an idea for an autonomous lawnmower, but pivoted to a smart pesticide sprayer. Another started a consulting company to figure out what they should build. Another started with natural gas buses but switched to electric vehicles.

These are their stories.

Leo Aerospace Corp., Gardena, Calif.

Stage: Seeking seed financing

Leo Aerospace is aiming for space but needs venture capital to get there.

Mechanical engineer Dane Rudy and four Purdue University classmates launched the company in 2017. Their goal was to make microsatellite launches cheaper, easier, and more sustainable by launching small rockets from reusable high-altitude balloons.

The team, which includes aerospace and industrial engineers, did not start out with that vision. Instead, while in Purdue’s entrepreneurship program, aided by $52,500 in National Science Foundation grants, they researched different markets, and uncovered an emerging industry with a problem.

The space industry was set up to use large rockets to put large satellites into orbit, Rudy explained. Microsatellite owners must scramble to find extra room on those rockets. This delays flight schedules and forces compromises in optimal orbits. Leo designed its rocket-and-balloon solution to launch small payloads into orbit on the cheap.

To launch itself, Leo raised about $30,000 (and engineering software licenses) by winning startup competitions at Purdue and West Coast venues.

To find more money—and mentoring—they started investigating accelerator programs. Most U.S. accelerators focused primarily on software. But Australia’s Startmate focused on hardware, and one of its VC partners focused on aerospace.

Australia also had another advantage. “Our business plan is reinforced by the ability to launch frequently, and that is very difficult to do with the air traffic in the United States,” Rudy said. “Australia provides a unique opportunity to launch more frequently and with less policy and regulatory pressure.”

At Startmate, the engineers designed and 3D-printed components for its system over several three-month campaigns. VC partners provided Leo with $50,000, and helped them practice and refine their pitch to raise capital.

You May Also Like: The State of American Manufacturing 2019

Those partners also taught Leo’s founders a critical lesson: Get payment commitments from the 170 potential customers they had interviewed while researching potential markets for their company. Those letters of intent gave Leo credibility with potential investors.

To raise larger sums, potential investors needed to see a prototype that lowered their perceived risk. To build it, Leo needed to hire experienced engineers who could manage a development cycle.

To raise it, the recent graduates launched a fundraising campaign on Netcapital, a crowdfunding platform. This raised $220,000, primarily from friends, family, and some angel investors.

“We chose to go with equity-based crowd funding because we needed a decent amount of money to conduct hardware testing,” Rudy said. “We also wanted to be able to control how much of the company we were giving away [to the investors].”

The campaign provided the funds to successfully launch a rocket in December 2018 from a reusable balloon platform in the Mojave Desert. Leo was the first company the Federal Aviation Administration ever authorized for such a launch, Rudy said.

The company recently raised another $90,000 from internal venture capital sources at Plug and Play, a Silicon Valley accelerator. Now that they have demonstrated the system and lined up potential customers, the co-founders are working with outside advisors to raise $8 million in seed financing.

Path Robotics Inc., Cleveland, Ohio

Stage: Series A Funding

Most engineers develop a technology and then try to find a market for it. Brothers Andrew and Alex Lonsberry reverse-engineered the process.

The second-generation mechanical engineers started Path Robotics in 2014 as an engineering consultancy in Ohio. They already knew about robotics and machine learning. Their goal was to find customers and then build a system around their unanswered needs.

“You need to search and search to find that perfect market that exploits the technology you have,” Path CEO Andrew Lonsberry said. “It has to be big enough to get the interest of venture capitalists and [one that can] really grow.”

The brothers found their market when a customer said that small-to-medium-sized manufacturers faced a shortage of skilled welders, but robotic welding systems were geared for larger companies with a dedicated programming and support staff. He needed something smaller, cheaper, and easier to use.

Building two prototypes drew down Path’s cash. To raise venture capital, they queried former lab and classmates, other startups, and friends in Silicon Valley for ideas and introductions.

The answers were not encouraging.

“Early on, we were told that Silicon Valley venture capitalists like to fund startups in the Valley, with founders from the Valley, who’ve had experience working in the Valley,” Chief Technology Officer Alex Lonsberry said. “Anything hardware-related was too risky.”

The brothers ignored those warnings and travelled to California to meet with VCs who funded hardware companies. First, though, they practiced their pitch on friend and fellow mechanical engineer Lee Redden, co-founder of agriculture technology company Blue River Technology.

It was a good thing they did. He sharply critiqued their pitch. In response, they changed how they described their target market and their research so that it would be more meaningful to investors, the brothers said.

