Building the Business Case for Industry 4.0

Building the Business Case for Industry 4.0

Digital engineering tools can add resiliency and agility for manufacturers of all sizes.

They say if you can’t fix it with duct tape, it’s not worth keeping. Rifino Valentine, owner of Valentine Distilling, a maker of spirits in Detroit, approached a challenge at his bottling operation with that attitude. When custom-shaped bottles created problems for the labeling machine, Valentine’s first impulse was to fix the problem by duct-taping guides to the equipment.

That didn’t work, so he took a chance on 3D printing. Using digital manufacturing technology instead of a few pieces of tape, he was able to improve his bottling operation.

Valentine’s experience is just one example of how companies of all sizes are digitally transforming their businesses using Industry 4.0 technologies they once feared were too expensive or complicated to consider. The shift marks a noticeable move beyond reluctance and exploration to implementation of varying degrees, despite the many roadblocks that still hinder adoption.

“This is the ‘hair on fire’ moment,” said Tom Kelly, executive director of Automation Alley, a Troy, Mich.-based I4.0 knowledge center that, among other initiatives, donated 300 high-quality Markforged 3D-printers to small- and medium-sized businesses like Valentine Distilling during the early days of the pandemic. “Everybody has to pay attention to I4.0 now.”

The digital technologies are generating more excitement than ever from the hundreds of manufacturers, academics, and vendors Kelly regularly speaks to, especially during the last few months. These folks are looking to learn more about the efficiencies, cost reductions, production and supply chain improvements, product customization, disruption mitigation, and other benefits the solutions deliver. They also want to hear about the challenges that impede adoption.

“It really is a groundswell,” Kelly said.

The tipping point toward greater Industry 4.0 adoption began during the pandemic when wireless and automated technologies enabled remote work and helped businesses operate with fewer onsite employees. The transformation has continued as manufacturers seek to leverage the improved resiliency, productivity, and agility the technologies delivered over the last three years. Lower acquisition costs, ease-of-use, clearer return on investment, a young digital-native workforce eager to explore new solutions, agnostic operating software, and managers less adverse to the risk of bringing on new solutions will continue to drive adoption.

“We’re at a 100 percent tipping point in I4.0 adoption,” said Justin Aglio, executive director of the Readiness Institute at Penn State University, which cultivates learning opportunities among communities, industry, and organizations. “It’s a combination of the increase of technology made available to us during the pandemic—the automation, the smart technologies, the connectivity of everything has advanced so much over the last two or three years.”

Becoming an ASME Member is Easier Than Ever

The global Industry 4.0 market, which stood at $131 billion in 2022, is projected to grow to roughly $377 billion by 2029, according to the international research firm Fortune Business Insights (FBI). Robotics, programmable logic controller automation, control room solutions, and other offerings, along with increased digitization and internet penetration, are driving the growth, the company reported. FBI also projected the global internet of things (IoT) market, which includes many of the foundational technologies that support I4.0, would increase from $385 billion in 2021 to $478 billion in 2022, and to about $2.5 trillion by 2029.

“During Covid people started talking about resiliency and agility and having production close to where your customers are,” Kelly said. “Resiliency and agility are top-of-mind of everybody I talk to in manufacturing.”

Those benefits were far from Valentine’s mind when Automation Alley offered him a free Markforged printer through its Project DIAMOnD (an acronym for Distributed Independent and Agile Manufacturing On Demand). The program, supported by local and federal government funding, started in 2020 to establish a domestic, connected manufacturing supply chain to create personal protective equipment (PPE) and other products. Valentine was reluctant to take the printer, thinking it would be too complicated and end up collecting dust. But there was no risk involved, so he accepted and was soon surprised at how easy it was to operate, thanks in part to online tutorials.

After completing his PPE commitments, Valentine quickly found a valuable use for the printer.

Valentine Distilling sells a line of whiskeys in distinctive bottles. The odd shape of those bottles can cause a problem: They can become stuck on the bottling line and cause the labeling machine to place the labels off-center. Looking for a quick fix, Valentine duct-taped some brushes to the machinery to better align the bottles. The brushes didn’t stay in place for long.

Using Section IX in conjunction with other construction codes? We have a course on that.

“It cost us a lot of time,” he said. Valentine, who has no experience as an engineer, spent about two-and-a-half hours using CAD software to design articulating arms to securely hold the brushes. The Markforged printer produced the components in about 10 hours. “The next morning, these things were ready to go,” he said.

