Cutting Edge Culinary Mechanics

Cutting Edge Culinary Mechanics

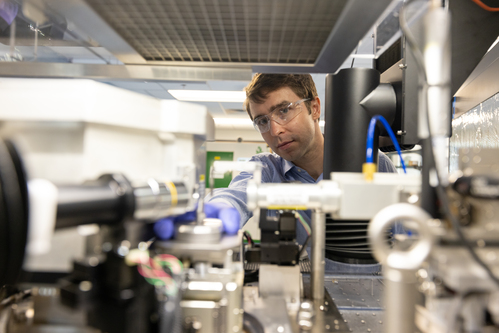

Amaranth is one of the grains that professor Philip LeDuc is utilizing in his "culinary mechanics" research.

The amaranth plant grows as wildly in Africa and South America as poppies do in western California. Amaranth, known as pigweed in American parlance, grows everywhere – between rocks, on scrubby patches of arid land, in open fields – and it is more a scorn and nuisance to local villagers than anything of real value. But to Phillip LeDuc, a professor of mechanical engineering at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, amaranth is more than a useless weed. It is a precious commodity that can be processed into a nutritional and palatable foodstuff to help alleviate hunger in areas where the plant grows.

LeDuc is what you might call a creator of food, however, not in the traditional sense. He is not formally trained in the culinary arts. He is not involved in genetically modified crops, nor does he tinker in molecular gastronomy or any of the other new methods of food preparation practiced in top cooking schools.

LeDuc is in the business of culinary mechanics, which uses the fundamentals of mechanical engineering to alter the structure of vegetables, meats, condiments, and other types of foods to produce taste and nutritional value. He recently has been developing the research in collaboration with a Ph.D. student, Mary Beth Wilson.

“The application of mechanical engineering in food preparation dates back centuries to when people first started using tools like the mortar and pestle,” said LeDuc, who last year introduced a course on culinary mechanics at Carnegie Mellon, the first of its kind in the world. “Our approach involves thinking about food by scientifically analyzing how mechanics affects taste and nutrition.”

Engineering New Foods

According to LeDuc, the toughness, texture, and consistency of food can be altered through controlled mechanics such as cutting, chopping, and mixing. He and Wilson use various laboratory techniques to study the cellular and molecular micro-architecture of certain foods and carry out experiments to assess the mechanical interventions that could alter the microstructure to produce differences in taste, texture, and nutrition.

In the case of amaranth, LeDuc and Wilson have applied a chopping and grinding process to convert a tough, leafy green into an edible food having the texture, palatability, and vitamin content of jarred baby food.

The newfangled amaranth, says LeDuc, could fill a lot of tummies in poverty-stricken villages in Africa and South America where the local populations subsist on meager allowances of wholesome, vitamin-rich foods. There is a decided humanitarian component to LeDuc’s activity, which prompted the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which allocates hundreds of millions of dollars a year to research geared toward increasing global health and reducing poverty, to fund the culinary mechanics idea an amount of $100,000.

Besides helping to alleviate global hunger, another focus of culinary mechanics is obesity. In one recent classroom project, students broke down avocado into a texture suitable for a cheesecake filling, replacing high-calorie cream cheese. Nuts have also been tried for cheesecake filling.

And commercial food producers are beginning to take an interest in culinary mechanics. In fact, the program at Carnegie Mellon received footing when representatives of a ketchup maker called on LeDuc to discuss a project. “The company understood that mechanical engineering principles and concepts play a strong role in innovations in food texture, taste and nutrition, as well as packaging and delivery,” said LeDuc. “Early on, the company explored applications of cell mechanics in ketchup, seeking best practices to mash tomatoes and bottle the product.”

LeDuc is also working to raise awareness of culinary mechanics in restaurants and culinary schools, which in recent years have been exploring synergies between the sciences – mainly chemistry – and food preparation. The famous Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, NY, now teaches the modernist cuisine, putting its students through courses in precision temperature cooking, flavor science, and molecular gastronomy. Aspiring chefs at the CIA are taught tips for preserving truffles in carbon dioxide and making strawberry sorbet using liquid nitrogen.

“Scientific principles have always informed the culinary arts, however, the food industry has focused heavily on only the chemistry” said LeDuc. “Culinary mechanics investigates how mechanics influences the chemistry.”

Pancakes on the Go

LeDuc’s students recently demonstrated the interdisciplinary union of chemistry and mechanical engineering in food preparation, creating a novel type of pancake. Fondly called “pancakes on the go,” but resembling nothing like standard flapjacks, the students created bite-sized pancakes and placed encapsulated syrup in the center of the morsels. By design, the capsules rupture and the syrup is released when the pancake bites are chewed.

“What appears at a glance to be a simple invention is actually the end result of in-depth research and experimentation in the mechanical properties of a spherification,” said LeDuc. “For pancakes on the go, we had to understand a range of mechanical and chemical processes to be sure that the materials created for holding the syrup would perform.”

While it is not certain that consumers will take to the new-style pancakes, LeDuc and his students are demonstrating that novel mechanics-based approaches can be integrated to create new food products.

“Culinary mechanics has massive potential in cuisine and also in the fight against obesity and global hunger,” said LeDuc. “It is my goal to advance the research and create products that contribute toward this end.”

The application of mechanical engineering in food preparation dates back centuries to when people first started using tools like the mortar and pestle.Prof. Phillip LeDuc, Carnegie Mellon University