It worked.

Despite an “incredibly intimidating” introductory meeting with hardware VC Lemnos and their refusal to move to California, they scored a second meeting. The Lemnos partner then introduced them to 25 other firms.

Their efforts raised $2.5 million in seed round financing from lead investors Lemnos and Basis Set Ventures, another Valley VC, and six other firms.

Two months later—extremely unusual in the VC world—the brothers secured another $12.5 million in Series A funding through lead investor Drive Capital of Cleveland and Basis Set.

Critical to winning with the venture firms were those two working prototypes.

“To have a client that was at best making $20 million annually in revenue willing to shell out hundreds of thousands of dollars to us to make a prototype cell for them because they needed it so bad was a huge step in showing a product market fit,” said Alex.

Proterra Inc., Burlingame, Calif.

Stage: Series 7 Funding

Batteries and venture capital are powering Proterra’s zero-emissions electric buses on streets, highways, and around college campuses.

Electric buses were not on the agenda when founder Dale Hill, a mechanical engineer and a serial entrepreneur, bought a bus company in the early 2000s. It had a Federal Transit Administration contract to build low-emission compressed natural gas buses for Denver’s 16th Street Mall.

The vehicles impressed FTA, and in 2006 the agency offered Hill a grant to build a battery-powered bus prototype.

Hill used the money to reinvent the vehicle. Rather than convert a diesel bus to electric, Hill built his prototype from the ground up. This let him store the 18 ft. x 3.5 ft. x 0.6 ft. battery packs in the floors and between the tires, a safer and more efficient design, he said.

“The only new technology bus that had entered the market in the past 20 to 30 years was the bus we had built for Denver’s 16th Street Mall,” Hill said.

While grants and contracts could fund prototypes, Hill needed venture capital to build a business. He brought on a professional executive with experience attracting investors.

In 2010, Proterra nailed down its first commercial contract, ultimately selling 31 buses to Foothill Transit, a regional transit agency in Pomona, Calif.

Nine months later, the manufacturer used the contract and prototype to pitch investors. One of the nation’s top VCs, Silicon Valley’s Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, led a $30-million investment round.

As mass transportation turned greener across the country, Proterra’s customers grew to include cities, regional transit agencies, universities, and airports. Proterra raised an additional $420 million (excluding debt capital) from VCs between 2014 and 2018 in several funding rounds.

The company also added corporate investors, who helped it ramp up production. In fact, Germany’s Daimler, which makes buses as well as trucks and cars, co-led investors who poured $155 million into the company in 2018. The two companies announced future “synergies,” starting with jointly building electric school buses.

At the time, Proterra had sold more than 675 vehicles in the United States and Canada. It currently claims 60 percent of the North American electric transit market, and is expanding its Greenville, S.C., factory and building a new plant near Los Angeles.

“If you want to see your dream succeed then you have to determine what price you’re willing to pay,” Hill said.

Hill still retains his title of founder, but Kleiner Perkins controls the company and has moved its headquarters to just north of Silicon Valley.

Hill is OK with that. “So many good ideas get 90 percent to the goal line, and the person either runs out of money or gives up, and never gets to see their dream,” he said. “I’ve just been too stubborn to do that.”

Blue River Technology, Sunnyvale, Calif.

Stage: Acquired

Lee Redden and Jorge Heraud’s marriage of agricultural hardware and software became a VC success in 2017, when investors sold the business to Deere & Co. for $305 million for 10 times more than their investments.

The startup began when Redden and Heraud met in a Stanford University entrepreneurship class taught by Steve Blank, a serial entrepreneur and investor.

There, Redden’s mechanical engineering background in robotics and computer science meshed with Heraud’s 14 years at navigation systems leader Trimble, where he led the precision agriculture business unit.

They originally planned to build autonomous lawnmowers, but soon realized this was a dead end.

“The technology had not quite come of age, and it was very expensive,” Redden said.

So they pivoted. The result was See & Spray, a machine that uses computer vision to thin lettuce crops. Lettuce is intentionally overplanted, then thinned by hand. See & Spray does this automatically, detecting and spraying weaker plants with pesticides to prevent overcrowding.

Their instructor, Blank, was impressed enough to invest in seed funding. So did Ulu Ventures, a handful of angel investors, and friends. They raised $250,000, supplemented with substantial National Science Foundation grants.

The money let them rent space, buy equipment, and build a prototype, Redden said. But when they began looking for Series A funding, they met resistance.

“Most were pretty shy on funding things with hardware,” Redden said.