The device still works perfectly. Valentine estimates it would have cost between $100 and $200 to build the arms from off-the-shelf parts or at least several weeks to receive them from the manufacture or maybe even longer during the pandemic—if similar parts even existed. “To be able to troubleshoot in real-time, not having to order a ton of parts, and being able to put it together quickly, saved us a lot of hassles,” he said. “The unknown is intimidating, but once you jump into it, it’s not as bad as you thought it would be.”

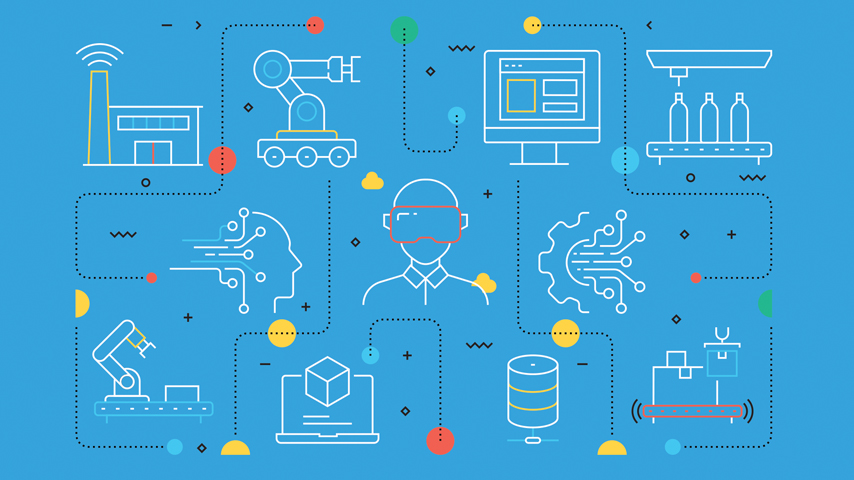

Additive manufacturing is just one of the suites of advanced engineering technologies that make up Industry 4.0. They all share some commonalities, however. For instance, they all rely on connectivity, data, and computing power, including sensors, cloud computing, blockchain, and other technologies associated with IoT. On a deeper level, many of the digital processes involve analytics and intelligence, including AI and machine learning.

There’s also a component of human-machine interaction, typically involving virtual and augmented reality, along with robotics and automation, two of the biggest drivers of I4.0 adoption.

“You’re now seeing a whole conversation around automation and robotics,” said Brian Anthony, the director of MIT’s Master of Engineering in Manufacturing program. “You hear that a lot of manufacturers are finally deciding to implement those because they can’t find the staff or they didn’t feel they needed to automate.”

Anthony is also a mechanical engineering professor and associate director of MIT.nano, who regularly consults with dozens of manufacturing managers and executives from SMBs and enterprise about I4.0 implementation. He says that technological maturity has helped spur interest by manufacturers into adopting Industry 4.0.

Despite the uptick, many companies remain reluctant to jump in the pool. According to several surveys, some of the main sticking points are proving return on investment and a shortage of skilled workers, followed by a lack of clarity on how to transition from legacy systems and support new ones, and data security.

One effort to dig deeper into the views of manufacturers was the Georgia Institute of Technology’s Georgia Manufacturing 4.0 Listening Day, a March 2022 workshop that included about 170 participants from 90 different types of companies.

“The number one thing they struggle with is how to develop ROI models,” said Aaron Stebner, an associate professor of mechanical engineering and materials science engineering at Georgia Tech, who helped coordinate the listening workshop and other I4.0 initiatives at the university. “The technical engineers may see the value in the technology, but translating that into a business case for the financial and other decision makers is the hardest thing to do.”

It can be more difficult to assess the value of I4.0 than for other types of capital expenditures because companies don’t always have the established methods and processes needed to collect and correlate key performance metrics and data. Besides, many vendors overhype the benefits of their I4.0 products, which can cast doubt over their effectiveness.

More on Manufacturing: 5 Popular Applications for Design for Additive Manufacturing

“It's not that easy to get the ROI as promised,” said Sid Verma, CTO and president Astec Digital, which focuses on providing digital solutions for the aggregate and roadbuilding industries. Verma, a mechanical engineer who has focused on implementing digital technologies for the last 20 years at Hitachi Vantara, Siemens Advanta, Deloitte Digital, and other companies, said the initial implementation of disruptive technologies is typically a “negative project,” something C-level execs don’t always understand or want to hear. It takes time for the solution to gain the efficiency, intelligence, and experience of the system it’s meant to replace.

“You’re paying extra costs for it while people are saying, ‘I can do a better job than this thing.’ The initial adoption, at least for the first few projects, are always negative ROI,” he said.

