Tapping Trash for Landfill Energy

Tapping Trash for Landfill Energy

Aerial photo of the Puente Hill Landfill, the largest landfill in the United States. Image: Britta Gustafson / Wikimedia Commons

Methane is no good for the atmosphere. In terms of its contribution to climate change, it’s about 25 times worse than carbon dioxide. But, of course, if captured, the gas can be put to pretty good use, effectively killing the energy-need bird and the greenhouse-gas bird, with a single stone.

Such a stone makes a nice sized dent when hurled at our mountains of garbage. Somewhere near a third of the methane produced by humans in the U.S. comes from landfill. If you can get ahold of it before it hits the atmosphere, you’ve done the environment a service and produced a little energy on the way.

That’s just what the Environmental Protection Agency’s Landfill Methane Outreach Program (LMOP for short) has been advocating since 1994. “In the last 20 years we have been very active in educating the public and communities,” says Swarupa Ganguli, the LMOP Team Lead. That education has taken the form of visits to landfills, webinars, seminars, and conferences—and it’s been very effective. When the program was first conceived there were only 130 landfills converting their gas. Now there are 645 and a good 440 that are ripe for exploitation.

But that exploitation is not quite as straightforward as tapping the earth for natural gas. The gas produced by the organic material breaking down in a landfill is about 45 to 50 percent CO2, 50 to 55 percent methane, one percent miscellaneous organic compounds and trace amounts of inorganic compounds. It’s a “medium BTU” gas, meaning that it has about half the heating value of natural gas. The long and short of it is that it has to be treated.

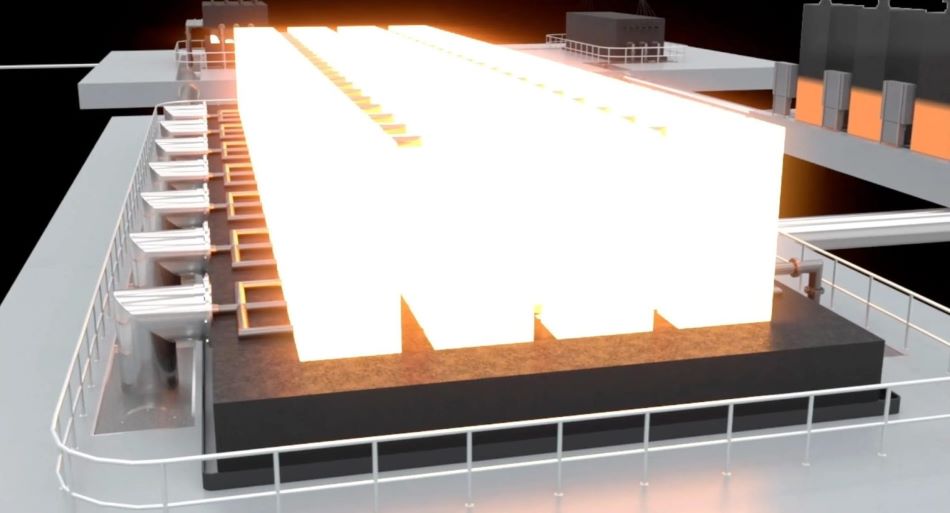

The simple version, dewatering, makes a product suited to internal combustion engines or for boilers. For something more complex, such as a natural gas substitute, chemical scrubbing is needed (though with current natural gas prices where they are, such a process wouldn’t make much economic sense). Most landfills produce something like 9,000 cubic feet a day. California’s Puente Hills landfill is the largest in the country and the largest producer of gas, in the 50-plus megawatt range.

These numbers could, in theory, be upped a good deal. Few landfills operate anywhere near an ideal “capture efficiency.” Gas is lost through seepage in the wells and cracks in the landfill covering. But there are new types of covers that can oxidize the methane to “prevent the fugitive emissions,” says Ganguli. Another option is to capture gas earlier. Currently, landfill operations must wait 30 months before they begin harvesting gas. But landfills can begin producing gas in the six to eight month range and there is evidence that having the wells in place earlier is beneficial. Advance leachate management systems can minimize the flooding of leachate into the wells. There are also bioreactor landfills, where leachate is injected into the landfills to increase moisture and, ultimately, gas production.

The question of whether a horizontal or vertical well is more efficient continues to be debated within the industry. But if a well is capturing gas in a portion of the landfill that is still active, it needs to be horizontal.

Though it’s all in the name of the environment, if every municipality made better use of their biodegradables, landfills would actually produce less energy. “In an ideal world you would be diverting your organics and using them for composting and aerobic digestion,” says Ganguli. And, in fact, 21 states have banned the sending of organic material to landfill. But the laws and the programs to handle compostable waste are all new, and their impact on landfill gases won’t likely be seen anytime soon.

Until composting utopia hits, landfills will continue to keep the gas they produce out of the air by capturing it as efficiently as possible. “The market is mature,” says Ganguli, “and there is a robust number of projects out there.”

Michael Abrams is an independent writer.

Learn more about the latest energy technologies atASME’s Power and Energy Conference.

In an ideal world you would be diverting your organics and using them for composting and aerobic digestion.Swarupa Ganguli, LMOP Team Lead