So they pivoted again, emphasizing the value of the data. Their smart system would understand what healthy lettuce—and perhaps other plants—looked like and use that information to thin rows or kill weeds. To minimize concerns, they told VCs that the hardware was “not as major a component” of the business.

Recommended for You: Requiem for Rethink Robotics

“They had a very clever business model,” Clint Korver, Ulu Ventures’ co-founder and managing director, said. “As opposed to selling the technology, they used the technology themselves and just sold the value. They were able to deliver it much better and cheaper than anyone else because of the clever technology they were using.”

In 2012, Khosla Ventures invested $3.1 million in Blue River. This enabled the pair to hire a team to build working prototypes that generated revenue.

With each funding round, Redden and Heraud delivered on key performance financial and technology benchmarks. This built investor confidence.

In 2014 a Series B round netted $10 million to commercialize See & Spray. In 2015, it raised $17 million, including funds from two agrochemical companies that might have wanted to partner with Blue River.

“They are not investing simply based on the financials, but on possible synergy between what you’re doing and what they’re doing,” Redden said.

To prepare for its next round of financing, Blue River pitched Deere & Co. as a potential strategic partner. The two companies found their visions of agriculture’s future aligned, and Redden and Heraud agreed to an acquisition. While they still lead the business they founded, Blue River is now a wholly owned subsidiary of Deere.

Carol Lawrence is a technology writer based in Los Angeles, Calif.

Mechanical engineers invented all these devices, but they needed to raise venture capital to turn them into tangible products.

It is not an easy path, even in a market where VC investments recently broke $100 billion for the first time since the height of the dot-com boom in 2000. Yet most funding went toward pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, software, and healthcare services and systems.

Mechanical innovations are way down on that list. In fact, most of the engineers interviewed for this story said VCs were reluctant to fund hardware companies. A 2013 MIT study, Production in the Innovation Economy, agreed. It found investors were often daunted by the time and capital it took to develop and manufacture hardware products.

Still, mechanical engineers should take heart. Venture capitalists are softening their stance on hardware.

One reason, according to a 2018 report from the National Venture Capital Association, is that investors want to fund startups that are applying machine learning, computer vision, robotics, and other emerging technologies to manufacturing. In fact, one of 2018’s largest first-round (Series A) deals was for $179 million for Bright Machines, a software automation company that does exactly that.

Surprisingly, 3D printing has also helped, said Sven Strohband, a partner with Khosla Ventures, a Silicon Valley VC firm founded by Vinod Khosla, co-founder of Sun Microsystems and former mechanical engineer.

“We can make things that look very close to the end product relatively rapidly for not quite a lot of money,” he said. “So, we can push products or samples into the market way earlier now than before.”

Still, it takes a special engineer to score with VCs.

Many of the co-founders we spoke with met at universities with strong entrepreneurship programs. There, they discovered and tested their ideas, and some even met their first investors.

They did not just show up at VC offices. First, they raised money from research grants, business competitions, government contracts—as well as friends, family, and even potential customers. This enabled them to build prototypes that made their ideas seem less risky to potential investors.

They were also flexible. One company started off with an idea for an autonomous lawnmower, but pivoted to a smart pesticide sprayer. Another started a consulting company to figure out what they should build. Another started with natural gas buses but switched to electric vehicles.

These are their stories.

Leo Aerospace Corp., Gardena, Calif.

Stage: Seeking seed financing

Leo Aerospace is aiming for space but needs venture capital to get there.

Mechanical engineer Dane Rudy and four Purdue University classmates launched the company in 2017. Their goal was to make microsatellite launches cheaper, easier, and more sustainable by launching small rockets from reusable high-altitude balloons.

The team, which includes aerospace and industrial engineers, did not start out with that vision. Instead, while in Purdue’s entrepreneurship program, aided by $52,500 in National Science Foundation grants, they researched different markets, and uncovered an emerging industry with a problem.

The space industry was set up to use large rockets to put large satellites into orbit, Rudy explained. Microsatellite owners must scramble to find extra room on those rockets. This delays flight schedules and forces compromises in optimal orbits. Leo designed its rocket-and-balloon solution to launch small payloads into orbit on the cheap.

To launch itself, Leo raised about $30,000 (and engineering software licenses) by winning startup competitions at Purdue and West Coast venues.

To find more money—and mentoring—they started investigating accelerator programs. Most U.S. accelerators focused primarily on software. But Australia’s Startmate focused on hardware, and one of its VC partners focused on aerospace.