Given time, positive results can emerge. A global survey conducted in 2016 by PwC found that a $907-billion annual investment in I4.0 technology upgrades by industrial manufacturers was associated with $493 billion in revenue gains and $421 billion in cost and efficiency gains. The researchers identified annual revenue increases of 2.9 percent and cost reductions of 3.6 percent, according to Understanding the Impacts of Industry 4.0 on Manufacturing Organizations and Workers, a December 2021 report published by the Smart Factory Institute and University of Tennessee, both in Chattanooga.

While there are obvious and substantial costs to I4.0 implementations, the greater cost to manufacturers is inactivity, experts say. The cost of inaction (COI)—which translates to the failure to innovate production processes, products, and technology—leads to lost opportunity, the Smart Factory researchers wrote. COI among small manufacturers can also have a strong ripple effect, damaging the larger manufacturers they support. “Now and over the next few years is one of those times where failure to get (all manufacturers) on board with Industry 4.0 advancements will mean that everyone loses,” they wrote.

The key to creating reasonable and realistic ROI, experts say, is to begin with a small I4.0 implementation that targets a specific problem or complements an existing solution. Make sure it’s easy to operate and integrate with existing infrastructure.

Steve Michon, president and owner of Zero Tolerance, a plastic injection mold machine shop in Clinton Township, Mich., had one of those solutions in mind when he took on a Markforged printer after Automation Alley came knocking.

Editor's Choice: New 3D-printed Grippers for Short-term Manufacturing Runs

Michon wanted to build a claw-like device that could load brass cylinders about the width of a pencil into a mold for a tool the company made. In the past, he had used a MakerBot hobby-type printer for prototyping, but didn’t think its end product would be robust enough to withstand the heat of a 275 °F mold. He was skeptical the Markforged would work much better, even though it could print strong, carbon fiber-based material.

“I was expecting it not to work, to not hold up to the heat of the tool, and to wear out quickly,” he said. “To my surprise it lasted for a year before we had to touch it.”

The printed device shaved about eight seconds off each production cycle, and the company produces 50 percent more of the tools a day. Since then, Michon has purchased two new Markforged printers.

Zero Tolerance, a 12-person shop, has since established an additive manufacturing division that prints fixtures, tools, and proofs of concept for other companies and itself.

“3D printing accelerates the need to build more production tooling and fewer prototypes,” he said. “The speed to market has increased so much that I’m seeing more tool builds because of the 3D printing.”

The experience also led Michon to add a new molding press, EDM machine, and a five-axis CNC mill. He can operate and monitor all of the I4.0 machines online. Based on his own experience, he strongly advises companies to take the first step toward I4.0 adoption. If it’s the right tool for the right job, the ROI will follow.

“You really can’t look at the ROI until you’ve gotten involved in the technology,” he said. “It’s backward. If you don’t get into it, you’re going to be left behind. And when you get into it, you’re nervous because there doesn’t seem to be a return. And then your eyes are open, and you say, ‘My gosh, I can apply this to six other things that I wouldn’t have thought of.’ ”

Jeff O’Heir is a science and technology writer in Huntington, N.Y.

That didn’t work, so he took a chance on 3D printing. Using digital manufacturing technology instead of a few pieces of tape, he was able to improve his bottling operation.

Valentine’s experience is just one example of how companies of all sizes are digitally transforming their businesses using Industry 4.0 technologies they once feared were too expensive or complicated to consider. The shift marks a noticeable move beyond reluctance and exploration to implementation of varying degrees, despite the many roadblocks that still hinder adoption.

“This is the ‘hair on fire’ moment,” said Tom Kelly, executive director of Automation Alley, a Troy, Mich.-based I4.0 knowledge center that, among other initiatives, donated 300 high-quality Markforged 3D-printers to small- and medium-sized businesses like Valentine Distilling during the early days of the pandemic. “Everybody has to pay attention to I4.0 now.”

The digital technologies are generating more excitement than ever from the hundreds of manufacturers, academics, and vendors Kelly regularly speaks to, especially during the last few months. These folks are looking to learn more about the efficiencies, cost reductions, production and supply chain improvements, product customization, disruption mitigation, and other benefits the solutions deliver. They also want to hear about the challenges that impede adoption.

“It really is a groundswell,” Kelly said.

The tipping point toward greater Industry 4.0 adoption began during the pandemic when wireless and automated technologies enabled remote work and helped businesses operate with fewer onsite employees. The transformation has continued as manufacturers seek to leverage the improved resiliency, productivity, and agility the technologies delivered over the last three years. Lower acquisition costs, ease-of-use, clearer return on investment, a young digital-native workforce eager to explore new solutions, agnostic operating software, and managers less adverse to the risk of bringing on new solutions will continue to drive adoption.

“We’re at a 100 percent tipping point in I4.0 adoption,” said Justin Aglio, executive director of the Readiness Institute at Penn State University, which cultivates learning opportunities among communities, industry, and organizations. “It’s a combination of the increase of technology made available to us during the pandemic—the automation, the smart technologies, the connectivity of everything has advanced so much over the last two or three years.”

Becoming an ASME Member is Easier Than Ever

The global Industry 4.0 market, which stood at $131 billion in 2022, is projected to grow to roughly $377 billion by 2029, according to the international research firm Fortune Business Insights (FBI). Robotics, programmable logic controller automation, control room solutions, and other offerings, along with increased digitization and internet penetration, are driving the growth, the company reported. FBI also projected the global internet of things (IoT) market, which includes many of the foundational technologies that support I4.0, would increase from $385 billion in 2021 to $478 billion in 2022, and to about $2.5 trillion by 2029.

“During Covid people started talking about resiliency and agility and having production close to where your customers are,” Kelly said. “Resiliency and agility are top-of-mind of everybody I talk to in manufacturing.”

Machine solutions

Those benefits were far from Valentine’s mind when Automation Alley offered him a free Markforged printer through its Project DIAMOnD (an acronym for Distributed Independent and Agile Manufacturing On Demand). The program, supported by local and federal government funding, started in 2020 to establish a domestic, connected manufacturing supply chain to create personal protective equipment (PPE) and other products. Valentine was reluctant to take the printer, thinking it would be too complicated and end up collecting dust. But there was no risk involved, so he accepted and was soon surprised at how easy it was to operate, thanks in part to online tutorials.

After completing his PPE commitments, Valentine quickly found a valuable use for the printer.

Valentine Distilling sells a line of whiskeys in distinctive bottles. The odd shape of those bottles can cause a problem: They can become stuck on the bottling line and cause the labeling machine to place the labels off-center. Looking for a quick fix, Valentine duct-taped some brushes to the machinery to better align the bottles. The brushes didn’t stay in place for long.

Using Section IX in conjunction with other construction codes? We have a course on that.

“It cost us a lot of time,” he said. Valentine, who has no experience as an engineer, spent about two-and-a-half hours using CAD software to design articulating arms to securely hold the brushes. The Markforged printer produced the components in about 10 hours. “The next morning, these things were ready to go,” he said.

The device still works perfectly. Valentine estimates it would have cost between $100 and $200 to build the arms from off-the-shelf parts or at least several weeks to receive them from the manufacture or maybe even longer during the pandemic—if similar parts even existed. “To be able to troubleshoot in real-time, not having to order a ton of parts, and being able to put it together quickly, saved us a lot of hassles,” he said. “The unknown is intimidating, but once you jump into it, it’s not as bad as you thought it would be.”

Additive manufacturing is just one of the suites of advanced engineering technologies that make up Industry 4.0. They all share some commonalities, however. For instance, they all rely on connectivity, data, and computing power, including sensors, cloud computing, blockchain, and other technologies associated with IoT. On a deeper level, many of the digital processes involve analytics and intelligence, including AI and machine learning.

There’s also a component of human-machine interaction, typically involving virtual and augmented reality, along with robotics and automation, two of the biggest drivers of I4.0 adoption.

“You’re now seeing a whole conversation around automation and robotics,” said Brian Anthony, the director of MIT’s Master of Engineering in Manufacturing program. “You hear that a lot of manufacturers are finally deciding to implement those because they can’t find the staff or they didn’t feel they needed to automate.”

Anthony is also a mechanical engineering professor and associate director of MIT.nano, who regularly consults with dozens of manufacturing managers and executives from SMBs and enterprise about I4.0 implementation. He says that technological maturity has helped spur interest by manufacturers into adopting Industry 4.0.

Barriers to entry

Despite the uptick, many companies remain reluctant to jump in the pool. According to several surveys, some of the main sticking points are proving return on investment and a shortage of skilled workers, followed by a lack of clarity on how to transition from legacy systems and support new ones, and data security.

One effort to dig deeper into the views of manufacturers was the Georgia Institute of Technology’s Georgia Manufacturing 4.0 Listening Day, a March 2022 workshop that included about 170 participants from 90 different types of companies.