Australia also had another advantage. “Our business plan is reinforced by the ability to launch frequently, and that is very difficult to do with the air traffic in the United States,” Rudy said. “Australia provides a unique opportunity to launch more frequently and with less policy and regulatory pressure.”

At Startmate, the engineers designed and 3D-printed components for its system over several three-month campaigns. VC partners provided Leo with $50,000, and helped them practice and refine their pitch to raise capital.

You May Also Like: The State of American Manufacturing 2019

Those partners also taught Leo’s founders a critical lesson: Get payment commitments from the 170 potential customers they had interviewed while researching potential markets for their company. Those letters of intent gave Leo credibility with potential investors.

To raise larger sums, potential investors needed to see a prototype that lowered their perceived risk. To build it, Leo needed to hire experienced engineers who could manage a development cycle.

To raise it, the recent graduates launched a fundraising campaign on Netcapital, a crowdfunding platform. This raised $220,000, primarily from friends, family, and some angel investors.

“We chose to go with equity-based crowd funding because we needed a decent amount of money to conduct hardware testing,” Rudy said. “We also wanted to be able to control how much of the company we were giving away [to the investors].”

The campaign provided the funds to successfully launch a rocket in December 2018 from a reusable balloon platform in the Mojave Desert. Leo was the first company the Federal Aviation Administration ever authorized for such a launch, Rudy said.

The company recently raised another $90,000 from internal venture capital sources at Plug and Play, a Silicon Valley accelerator. Now that they have demonstrated the system and lined up potential customers, the co-founders are working with outside advisors to raise $8 million in seed financing.

Path Robotics Inc., Cleveland, Ohio

Stage: Series A Funding

Most engineers develop a technology and then try to find a market for it. Brothers Andrew and Alex Lonsberry reverse-engineered the process.

The second-generation mechanical engineers started Path Robotics in 2014 as an engineering consultancy in Ohio. They already knew about robotics and machine learning. Their goal was to find customers and then build a system around their unanswered needs.

“You need to search and search to find that perfect market that exploits the technology you have,” Path CEO Andrew Lonsberry said. “It has to be big enough to get the interest of venture capitalists and [one that can] really grow.”

The brothers found their market when a customer said that small-to-medium-sized manufacturers faced a shortage of skilled welders, but robotic welding systems were geared for larger companies with a dedicated programming and support staff. He needed something smaller, cheaper, and easier to use.

Building two prototypes drew down Path’s cash. To raise venture capital, they queried former lab and classmates, other startups, and friends in Silicon Valley for ideas and introductions.

The answers were not encouraging.

“Early on, we were told that Silicon Valley venture capitalists like to fund startups in the Valley, with founders from the Valley, who’ve had experience working in the Valley,” Chief Technology Officer Alex Lonsberry said. “Anything hardware-related was too risky.”

The brothers ignored those warnings and travelled to California to meet with VCs who funded hardware companies. First, though, they practiced their pitch on friend and fellow mechanical engineer Lee Redden, co-founder of agriculture technology company Blue River Technology.

It was a good thing they did. He sharply critiqued their pitch. In response, they changed how they described their target market and their research so that it would be more meaningful to investors, the brothers said.

It worked.

Despite an “incredibly intimidating” introductory meeting with hardware VC Lemnos and their refusal to move to California, they scored a second meeting. The Lemnos partner then introduced them to 25 other firms.

Their efforts raised $2.5 million in seed round financing from lead investors Lemnos and Basis Set Ventures, another Valley VC, and six other firms.

Two months later—extremely unusual in the VC world—the brothers secured another $12.5 million in Series A funding through lead investor Drive Capital of Cleveland and Basis Set.

Critical to winning with the venture firms were those two working prototypes.

“To have a client that was at best making $20 million annually in revenue willing to shell out hundreds of thousands of dollars to us to make a prototype cell for them because they needed it so bad was a huge step in showing a product market fit,” said Alex.

Proterra Inc., Burlingame, Calif.

Stage: Series 7 Funding

Batteries and venture capital are powering Proterra’s zero-emissions electric buses on streets, highways, and around college campuses.

Electric buses were not on the agenda when founder Dale Hill, a mechanical engineer and a serial entrepreneur, bought a bus company in the early 2000s. It had a Federal Transit Administration contract to build low-emission compressed natural gas buses for Denver’s 16th Street Mall.

The vehicles impressed FTA, and in 2006 the agency offered Hill a grant to build a battery-powered bus prototype.