“The number one thing they struggle with is how to develop ROI models,” said Aaron Stebner, an associate professor of mechanical engineering and materials science engineering at Georgia Tech, who helped coordinate the listening workshop and other I4.0 initiatives at the university. “The technical engineers may see the value in the technology, but translating that into a business case for the financial and other decision makers is the hardest thing to do.”

It can be more difficult to assess the value of I4.0 than for other types of capital expenditures because companies don’t always have the established methods and processes needed to collect and correlate key performance metrics and data. Besides, many vendors overhype the benefits of their I4.0 products, which can cast doubt over their effectiveness.

More on Manufacturing: 5 Popular Applications for Design for Additive Manufacturing

“It's not that easy to get the ROI as promised,” said Sid Verma, CTO and president Astec Digital, which focuses on providing digital solutions for the aggregate and roadbuilding industries. Verma, a mechanical engineer who has focused on implementing digital technologies for the last 20 years at Hitachi Vantara, Siemens Advanta, Deloitte Digital, and other companies, said the initial implementation of disruptive technologies is typically a “negative project,” something C-level execs don’t always understand or want to hear. It takes time for the solution to gain the efficiency, intelligence, and experience of the system it’s meant to replace.

“You’re paying extra costs for it while people are saying, ‘I can do a better job than this thing.’ The initial adoption, at least for the first few projects, are always negative ROI,” he said.

ROI vs. COI

Given time, positive results can emerge. A global survey conducted in 2016 by PwC found that a $907-billion annual investment in I4.0 technology upgrades by industrial manufacturers was associated with $493 billion in revenue gains and $421 billion in cost and efficiency gains. The researchers identified annual revenue increases of 2.9 percent and cost reductions of 3.6 percent, according to Understanding the Impacts of Industry 4.0 on Manufacturing Organizations and Workers, a December 2021 report published by the Smart Factory Institute and University of Tennessee, both in Chattanooga.

While there are obvious and substantial costs to I4.0 implementations, the greater cost to manufacturers is inactivity, experts say. The cost of inaction (COI)—which translates to the failure to innovate production processes, products, and technology—leads to lost opportunity, the Smart Factory researchers wrote. COI among small manufacturers can also have a strong ripple effect, damaging the larger manufacturers they support. “Now and over the next few years is one of those times where failure to get (all manufacturers) on board with Industry 4.0 advancements will mean that everyone loses,” they wrote.

The key to creating reasonable and realistic ROI, experts say, is to begin with a small I4.0 implementation that targets a specific problem or complements an existing solution. Make sure it’s easy to operate and integrate with existing infrastructure.

Steve Michon, president and owner of Zero Tolerance, a plastic injection mold machine shop in Clinton Township, Mich., had one of those solutions in mind when he took on a Markforged printer after Automation Alley came knocking.

Editor's Choice: New 3D-printed Grippers for Short-term Manufacturing Runs

Michon wanted to build a claw-like device that could load brass cylinders about the width of a pencil into a mold for a tool the company made. In the past, he had used a MakerBot hobby-type printer for prototyping, but didn’t think its end product would be robust enough to withstand the heat of a 275 °F mold. He was skeptical the Markforged would work much better, even though it could print strong, carbon fiber-based material.

“I was expecting it not to work, to not hold up to the heat of the tool, and to wear out quickly,” he said. “To my surprise it lasted for a year before we had to touch it.”

The printed device shaved about eight seconds off each production cycle, and the company produces 50 percent more of the tools a day. Since then, Michon has purchased two new Markforged printers.

Zero Tolerance, a 12-person shop, has since established an additive manufacturing division that prints fixtures, tools, and proofs of concept for other companies and itself.

“3D printing accelerates the need to build more production tooling and fewer prototypes,” he said. “The speed to market has increased so much that I’m seeing more tool builds because of the 3D printing.”

The experience also led Michon to add a new molding press, EDM machine, and a five-axis CNC mill. He can operate and monitor all of the I4.0 machines online. Based on his own experience, he strongly advises companies to take the first step toward I4.0 adoption. If it’s the right tool for the right job, the ROI will follow.

“You really can’t look at the ROI until you’ve gotten involved in the technology,” he said. “It’s backward. If you don’t get into it, you’re going to be left behind. And when you get into it, you’re nervous because there doesn’t seem to be a return. And then your eyes are open, and you say, ‘My gosh, I can apply this to six other things that I wouldn’t have thought of.’ ”

Jeff O’Heir is a science and technology writer in Huntington, N.Y.