Hill used the money to reinvent the vehicle. Rather than convert a diesel bus to electric, Hill built his prototype from the ground up. This let him store the 18 ft. x 3.5 ft. x 0.6 ft. battery packs in the floors and between the tires, a safer and more efficient design, he said.

“The only new technology bus that had entered the market in the past 20 to 30 years was the bus we had built for Denver’s 16th Street Mall,” Hill said.

While grants and contracts could fund prototypes, Hill needed venture capital to build a business. He brought on a professional executive with experience attracting investors.

In 2010, Proterra nailed down its first commercial contract, ultimately selling 31 buses to Foothill Transit, a regional transit agency in Pomona, Calif.

Nine months later, the manufacturer used the contract and prototype to pitch investors. One of the nation’s top VCs, Silicon Valley’s Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, led a $30-million investment round.

As mass transportation turned greener across the country, Proterra’s customers grew to include cities, regional transit agencies, universities, and airports. Proterra raised an additional $420 million (excluding debt capital) from VCs between 2014 and 2018 in several funding rounds.

The company also added corporate investors, who helped it ramp up production. In fact, Germany’s Daimler, which makes buses as well as trucks and cars, co-led investors who poured $155 million into the company in 2018. The two companies announced future “synergies,” starting with jointly building electric school buses.

At the time, Proterra had sold more than 675 vehicles in the United States and Canada. It currently claims 60 percent of the North American electric transit market, and is expanding its Greenville, S.C., factory and building a new plant near Los Angeles.

“If you want to see your dream succeed then you have to determine what price you’re willing to pay,” Hill said.

Hill still retains his title of founder, but Kleiner Perkins controls the company and has moved its headquarters to just north of Silicon Valley.

Hill is OK with that. “So many good ideas get 90 percent to the goal line, and the person either runs out of money or gives up, and never gets to see their dream,” he said. “I’ve just been too stubborn to do that.”

Blue River Technology, Sunnyvale, Calif.

Stage: Acquired

Lee Redden and Jorge Heraud’s marriage of agricultural hardware and software became a VC success in 2017, when investors sold the business to Deere & Co. for $305 million for 10 times more than their investments.

The startup began when Redden and Heraud met in a Stanford University entrepreneurship class taught by Steve Blank, a serial entrepreneur and investor.

There, Redden’s mechanical engineering background in robotics and computer science meshed with Heraud’s 14 years at navigation systems leader Trimble, where he led the precision agriculture business unit.

They originally planned to build autonomous lawnmowers, but soon realized this was a dead end.

“The technology had not quite come of age, and it was very expensive,” Redden said.

So they pivoted. The result was See & Spray, a machine that uses computer vision to thin lettuce crops. Lettuce is intentionally overplanted, then thinned by hand. See & Spray does this automatically, detecting and spraying weaker plants with pesticides to prevent overcrowding.

Their instructor, Blank, was impressed enough to invest in seed funding. So did Ulu Ventures, a handful of angel investors, and friends. They raised $250,000, supplemented with substantial National Science Foundation grants.

The money let them rent space, buy equipment, and build a prototype, Redden said. But when they began looking for Series A funding, they met resistance.

“Most were pretty shy on funding things with hardware,” Redden said.

So they pivoted again, emphasizing the value of the data. Their smart system would understand what healthy lettuce—and perhaps other plants—looked like and use that information to thin rows or kill weeds. To minimize concerns, they told VCs that the hardware was “not as major a component” of the business.

Recommended for You: Requiem for Rethink Robotics

“They had a very clever business model,” Clint Korver, Ulu Ventures’ co-founder and managing director, said. “As opposed to selling the technology, they used the technology themselves and just sold the value. They were able to deliver it much better and cheaper than anyone else because of the clever technology they were using.”

In 2012, Khosla Ventures invested $3.1 million in Blue River. This enabled the pair to hire a team to build working prototypes that generated revenue.

With each funding round, Redden and Heraud delivered on key performance financial and technology benchmarks. This built investor confidence.

In 2014 a Series B round netted $10 million to commercialize See & Spray. In 2015, it raised $17 million, including funds from two agrochemical companies that might have wanted to partner with Blue River.

“They are not investing simply based on the financials, but on possible synergy between what you’re doing and what they’re doing,” Redden said.

To prepare for its next round of financing, Blue River pitched Deere & Co. as a potential strategic partner. The two companies found their visions of agriculture’s future aligned, and Redden and Heraud agreed to an acquisition. While they still lead the business they founded, Blue River is now a wholly owned subsidiary of Deere.

Carol Lawrence is a technology writer based in Los Angeles, Calif.